Latest

The Evolution of Bass Ramps

GWB35BKF Finger Ramp

There’s no doubt that for the last eight decades the Electric Bass Guitar has been the musical instrument with the most rapid evolution. It has evolved in many ways including, musically, functionally and technologically.

Within those technological aspects, over the last 27 years we’ve seen the appearance and evolution of a very simple device for the electric bass, the bass ramp. We’ve analyzed that evolution and made an attempt to establish just how it happened and who have been the players responsible for bringing this to the forefront.

The ‘Bass Ramp’, in general terms is a flat surface generally made out of wood that goes below the strings, which prevents the right hand fingers (left hand fingers for those playing left handed) from digging in too hard, providing the player a similar sensation to the feel they get when they play over the bass pickups, but spread over a much larger surface.

We have interviewed the five main bassists responsible for the evolution, who happen to be some of the finest bass players in the world. Included are Gary Grainger, Gary Willis, Igor Saavedra, Matt Garrison and Damian Erskine. Their invaluable collaboration with BMM allowed us to get all the information we needed to really dig deep and offer a serious analysis on this simple device.

After putting all the puzzle pieces in order, it seemed very clear to us that two bass ramp styles made a real difference, becoming the most recognizable and differentiated ramps that we now see everywhere, and are being installed in more basses every year. Depending on the different types, some of these ramps have slightly different names, mostly defined by their creators.

These two different bass ramps evolved sequentially and were created out of necessity by the five players. With all the information collected, we could also establish that the origin of a bass ramp was the bass pickups themselves, which gave the players that special ‘comfort feeling’; later they tried to replicate this feeling in a more specialized and dedicated way.

These are the two main bass ramp types that changed bass history, as well as the inventors behind them…

The Glued Ramp Located Beside or In Between the Pickups

This is the Genesis of the bass ramp and the title says it all. It’s a piece of wood that matches the shape of the pickups, that can either go between the neck and the neck pickup, between the neck pickup and the bridge pickup, between the bridge pickup and the bridge, or all of the options just mentioned at the same time. It generally goes attached with double-sided tape or just glued on.

We could establish that probably the first player to follow this path was Gary Willis. He started by putting together two bridge pickups in 1981 and then decided to find a bass with separated pickups and install a piece of wood in between them, probably around the beginning of 1986. We noticed that in videos prior to 1985, Willis appears playing with a Fender shaped bass with no ramp on it yet. We found a video of him playing with the Wayne Shorter Quartet on Sunday, July 13, 1996 at the North Sea Jazz Festival, where he’s playing a Tobias Bass loaded with what we think should be the very first bass ramp to be seen live; this famous ramp is known now by any dedicated bass player as, “The Willis Ramp”.

On the same path and probably coming with the same idea, without necessarily having seen Gary Willis ramp (as video was not as prominent as it is today), we assume that Gary Grainger started to use the same piece of wood in between two Soapbar Pickups around the second half of 1986 or beginning of 1987, based on the information he shared with us. We found a video of him playing live with the John Scofield Quartet in July 1986 at the Umbria Jazz Festival, where he can still be seen playing with his famous Musicman, where no ramp is attached. The first video recording that we could find where he can be seen using a bass ramp, loading his 5-string Ken Smith, was on a 1992 DCI Dennis Chambers instructional video, but as we mentioned before, he told us that he started to experiment with his first bass ramps around 1986 – 1987.

Finally, we include Matthew Garrison on this path, a highly distinguished and dedicated bass ramp user, who was the first to bring the concept to Fodera. Matt told us that he started to use this type of ramp right after trying the Gary Willis Signature Bass, loaded with the Willis Ramp at the 1994 NAMM Show.

The Adjustable Height Ramp That Contains the Pickups

Like any invention in the history of humanity it was clear that the first ramps had a lot of space to evolve. Also, in this case the title says it all; a ramp that has screws on the four corners, so as to adjust the height and at the same time contain the pickups inside so the player can play beside or over them if he wants, still keeping the same ramp feel.

South American Bassist Igor Saavedra came up with an idea almost 20 years ago, an adjustable height bass ramp that contained the pickups, instead of being placed on their sides, glued to the body of the bass. He came up with the idea after having a conversation with Gary Willis in Chile back in 1992. Igor shared, “The first prototypes were done by himself back in 1995, but the first official ‘MicRamp’, was commissioned by Luthier Alfonso Iturra in late 1998 and finished in 1999, loading a 6-string bass that he was handcrafting for me.” Igor can be seen everywhere playing with his MicRamp in many videos and footage from 1999 and up.

Happening during the same timeframe in the United States, Damian Erskine developed a very similar bass ramp, which he called the, “Rampbar” and was made for him by the great Luthier, Pete Skjold around 2010.

All of the above was extracted from the actual interviews that we did with these five well-known bassists and we have now the pleasure to leave you with the actual interviews, so you can get the story first hand. We hope you enjoy their stories as much as we did.

1) What was the exact year you did your first ramp and the reasons that lead you to do it?

It was somewhere around 1981 and it wasn’t actually a ramp yet. I had these DiMarzio pickups and I put two of them side-by-side in the rear pickup position. They had threaded pole pieces that you could raise or lower so when I raised the middle ones the sharp threads were cutting my fingers. So I got a hole-puncher and added layers of tape to protect my fingers and also was able to shape the surface so that it had equal string to pickup spacing. So it had kind of a contour – a ramp – if you will. The contour gave it a very consistent feel for my three finger technique.

I wasn’t thrilled with the side-by-side pickup sound so on my next bass I attached a contoured piece of wood next to the pickup so I could have that same sensation of a consistent playing surface under my three fingers.

2) Inventions in history are always based on a previous invention, where did your idea came from?

You can sort of tell that it wasn’t based on anything previous, I was just originally trying to prevent losing skin!

3) With your first ramp… did you do it yourself or ask a Luthier?

I always did them myself and I’ve probably made over 200 for people throughout the years. When I finally started having companies build basses for me then it became part of the design.

4) Have you made any improvements to it throughout the years?

When Ibanez released the first version back in 1999, we weren’t sure about the ramp’s acceptance so we made it removable. It was attached with double sided tape so it was adjustable but if someone didn’t want it, it could be removed. As time passed and ramps became more accepted, we put screws to make it adjustable.

5) What are the technical benefits you got from your ramp, did it change the way you play?

The technical benefits are numerous. First, it eliminates digging in too hard and hearing that ugly sound of the string banging against the fingerboard. Second, it allows you to get warmer tones from playing further away from the bridge while still giving that consistent feel. Third, of course, is that it makes the perfect thumb rest. Fourth, since it reinforces the concept of playing lighter (you compensate by turning up) it will allow more fundamental and air throughout the duration of a note, instead of thinning out right away after the attack from playing too hard. Finally, if used and set up properly, it will allow you to discover a broader range of dynamics while getting a better tone.

The first version just gave a sense of security to my three fingers, since that was all it would accommodate. But as I gradually extended it, eventually eliminating the front pickup and reaching all the way to the neck, I discovered how the benefits of playing closer to the neck for certain tones. So yes, if a ramp is adjusted properly it should change the way you play.

6) Have you any legal patents on your invention?

It’s not patented. And it doesn’t make sense to patent it unless I wanted to become a patent troll and just punish people for using it. It wouldn’t make a profit since you can’t really define its dimensions because of all the different pickup configurations out there. Plus before it’s installed, the pickup height and action has to be set. So it kind of has to be fabricated bass-by-bass.

7) What are your thoughts when you see your ramp being used by so many bassists nowadays?

It’s great to see. I can’t take exclusive credit for inventing it since I’ve heard of other people developing it independent of me, but I’m glad to see players developing an awareness of dynamics and touch and using the ramp to help with that.

Visit online at garywillis.com

1) What was the exact year you did your first ramp and the reasons that lead you to do it?

It was around the same time I started playing with John Scofield… so that would be about 1986, 87.

2) Inventions in history are always based on a previous invention, where did your idea came from?

The first bass I had and learned how to play was a Fender Precision with a Humbucking pick-up on it. Later, I bought a Music Man Sting Ray, which also had the big pick-up on it.

When I picked up other bases, I did not like how it felt when I played finger style….then….I realized that I was using the big Humbucking pick-up on the basses as a way of stopping my fingers from going too far down in the strings when I played. So, I had a piece of wood placed where I like to play with my fingers on my other basses and that made it feel right to me.

At that point, I bought a Ken Smith five and I had the block of wood glued to the bass. It felt great. Then, I started working with Paul Reed Smith on building a bass for me. The bass turned out to be amazing, so now I have a signature bass line with PRS and we offer the 4 and 5 string basses with or with-out the ramp.

3) With your first ramp… did you do it yourself or ask a Luthier?

I had “John Warden” (Guitar & Bass builder and repair man) cut and place the ramps on for me at that time. Now PRS does it for my basses.

4) Have you made any improvements to it throughout the years?

The only improvement that I made was to have little trenches dug out on the ramps to allow the strings to vibrate on my basses.

5) What are the technical benefits you got from your ramp, did it change the way you play?

It allows me to play with a lighter touch which I think helps me avoid some hand tension problems that comes sometimes when we play.

6) Have you any legal patents on your invention?

No, I have no patents on the ramp.

7) What are your thoughts when you see your ramp being used by so many bassists nowadays?

I think it is great to see so many players that think the same way that I do……cool.

Find online: prsguitars.com/artists/profile/gary_grainger

1) What was the exact year you did your first ramp and the reasons that lead you to do it?

I was lucky to meet Gary Willis on his visit to Chile with Tribal Tech back in 1992. I lent him my amplifier for the concert, and that allowed me to be in the theater for the sound check. I was intrigued by that piece of wood his bass had, so I asked him everything I could about it. He was very kind to explain to me all of the details and the benefits, and when I grabbed the bass I just loved the sensation. I almost immediately asked him if it could be height adjustable and if there were pickups underneath the ramp. He told me that it wasn’t height adjustable and that there were not any pickups underneath, adding that he was quite comfortable with the way his ramp was but encouraged me to investigate more if I felt it necessary. In fact I felt it very necessary and kept thinking about that idea until 1995 when I did my first prototype and a few more between 1995 and 1998. My first official MicRamp, which was the name I gave it, was inserted as a structural component of a 6-string bass that I commissioned to do with the well-known Luthier and former sponsor Alfonso Iturra. He started to build that in late 1998 and finished it in 1999.

2) Inventions in history are always based on a previous invention, where did your idea came from?

There’s no doubt about it for me… my MicRamp is a direct descendant of the Willis Ramp. It exists because of it and also because of Gary Willis’ encouragement to go for it. I thank him for being so kind with me back in those years when I was just starting to play bass, because I’m pretty sure I must have overwhelmed him with so many questions that day.

3) With your first ramp… did you do it yourself or ask a Luthier?

The first ones I did them myself, and eventually commissioned Alfonso Iturra, as a master Luthier, I knew the ramp was going to be really well made, which it was.

4) Have you made any improvements to it throughout the years?

Oh sure… there were 3 prototype versions between 1995 and 1998, then two more versions made by Alfonso Iturra for a 6-string and my first 8-string bass Octavius 1.0. The 6.0 Version was made by the great Chilean Luthier Claudio González, loading my Octavius 2.0, which is my most famous bass untill now. My actual official ramp was made by Oscar Prat loading my new PRAT Signature Bass and is the 7.0 version, which in fact is absolutely outstanding. It is good to point out that one of the characteristics that define the MicRamp is that the screws (Allen) are inserted from behind the bass body, and always have, so they are not noticeable from the front. Also the MicRamp has always been loaded with springs around those screws, for keeping the height stable.

5) What are the technical benefits you got from your ramp, did it change the way you play?

There are plenty. First of all the height adjustment allows you to follow any change you want to make on the bass (action) or in your playing (grip & touch), so being in that comfort zone, your playing will be as soft as you want it to be. Also the grip on the strings will be super-steady with the inherent dynamics and stability benefits, along with a relaxed hand position to rest over the ramp that will be able to achieve much more cleanness and speed if needed. Second, having the pickups inserted on the ramp allows you to play right over where the sound is being captured, and due to the fact that the MicRamp is larger than the pickups you can also play in between and on the sides of the pickups if you want. Third, having an absolutely flat surface with no screws coming from the front brings you a lot of “Peace of Mind,” so no matter where you are playing you will never scratch your fingertips with the head of a screw or the edge of their hole. Fourth, sound is not affected at all. Fifth, it just looks so beautiful without the screws in the front.

6) Have you any legal patents on your invention?

No, and do not have any intention. My idea belongs now to the world’s bass community and I don’t even imagine myself wasting my time in lawyers and crazy paperwork for something like that. I know I was the first to come up with the idea and that’s enough for me and the bass community supports that fact. I’m aware that many years later there have been a couple of great bassists that came to the same conclusion without necessarily knowing about my MicRamp and that’s absolutely fair.

7) What are your thoughts when you see your ramp being used by so many bassists nowadays?

It feels really great… it’s a sensation of giving and sharing something that has come out of your life and your experiences, something very similar to when I teach, but just applied on a different context. Each time I see a bass loaded with a MicRamp I feel that a little piece of me is living on it… the screws of those ramps are usually inserted from the front though, so if you want to go the “Original Style” ask your Luthier to insert them from the rear, it just looks much better IMHO (smile).

Visit online at bajoigorsaavedra.cl

1) What was the exact year you did your first ramp and the reasons that lead you to do it?

1994. I had played Gary Willis’s signature bass during that years NAMM and knew immediately it would help me develop the four-finger technique I was just developing at the time. Everything just fell into place after I had Fodera install the ramp on my signature model. They were a little puzzled at the request since no one had ever asked for a ramp to be installed on one of their basses, but shortly thereafter it all made sense to all of us.

2) Inventions in history are always based on a previous invention, where did your idea came from?

I didn’t invent anything in this department. Apparently Gary Grainger had a ramp installed on his bass prior to Gary Willis as Grainger points out, so perhaps he’s the very first bass player to have navigated this new territory. He would be a great artist to talk to regarding this topic. However I only encountered the use of a ramp for the first time on Gary Willis’s bass.

3) With your first ramp… did you do it yourself or ask a Luthier?

I asked the gang at Fodera.

4) Have you made any improvements to it throughout the years?

Sure. We tried different woods, different positioning, different options in terms of being able to take it off if necessary. Also we tried different ways of adjusting the individual levels of the four corners of the ramp.

5) What are the technical benefits you got from your ramp, did it change the way you play?

Absolutely changed my playing forever. I could all of the sudden accomplish certain technical ideas that were just too tricky without the ramp. I’m still finding new uses for the ramp. The only downside is of course to really do what I do technically I can only do it with a ramp installed. Of course I can take care of my bass playing basics without, however my language is fully built around the use of a ramp.

6) What are your thoughts when you see ramps being used by so many bassists nowadays?

I think it’s magnificent how such a simple piece of technology makes sense to so many bass players around the world. It’s not just a series of people imitating an action for the sake of imitation. There are true benefits to the concept and it’s amazing how wide spread it is. We must all give thanks to Gary Grainger and Gary Willis as the true innovators regarding this idea.

Visit online at garrisonjazz.com

1) What was the year you did your first ramp and the reasons that lead you to do it?

I believe that I installed my first ramp on my Modulus 6 string back in 1999 or so. I was always one to play over the pickups and I was intrigued by the idea of broadening my ‘comfort zone’ in between the bridge and the neck. My current ramp style was developed in conjunction with Pete Skjold somewhere around 2010 or 2011. The ramp I have on my Skjold basses is a hybrid. We’ve combined the pickup moulds with the ramp so we have, essentially, two soap-bar pickups incorporated into an oversized pickup mould (which matches the contour of the fretboard perfectly).

2) Inventions in history are always based on a previous invention, where did your idea came from?

Although I can’t remember where I first saw or heard of the idea for any kind of ramp, it was likely by checking out Gary Willis. I was always one to tinker with everything though. I had an obsessive need to personalize my gear (not visually, but functionally). I loved evaluating HOW I played and then trying to make the instrument better assist me in any way.

3) With your first ramp… did you do it yourself or ask a Luthier?

When building my first wooden ramps, I actually just scoured the waste pile of a furniture maker until I found something that looked nice and was something close to the right size. I then made some cuts, sanded it down and used double sided tape to attach it. I was lucky in as much as the Modulus had both flat pickups and a flat fingerboard, so I didn’t have to worry about radiusing the ramp at all. I had to have a Luthier install some later ramps on basses that had radiused finger boards. I also had to start making sure that I always had pickups that matched the radius of my neck. It drove me crazy for about a year when I had a bass with a radiused board, radiused ramp and flat pickups! Had to get those switched out… kicked my ocd into hyper drive! Lol

Now, my Skjold ramps can only be made by Pete Skjold. Also, the pickups are custom wound so he’s really the guy who does most everything (beyond basic setup and tweaking) on my basses.

4) Have you made any improvements to it throughout the years?

Well, by now Pete Skjold and I have come up with our own pickup moulds that incorporate the ramp. Most people assume that it is just a cover but the pickups are wired directly into that large mold creating one smooth giant looking pickup that serves as the ramp. We explored this because we wanted one smooth surface with no edges but weren’t so much into the idea of just plopping a cover over the pickups. I couldn’t be happier with the results!

5) What are the technical benefits you got from your ramp, did it change the way you play?

Initially I liked ramps because they kept me from digging in too hard. It forced me to play a little lighter as well as evening out my right hand technique. Now, I actually set the pickup/ramp a bit lower than I used to because I like to have more dynamic range available to me with my right hand, but it still feels like home. I like feeling something under my fingers when I play. I have also been using my thumb (not slapping, though… just finger style) quite a bit over the past few years and the ramp has really helped me to maintain control over my strikes, keeping them even across my 3 plucking fingers.

6) Have you any legal patents on your invention?

No, although Pete Skjold may have some on certain aspects of his design (not really sure, though!).

7) What are your thoughts when you see ramps being used by so many bassists nowadays?

I’m all for innovation. It helps to facilitate a certain style of playing. I always hope that all players explore the instrument fully and decide what their voice and preferred tactile experience really is on the instrument before they just do what X or Y player is doing. Everything I’ve tweaked on my basses (chambering, my Duo-Strap with Gruv Gear, ramp style pickup) has come about through the exploration of my style and my voice. I think it’s important to fully explore your instrument, your musical voice and then work to bring the two together in harmony.

Visit online at damianerskine.com

Bass Videos

Interview With Bassist Erick “Jesus” Coomes

Bassist Erick “Jesus” Coomes…

It is always great to meet a super busy bassist who simply exudes a love for music and his instrument. Erick “Jesus” Coomes fits this description exactly. Hailing from Southern California, “Jesus” co-founded and plays bass for Lettuce and has found his groove playing with numerous other musicians.

Join us as we hear of his musical journey, how he gets his sound, his ongoing projects, and his plans for the future.

Photo, Bob Forte

Featured Videos

Visit Online

www.lettucefunk.com

IG @jesuscsuperstar

FB@jesuscoomes

FB @lettucefunk

Bass Videos

Working-Class Zeros: Episode #2 – Financial Elements of Working Musicians

Working-Class Zeros: Episode #2 – Financial Elements of Working Musicians

“These stories from the front are with real-life, day-to-day musicians who deal with work life and gigging and how they make it work out. Each month, topics may include… the kind of gigs you get, the money, dealing with less-than-ideal rooms, as well as the gear you need to get the job done… and the list goes on from there.” – Steve the Bass Guy and Shawn Cav

Latest

This Week’s Top 10 Basses on Instagram

Check out our top 10 favorite basses on Instagram this week…

Click to follow Bass Musician on Instagram @bassmusicianmag

FEATURED @foderaguitars @overwaterbasses @mgbassguitars @bqwbassguitar @marleaux_bassguitars @sugi_guitars @mikelullcustomguitars @ramabass.ok @chris_seldon_guitars @gullone.bajos

Bass CDs

New Album: Jake Leckie, Planter of Seeds

Bassist Jake Leckie and The Guide Trio Unveil New Album Planter of Seeds,

to be released on June 7, 2024

Planter of Seeds is bassist/composer Jake Leckie’s third release as a bandleader and explores what beauty can come tomorrow from the seeds we plant today.

What are we putting in the ground? What are we building? What is the village we want to bring our children up in? At the core of the ensemble is The Guide Trio, his working band with guitarist Nadav Peled and drummer Beth Goodfellow, who played on Leckie’s second album, The Guide, a rootsy funky acoustic analog folk-jazz recording released on Ropeadope records in 2022. For Planter of Seeds, the ensemble is augmented by Cathlene Pineda (piano), Randal Fisher (tenor saxophone), and Darius Christian (trombone), who infuse freedom and soul into the already tightly established ensemble.

Eight original compositions were pristinely recorded live off the floor of Studio 3 at East West Studios in Hollywood CA, and mastered by A.T. Michael MacDonald. The cover art is by internationally acclaimed visual artist Wayne White. Whereas his previous work has been compared to Charles Mingus, and Keith Jarrett’s American Quartet with Charlie Haden, Leckie’s new collection sits comfortably between the funky odd time signatures of the Dave Holland Quintet and the modern folk-jazz of the Brian Blade Fellowship Band with a respectful nod towards the late 1950s classic recordings of Ahmad Jamal and Miles Davis.

The title track, “Planter of Seeds,” is dedicated to a close family friend, who was originally from Trinidad, and whenever she visited family or friends at their homes, without anyone knowing, she would plant seeds she kept in her pocket in their gardens, so the next season beautiful flowers would pop up. It was a small altruistic anonymous act of kindness that brought just a little more beauty into the world. The rhythm is a tribute to Ahmad Jamal, who we also lost around the same time, and whose theme song Poinciana is about a tree from the Caribbean.

“Big Sur Jade” was written on a trip Leckie took with his wife to Big Sur, CA, and is a celebration of his family and community. This swinging 5/4 blues opens with an unaccompanied bass solo, and gives an opportunity for each of the musicians to share their improvisational voices. “Clear Skies” is a cathartic up-tempo release of collective creative energies in fiery improvisational freedom. “The Aquatic Uncle” features Randal Fisher’s saxophone and is named after an Italo Calvino short story which contemplates if one can embrace the new ways while being in tune with tradition. In ancient times, before a rudder, the Starboard side of the ship was where it was steered from with a steering oar. In this meditative quartet performance, the bass is like the steering oar of the ensemble: it can control the direction of the music, and when things begin to unravel or become unhinged, a simple pedal note keeps everything grounded.

The two trio tunes on the album are proof that the establishment of his consistent working band The Guide Trio has been a fruitful collaboration. “Santa Teresa”, a bouncy samba-blues in ? time, embodies the winding streets and stairways of the bohemian neighborhood in Rio de Janeiro it is named for. The swampy drum feel on “String Song” pays homage to Levon Helm of The Band, a group where you can’t always tell who wrote the song or who the bandleader is, proving that the sum is greater than the individual parts. Early jazz reflected egalitarianism in collective improvisation, and this group dynamic is an expression of that kind of inclusivity and democracy.

“The Daughters of the Moon” rounds out the album, putting book ends on the naturalist themes. This composition is named after magical surrealist Italo Calvino’s short story about consumerism, in which a mythical modern society that values only buying shiny new things throws away the moon like it is a piece of garbage and the daughters of the moon save it and resurrect it. It’s an eco-feminist take on how women are going to save the world. Pineda’s piano outro is a hauntingly beautiful lunar voyage, blinding us with love. Leckie dedicates this song to his daughter: “My hope is that my daughter becomes a daughter of the moon, helping to make the world a more beautiful and verdant place to live.”

Bass CDs

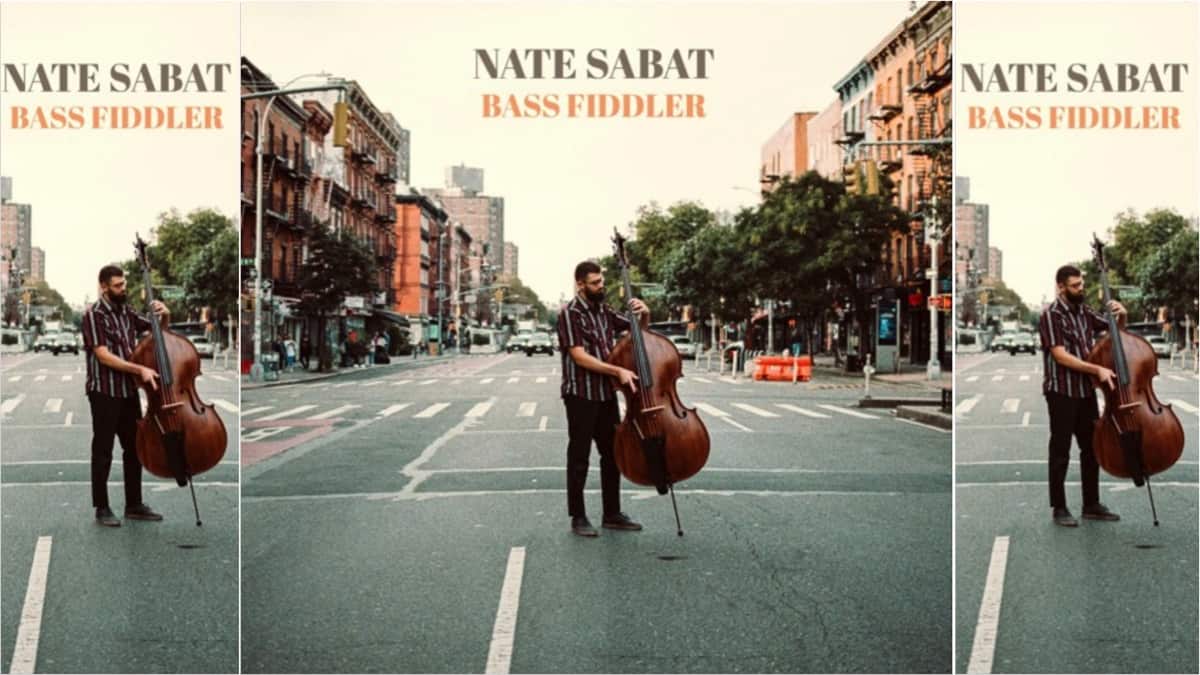

Debut Album: Nate Sabat, Bass Fiddler

In a thrilling solo debut, bassist Nate Sabat combines instrumental virtuosity with a songwriter’s heart on Bass Fiddler…

The upright bass and the human voice. Two essential musical instruments, one with roots in 15th century Europe, the other as old as humanity itself.

On Bass Fiddler (Adhyâropa Records ÂR00057), the debut album from Brooklyn-based singer-songwriter and bass virtuoso Nate Sabat, the scope is narrowed down a bit. Drawing from the rich and thriving tradition of American folk music, Sabat delivers expertly crafted original songs and choice covers with the upright bass as his lone tool for accompaniment.

The concept was born a decade ago when Sabat began studying with the legendary old-time fiddler Bruce Molsky at Berklee College of Music. “One of Bruce’s specialties is singing and playing fiddle at the same time. The second I heard it I was hooked,” recalls Sabat. “I thought, how can I do this on the bass?” From there, he was off to the races, arranging original and traditional material with Molsky as his guide. “Fast forward to 2020, and I — like so many other musicians — was thinking of how to best spend my time. I sat down with the goal of writing some new songs and arranging some new covers, and an entire record came out.” When the time came to make the album, it was evident that Molsky would be the ideal producer. Sabat asked him if he’d be interested, and luckily he was. “What an inspiration to work with an artist like Nate,” says Molsky. “Right at the beginning, he came to this project with a strong, personal and unique vision. Plus he had the guts to try for a complete and compelling cycle of music with nothing but a bass and a voice. You’ll hear right away that it’s engaging, sometimes serious, sometimes fun, and beautifully thought out from top to bottom.”

While this record is, at its core, a folk music album, Sabat uses the term broadly. Some tracks lean more rock (‘In the Shade’), some more pop (‘White Marble’, ‘Rabid Thoughts’), some more jazz (‘Fade Away’), but the setting ties them all together. “There’s something inherently folksy about a musician singing songs with their instrument, no matter the influences behind the compositions themselves,” Sabat notes. To be sure, there are plenty of folk songs (‘Louise’ ‘Sometimes’, ‘Eli’) and fiddling (‘Year of the Ox’) to be had here — the folk music fan won’t go hungry. There’s a healthy dose of bluegrass too (‘Orphan Annie’, ‘Lonesome Night’), clean and simple, the way Mr. Bill Monroe intended.

All in all, this album shines a light on an instrument that often goes overlooked in the folk music world, enveloping the listener in its myriad sounds, textures, and colors. “There’s nothing I love more than playing the upright bass,” exclaims Sabat. “My hope is that listeners take the time to sit with this album front to back — I want them to take in the full scope of the work. I have a feeling they’ll hear something they haven’t heard before.”

Available online at natesabat.bandcamp.com/album/walking-away