Features

From Amateur to Pro: A Discussion with George Farmer by John Kuhlman

George Farmer is a successful working bassist living in New York City with several Broadway shows and recordings to his credit.

A Discussion with George Farmer…

George Farmer (Facebook / website) is an electric and double bassist in New York City. Raised in Vienna, Austria, his earliest musical education came from his father, trumpeter Art Farmer, and later, at the Academy of Music and Performing Arts, Classical Upright Bass performance, and at the Conservatory of Vienna, Jazz Bass performance.

He moved to New York City in 1997 and paid his dues working in a wide variety of musical situations before the higher profile calls started coming in.

George Farmer has played and/or recorded with Art Farmer, Benny Golson, Curtis Fuller, Amel Larrieux, Duncan Sheik, Suzanne Vega, Alexis Hightower, Randy Newman, Eric Roberson, and Omar and Alice Smith. He is endorsed by Rotosound Strings and Aguilar Amplification.

He has worked on Broadway as the bassist for Spring Awakening, which won eight Tony awards, including Best Musical, Best Original Score, and Best Orchestration. The show also captured the Grammy Award in the Cast Album category in 2007.

Farmer was also the bassist for Memphis The Musical on Broadway, which won four Tony awards, including Best Musical, Best Original Score and Best Orchestration.

Most recently, he has had great success as the bassist for six-time Tony Award winner Audra McDonald’s show “Lady Day At Emerson’s Bar And Grill”, which won McDonald’s unprecedented sixth Tony and won the Tony for Best Sound design of a play. The Lady Day cast album topped four Billboard charts in its first week of release: #1 in Cast Albums, #1 in Jazz, #1 in Traditional Jazz, and #1 in Heatseekers.

Bass Musician Magazine: Based on your experience as a working musician, what are the one or two musical skills you see that are consistently lacking in bassists who trying to make the transition from playing at home to gigging for pay?

George Farmer: For the New York scene, I haven’t seen any skills lacking. I think people who come here know what they’re getting into. There are great bass players coming into this city every day. The experience varies, but the musical foundations are there. They know their instruments. They know their amplification. They have their act together.

Now, having said that, there is one issue younger musicians will run into: lack of experience. For example, they haven’t played eight or nine hours every day in a gig setting with their fingers falling off and still have people want to dance. A lot of players coming here straight from college don’t have that experience. It’s not something that can be taught and it only comes from playing. But it’s something that every player has to go through in his or her professional development.

Perhaps my experiences will help put some of this in perspective. I was fortunate to come from a musical family. My father was a musician and there were a lot of musical influences from my mother’s side of the family as well. I started playing piano when I was six and did that for a number of years. I moved to the guitar during my teenage years, and to be honest, gravitated toward the electric bass because four strings are easier than six!

Like many people, after high school, I had to make a decision on what I wanted to do with my life. I wanted to be a musician. However, growing up in Vienna with my family, playing the electric bass was frowned upon. I had to make a deal with my parents to learn to play the upright bass just to appease them.

Farmer is a proficient on both the electric and upright bass. He can frequently be seen with his upright when working with New York artist Alexis Hightower.

I started the upright when I was 18. In order to move forward, I had to pass the college auditions. I went to one of the local college’s clinics and was told to come back after a year’s worth of practice. The man who told me that was Professor Johannes Auersperg from the Academy of Music and Performing Arts. He would later become my teacher and musical guru.

I spent the next 12 months locked in a room learning the upright.

I share that because there is no shortcut to learning your instrument. You do have to spend time working on your craft. The trick is not staying in your practice space. You have to get out and get that experience. And, inevitably, that means you are going to mess up. And probably badly where someone is going to shout at you on the bandstand. It’s going to happen. You just have to get up again and keep going. You can’t let that fear of failure keep you in your bedroom.

Look at it this way. What does our practice space, the bedroom, represent? It’s comfortable. It protects us. Nothing bad can happen to you there. It also means nothing can happen there. It’s a double-edged sword. The bedroom represents your comfort zone and no progress is ever made within the safety net of your comfort zone.

After I completed my studies at the conservatory in Vienna and before that the Academy of Music and Performing Arts, I left my comfort zone and made the move to New York City in 1996. I was fortunate that some of my bandstand failures, my rookie mistakes, were made in Vienna. That allowed me to come into the New York scene without a negative reputation. It also meant I had no reputation.

I freelanced from 1996 to 2006. I played on subway platforms, night clubs, weddings, bar mitzvahs and nursing homes. I sat in on a lot of open mics and went to clinics and took lessons. I had a day gig as a construction worker for almost three years. I worked eight hours a day and played gigs that night. I got out of my comfort zone and had to work hard to increase my experience and build my reputation. And I should add, that I’m still doing that. Getting out of your comfort zone and gaining experience is a life long pursuit.

If you want to make it as a professional bassist, you need to get experience.

BMM: Along a similar line, what about personal or business skills that bassists should have but many don’t bother developing?

Farmer: It doesn’t hurt to save money. I think life business skills are more important than music business skills. Those are the skills that let you save money and make good decisions to invest in yourself instead of wasting money.

As an example, when my day gig was in construction, I had to have good tools. I simply couldn’t work if I had a dull saw or cheap hammer. The same goes for being a working bassist. You have to have reliable equipment that sounds good. Look at your equipment and musicianship as an investment. Not as the latest gadget to acquire or something cheap that will fail when you need it most.

Farmer performing with Suzanne Vega.

This a subject where I’ve noticed an interesting disconnect between the worker and artist mentality. You have cats who don’t believe they have to follow the rules the working man does because they’re creative people.

I believe an artist has the same rules as the working person does. We have the same social phenomena, the same policies, and the same rules. Whatever you can apply to working a regular job should be applied to working as a musician. Yes, musicians have different hours and a different lifestyle. But, to a certain extent, we’re dealing with the same creativity.

Creativity does not live exclusively in the arts. Find someone who’s really good at what they do. It doesn’t matter if they’re a cab driver, surgeon, or construction worker. If they’re good at their job, I bet they love what they do. They also find creative ways to work in their field every day they’re doing their job.

In older cultures, you’ll find that the artist is recognized in everyone. I had the good fortune of playing with many great Gypsy musicians when I lived in Vienna. With them, everyone is an artist. I played with a guy who laid tiles during the day and was a fantastic bassist at night. He was an artist in both roles.

Let’s also not forget that being a musician is a business. We have to be profitable. How much does it take to live the life you’re living? How much is your rent? Transportation? Food? What is the cost to keep your tools in working condition?

Once you figure those numbers out, you have a very objective measurement tool to see where you are. Your perception of a situation can be contaminated by your emotional make-up. The numbers at the end of the day, however, don’t lie. If a gig pays $200 and it cost you $250 to get there, you’re losing money. Even if it’s a rewarding gig on another level, it’s a gigging model that you can’t sustain.

BMM: Speaking of gigs, there seem to be two schools of thought: Take every gig you can to build your experience and network; or be very selective and cultivate your music credentials and reputation. What are your thoughts on building a successful gigging resume?

Farmer: It really comes back to what you like to do. Once you figure that out and figure out the genre, it can go two ways: You can only play that genre and your gigging opportunities will be limited. You will probably have to take a day job or live with the financial help of your spouse, partner, or parents in order to support only playing one style of music. On the other hand, you can be a generalist and play every genre and gig you can in order to make a living. But, you have to remember to also play the music you love when you’re a generalist.

There’s nothing wrong with taking a day gig and paying the bills if your heart is in one genre of music. As a generalist though, you will have more options. You can make gigging your day gig. You can play weddings, socials, night clubs, etc. and still have your style of music that you’re really into and not only pursue that style, but also excel at it.

Now, you have to ask yourself what does it mean to be a specialist? You need to have your own sound and your own unique approach to music. Are you going to get that approach by only playing one style of music? Or is that going to be a culmination of your experience from other types of music? I don’t think that being a specialist or a generalist is necessarily exclusive to each other.

Farmer performing on the upright bass with Benny Golson in Athens, Greece.

You are in charge of your career. These choices are not being made for you. As the player, you are ultimately responsible for the outcome.

To be more specific about taking or not taking gigs…I’m not a big fan of being selective about your gigs. It’s not to your advantage to be that picky. You have to get out there and get beat up a couple of times. It’s a good thing. You build a reputation by delivering a solid product. Your reputation is solidly linked to intent. Your intent should be to play the hell out of any and every gig. And even if you fail, your intent is still there and will be recognized.

BMM: If you had five minutes to sit down with a young musician who wanted to make a go of it as a professional bassist, what would you tell him or her?

Farmer: Get out of your comfort zone. Go out and play as much as you can. Go out and listen as much as you can. There’s no way around that.

If the scene in your town is such that you can just walk down the block to a gig, then do it. If there is no scene in your town, find one in another town. Take a close look at your personal and financial situation and decide if you need to move.

A player plays. Period. He or she will do everything in their power to continue to play. If that means taking a day gig in order to be a musician on the weekends, then that’s what you do. If that means taking every gig that’s offered to you, then that’s what you’re going to have to do. I’m not much for easily saying “no” to something. I’m too curious and you will never believe how interwoven situations are. Someone who heard you five years ago may hire you tomorrow. The more you can open yourself up, the better it is for you.

I have a personal philosophy that whatever is out there, in terms of music, I can do it. I may not be the best at it. If I can’t do it well, then what do I need to learn or practice, to do it well? It’s part of the experience and personal growth as a musician. You have to overcome your fear of failure.

I have to add one very important point. You need to ask yourself what music speaks to you the most. What do you love to play?

If you’re not playing that music or living that lifestyle, then you need to analyze your situation. Are you taking the necessary steps to achieve your objectives?

The players that we look up to ask those questions of themselves and have found, or are in the process of finding, those answers.

Bass Videos

Tour Touch Base (Bass) with Ian Allison

Ian Allison Bassist extreme…

Most recently Ian has spent the last seven years touring nationally as part of Eric Hutchinson and The Believers, sharing stages with acts like Kelly Clarkson, Pentatonix, Rachel Platten, Matt Nathanson, Phillip Phillips, and Cory Wong playing venues such as Radio City Music Hall, The Staples Center and The Xcel Center in St. Paul, MN.

I had a chance to meet up with him at the Sellersville Theater in Eastern Pennsylvania to catch up on everything bass. Visit online at ianmartinallison.com/

Features

Interview With Audic Empire Bassist James Tobias

Checking in with Bergantino Artist James Tobias

James Tobias, Bassist for psychedelic, Reggae-Rock titans Audic Empire shares his history as a musician and how he came to find Bergantino…

Interview by Holly Bergantino

James Tobias, a multi-talented musician and jack-of-all-trades shares his story of coming up as a musician in Texas, his journey with his band Audic Empire, and his approach to life and music. With a busy tour schedule each year, we were fortunate to catch up with him while he was out and about touring the US.

Where were you born and raised?

I was born in Dallas, Texas and lived in the Dallas area most of my life with the exception of 1 year in Colorado. I moved to the Austin area at age 18.

What makes the bass so special to you particularly, and how did you gravitate to it?

I honestly started playing bass because we needed a bass player and I was the one with access to a bass amp and bass. I played rhythm guitar and sang up until I met Ronnie, who I would later start “Audic Empire” with. He also played rhythm guitar and sang and we didn’t know any bass players, so we had to figure something out. I still write most of my songs on guitar, but I’ve grown to love playing the bass.

How did you learn to play, James?

I took guitar lessons growing up and spent a lot of time just learning tabs or playing by ear and kicked around as a frontman in a handful of bands playing at the local coffee shops or rec centers. Once I transitioned to bass, I really just tried to apply what I knew about guitar and stumbled through it till it sounded right. I’m still learning every time I pick it up, honestly.

You are also a songwriter, recording engineer, and a fantastic singer, did you get formal training for this?

Thank you, that means a lot! I had a couple of voice lessons when I was in my early teens, but didn’t really like the instructor. I did however take a few lessons recently through ACC that I enjoyed and think really helped my technique (Shout out to Adam Roberts!) I was not a naturally gifted singer, which is a nice way of saying I was pretty awful, but I just kept at it.

As far as recording and producing, I just watched a lot of YouTube videos and asked people who know more than me when I had a question. Whenever I feel like I’m not progressing, I just pull up tracks from a couple of years ago, cringe, and feel better about where I’m at but I’ve got a long way to go. Fortunately, we’ve got some amazing producers I can pass everything over to once I get the songs as close to finalized as I can.

Describe your playing style(s), tone, strengths and/or areas that can be improved on the bass.

I honestly don’t know what my style would be considered. We’ve got so many styles that we play and fuse together that I just try to do what works song by song. I don’t have too many tricks in the bag and just keep it simple and focus on what’s going to sound good in the overall mix. I think my strength lies in thinking about the song as a whole and what each instrument is doing, so I can compliment everything else that’s going on. What could be improved is absolutely everything, but that’s the great thing about music (and kind of anything really).

Who were your influencers in terms of other musicians earlier on or now that have made a difference and inspired you?

My dad exposed me to a lot of music early. I was playing a toy guitar while watching a VHS of Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble live at SXSW on repeat at 4 years old saying I wanted to “do that” when I grew up. I was the only kid in daycare that had his own CDs that weren’t kid’s songs. I was listening to Led Zeppelin, Hendrix, and The Doors when I could barely talk. I would make up songs and sing them into my Panasonic slimline tape recorder and take it to my preschool to show my friends. As I got older went through a bunch of music phases. Metal, grunge, rock, punk, hip hop, reggae, ska, etc. Whatever I heard that I connected to I’d dive in and learn as much as I could about it. I was always in bands and I think I kept picking up different styles along the way and kept combining my different elements and I think that’s evident in Audic’s diverse sound.

Tell me about Audic Empire and your new release Take Over! Can you share some of the highlights you and the band are most proud of?

Takeover was an interesting one. I basically built that song on keyboard and drum loops and wrote and tracked all my vocals in one long session in my bedroom studio kind of in a stream-of-consciousness type of approach. I kind of thought nothing would come of it and I’d toss it out, but we slowly went back and tracked over everything with instruments and made it our own sound. I got it as far as I could with production and handed it off to Chad Wrong to work his magic and really bring it to life. Once I got Snow Owl Media involved and we started brainstorming about a music video, it quickly turned into a considerably larger production than anything we’ve done before and it was such a cool experience. I’m really excited about the final product, especially considering I initially thought it was a throwaway track.

Describe the music style of Audic Empire for us.

It’s all over the place… we advertise it as “blues, rock, reggae.” Blues because of our lead guitarist, Travis Brown’s playing style, rock because I think at the heart we’re a rock band, and reggae because we flavor everything with a little (or a lot) of reggae or ska.

How did you find Bergantino Audio Systems?

Well, my Ampeg SVT7 caught fire at a show… We were playing Stubbs in Austin and everyone kept saying they smelled something burning, and I looked back in time to see my head, perched on top of its 8×10 cab, begin billowing smoke. We had a tour coming up, so I started researching and pricing everything to try and find a new amp. I was also fronting a metal band at the time, and my bass player’s dad was a big-time country bass player and said he had this really high-end bass amp just sitting in a closet he’d sell me. I was apprehensive since I really didn’t know much about it and “just a little 4×10” probably wasn’t going to cut it compared to my previous setup. He said I could come over and give it a test drive, but he said he knew I was going to buy it. He was right. I immediately fell in love. I couldn’t believe the power it put out compared to this heavy head and cumbersome cab I had been breaking my back hauling all over the country and up countless staircases.

Tell us about your experience with the forte D amp and the AE 410 Speaker cabinet.

It’s been a game-changer in every sense. It’s lightweight and compact. Amazing tone. And LOUD. It’s just a fantastic amp. Not to mention the customer service being top-notch! You’ll be hard-pressed to find another product that, if you have an issue, you can get in touch with the owner, himself. How cool is that?

Tell us about some of your favorite basses.

I was always broke and usually working part-time delivering pizzas, so I just played what I could get my hands on. I went through a few pawn shop basses, swapped in new pickups, and fought with the action on them constantly. I played them through an Ampeg be115 combo amp. All the electronics in it had fried at some point, so I gutted it out and turned it into a cab that I powered with a rusted-up little head I bought off someone for a hundred bucks. My gear was often DIY’d and held together by electrical tape and usually had a few coats of spray paint to attempt to hide the wear and tear. I never really fell in love with any piece of gear I had till I had a supporter of our band give me an Ibanez Premium Series SDGR. I absolutely love that bass and still travel with it. I’ve since gotten another Ibanez Premium Series, but went with the 5-string BTB. It’s a fantastic-sounding bass, my only complaint is it’s pretty heavy.

Love your new video Take Over! Let us know what you’re currently working on (studio, tour, side projects, etc.)

Thank you!! We’ve got a LOT of stuff we’re working on right now actually. Having 2 writers in the band means we never have a shortage of material. It’s more about getting everything tracked and ready for release and all that goes into that. We just got through filming videos for 2 new unreleased tracks with Snow Owl Media, who did the videos for both Love Hate and Pain and Takeover. Both of these songs have surprise features which I’m really excited about since these will be the first singles since our last album we have other artists on. We’ve also got a lot of shows coming up and I’ve also just launched my solo project as well. The debut single, “Raisin’ Hell” is available now everywhere. You can go here to find all the links distrokid.com/hyperfollow/jamestobias/raisin-hell

What else do you do besides music?

For work, I own a handyman service here in Austin doing a lot of drywall, painting, etc. I have a lot of hobbies and side hustles as well. I make custom guitar straps and other leather work. I do a lot of artwork and have done most of our merch designs and a lot of our cover art. I’m really into (and borderline obsessed) with health, fitness, and sober living. I have a hard time sitting still, but fortunately, there’s always a lot to do when you’re self-employed and running a band!

Follow James Tobias:

jamestobiasmusic.com

Facebook.com/james.tobias1

Instagram.com/ru4badfish2

TikTok.com/@jamestobiasmusic

audicempire.com

Bass Videos

Interview With Bassist Edmond Gilmore

Interview With Bassist Edmond Gilmore…

I am always impressed by the few members of our bass family who are equally proficient on upright as well as electric bass… Edmond Gilmore is one of those special individuals.

While he compartmentalizes his upright playing for mostly classical music and his electric for all the rest, Edmond has a diverse musical background and life experiences that have given him a unique perspective.

Join me as we hear about Edmond’s musical journey, how he gets his sound and his plans for the future.

Photo, Sandrice Lee

Featured Videos

Follow Online

facebook.com/EdmondGilmoreBass

instagram.com/edmond_gilmore/

youtube.com/channel/UCCYoVZBLXL5nnaKS7XXivCQ

Features

Billy The Kid: Tapping Into Sheehan’s Eternal Youth!

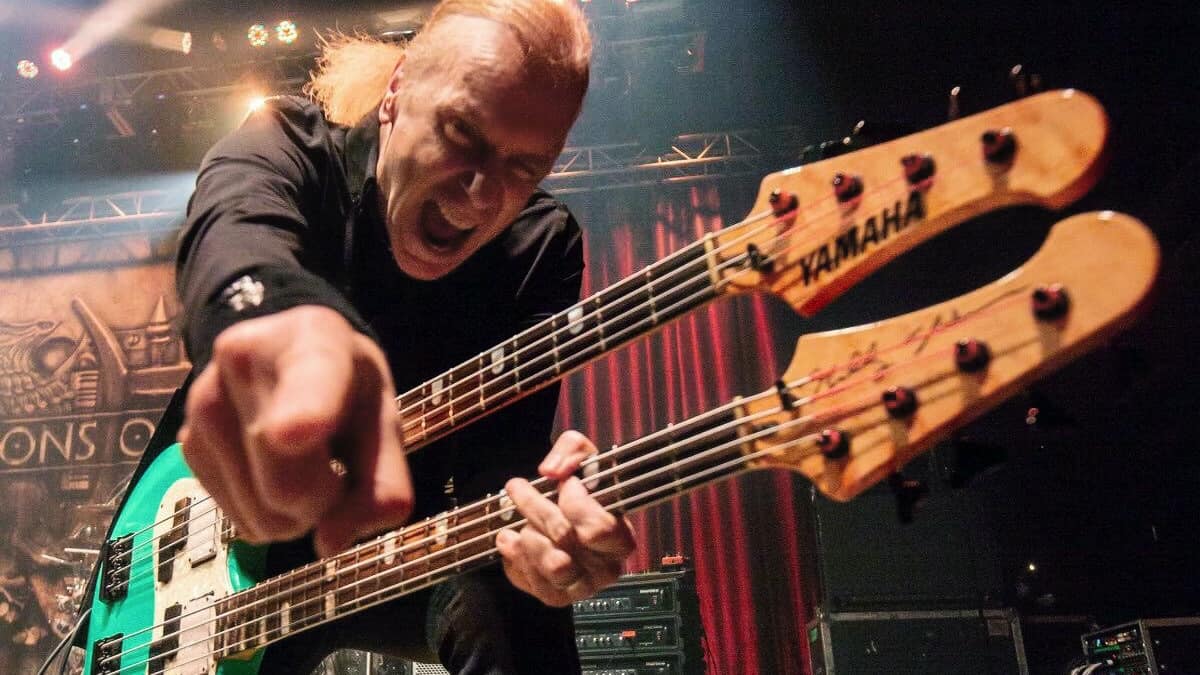

By David C. Gross & Tom Semioli

BS: Billy Sheehan

DCG: David C. Gross

TS: Tom Semioli

“When you find one door, open it up! It leads to another world…”

William Roland Sheehan needs no introduction to bassists, nor hard rock aficionados – however such perfunctory salutations are required for the uninitiated.

A virtuoso (tap, shred, effects maestro – you name it) who plies his craft in genres loosely termed as metal, prog-rock, and heavy-prog, Sheehan is actually a musical polymath. Though he’s most commonly associated with the numerous high-profile voltage enhanced ensembles he’s been an integral part of – namely Sons of Apollo, Talas, Winery Dogs, David Lee Roth, Mr. Big, Greg Howe, Niacin, and Tony MacAlpine to cite a very few – Billy digs everything from classical to jazz to synth-pop to electronic to flamenco to Tuvan throat singing – and then some. All of which is reflected in his work on stage and in the studio – which incidentally, has been going strong for six decades and counting.

With age comes wisdom. We caught Billy in the midst of Mr. Big’s farewell sojourn with his signature Yamaha Attitude bass in his lap. Note that while we were setting up the Zoom connection – Billy was working scales and warming up despite the reality that there was no show scheduled that evening! Sheehan explains why said collective is taking its final bow. Not to worry, the Buffalo-born bassist has much more work to do. In fact, you could say that Billy’s just getting started.

TS: Someone once sang “I hope I die before I get old…” Yet when we take a look around us at a few of your peers and heroes such as Tony Levin and Ron Carter just to name two– they’re going stronger than ever. Reflect on the young Billy Sheehan and the 21st Century Billy Sheehan. What’s changed? What is the same?

BS: As you grow you become more focused. I don’t want to say that I’m more mature, because that has other implications!

As a musician – and I think this is true with all artists – we maintain our 16-year-old sensibilities for life! It’s healthy to maintain a youthful exuberance. I’m thankful that I still have it. Somehow that was built into me.

I’m still excited about getting up in the morning and working on my bass playing every day. I’ll be driving in my car and a musical idea will suddenly hit me and I have to get home to pick up my instrument.

Perhaps it’s because we can devote more time to things at this point in our lives. Hopefully, we’re not running around trying to get our lives together and we have more stability. That can lead to a new personal Renaissance for the over 50s players. It’s a great time to be alive at my age.

DCG: Do you think the snow in Buffalo helped you develop into a virtuoso player?

BS: Absolutely! (laughter) I remember the Blizzard of ’77! I couldn’t leave my house. The snow was up to my chest. I think we went something like 60 to 90 days with the temperature not getting above freezing. I had my little apartment, my little bass, my little heater – so what else could I do?

I learned the Brandenburg Concertos on bass…well, not all of it, just chunks here and there. However, the adversity you get from your environment can be an advantage, like it was for me – I was isolated. I was on my own with no interruptions. Back then I was free – no kids, no girlfriend. I froze but I think it paid off!

DCG: There is one bass tip you gave me – not personally, it was in an interview – regarding strap length. The advice was to simply grab a piece of leather, sit down the way you practice, put the leather on you, stand up, and that is the optimum position for your bass!

BS: Of all the fancy stuff I’ve tried to show people I’ve received more response from the strap length than anything else.

But it’s really important. I’m sitting here with my bass practicing. When I stand up to play live, I need it to be in the same place. You need to maintain the angles of your hands, fingers, and arms. If you get up to play and the bass is lower nothing seems to work.

DCG: That’s because you’re not using the muscles you’ve developed during practice. However you do want to look cool on stage, and the low-slung bass is the ultimate rock star aesthetic.

BS: Right, which is why we should invent a strap with a button on it to instantly lower and raise the bass! (laughter)

Note: Billy proceeds to model different bass lengths – chest level for progressive rock, and under his chin for what Sheehan terms as ‘the jazz bowtie.”

TS: You came to prominence in a decade known as the 1980s which to my ears was a golden era for bassists. Our instrument was able to adapt to the new technologies. The improvements in recording and pro audio allowed bass notes to be heard rather than a low rumble lost somewhere in the mix.

BS: It was a great decade. There is a constant evolution going on. It goes from artist to artist. One artist hears somebody – let’s say Oscar Peterson hears Art Tatum – and suddenly we have this amazing confluence of both styles together. I learned from many of the players that came before me – it’s a long list – everybody imaginable – and some not. Consequently, I stood on their shoulders.

Today there are people who are standing on my shoulders! There is a whole generation of players who are doing what we thought was impossible – or couldn’t even imagine. And that’s a great thing. We see that happen in all the arts.

In music, more than anything, we notice a significant ascension in skills. Some other art forms go off into abstractions whereas in music, there is a real technical, definable and quantifiable ability to play a string of notes in time, in tune, and righteously. That has gone way, way up to me.

I have a huge collection of music. I often focus on one particular brand of music – for example: garage rock from the 1960s. There is rarely a bass in tune! Not even close – sometimes a half step off! Why nobody noticed it, I’ll never know!

As we progressed, it got much better – more in tune, in time.

My first concert was Jimi Hendrix. I went to see him play and I got up close and took a few photos. That was as close as I ever got to him. Now on YouTube – you can see his fingerprints as he’s playing. You can see the iris in his eyes. You can watch and learn everything. I think that is a great advantage to a new generation of players.

They are fortunate in ways that we never were in that there are amazing documents of the musicians that came before them. So now the shoulders are even wider to stand on! Before that the best we could do, as you guys know, is listen to a record and go ‘I think it’s this (Billy renders imaginary riff)! I’m not sure…’ We find out later that we were either right on the money or somewhere in between.

TS: However, ‘getting it wrong’ sometimes develops your individual style. Even if I couldn’t get John Entwistle’s line perfectly, I came up with something else that is unique to me.

BS: Very true! You had to improvise and try to figure out how they did it. As a result, we have the ability to play stylistically. And the mechanics can be wildly across the spectrum of innovation.

I traveled to Japan years ago to participate in a huge bass clinic. There were 3000 people in the auditorium and about 10 players on stage. One bassist played this complicated piece that I had recorded. And he did it exactly, but his technique was nowhere near the way I played it. It was amazing and it taught me a lot. He took a left turn and still landed in the right place. Awesome!

As you both know, there are a million factors that go into this. There are many paths to express yourself, and to be the way you want to be.

TS: Growing up in the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s – we heard pop music on the radio with such extraordinary players as James Jamerson, Chuck Rainey, Louis Johnson, to name a few. Aside from metal, alternative, country, and funk – there hasn’t been a bass on hit tunes – even with such contemporary R&B artists such as Rhianna, Cardi B, and Beyonce – how do we get our instrument back into the mainstream?

BS: I think it is cyclical. That sub-sonic, sub-harmonic pre-programmed thing – you know where they pump the bass line, or make a midi-file of it – is very popular now. And sonically – it is bassier! It’s more precise, and right on.

That is the style that people’s ears are used to right now. They are also acclimated to auto-tune vocals. When they hear a natural vocal, which 99% of the time is not in perfect pitch, it throws them! Nowadays every note lands perfectly on that ProTools grid. The vocals are tuned to perfection, there is not a slightly flat or slightly sharp note to be found.

I think the pendulum will swing back at some point. People are going to want to hear more humanity. They gravitate to something slightly out of time or out of tune which gives the music authenticity. Like taking a breath – we all do not inhale and exhale at the same rate. Our hearts do not beat at the same rate! I believe that there is an analogy there for music as well.

At present, we are in the perfection stage. There is beauty to that too. I don’t put it down. There’s not much about music that I do not like. Millions of love this type of music, and I acknowledge it. Who am I to say? There are a lot of cool things to think about. Especially in electronic music that was coming out in the 80s and 90s – artists such as Prodigy, Fat Boy Slim.

DCG: Yes, it was very experimental.

BS: I loved that right away. There was a Stacey Q song ‘Love of Hearts’ with the coolest synth bass part. I remember sitting down and my challenge to myself was to work that out on a bass guitar. I tried to play it as rock solid as the programmed track. Sometimes it’s good to go with ‘man vs. machine!’ and try to match up to that studio perfection. And that goes for any musician, not just a bass player. You have to push yourself in different directions. When you find one door, open it up! It leads to another world…

DCG: The older we get the more we appreciate things, and even in new music -which may not speak to us per se – there is something to be learned. For example, Justin Timberlake commented that he commences the songwriting process with beats as opposed to traditional chord changes and melodies – which is how our generation hears music.

BS: This is true. And when I was young, I remember the older generation saying ‘What is this Jimi Hendrix stuff you’re listening to, it’s not music!’

And now I see a lot of young folks at our shows – especially Winery Dogs and Sons of Apollo – so there is somewhat of a generational hand-off going on today.

My mom was big into the standard singers of her era; Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Mel Torme, Ella Fitzgerald, Bobby Darin, and similar artists. I am big into Sinatra!

DCG: What is your favorite Sinatra record?

BS: That would be Live at The Sands! Of course!

DCG: Mine is Frank Sinatra Sings for Only The Lonely.

BS: That’s a good one! Live at The Sands is a compilation of five shows. It is a collection of the best parts of five nights…

DCG: Quincy Jones did the arrangements!

BS: Right! I found recordings of all the other shows! That’s the nature of my collection. I always search out the impossible. I also have the rehearsals for Jimi’s Band of Gypsys before they ever performed. It’s amazing to hear different versions of those songs.

Getting back to your comment on the components of music from this generation to the previous ones– I think it’s harder to go from the standard verse-chorus-bridge to a flat beat and vocalizations without any real pitch. That is a big jump.

Yesterday I was discussing the chord changes in Beatles songs with a colleague of mine. For me, the greatest song ever written is The Beatles ‘If I Fell.’ How elaborate they were. I remember learning Everly Brothers songs on guitar and then the Beatles came out and it changed everything. I recall thinking ‘How does this even work?’ That was a jump back then, now what is happening is an even bigger jump because there were still harmonic relations between new and older music.

But that does not mean that the new way of doing things for some artists cannot be crossed over. Again, I appreciated a lot of new stuff. The computer-generated stuff, I’m not crazy about it because many of my friends are musicians and I like to hear them playing instead of programming. Yet there is a real beauty to electronic music.

I was way into Wendy Carlos (composer/recording artist who was a 1960s electronic music pioneer and worked with Robert Moog, inventor of the Moog Synthesizer) back in the day. There was a great record by Mark Hankinson entitled The Unusual Classical Synthesizer (1972). I love the work of Japanese synthesist (Isao) Tomita – he wasn’t doing rhythmic Bach and Beethoven – he was doing Debussy on synthesizer which was mind-blowing to me. His record of Debussy Snowflakes Are Dancing (1974) – is full of lilting, emotional pads and colors. Just incredible.

I’m also a big fan of world music – though that is a title that is too often misused. Bulgarian choir music intrigues me.

DCG: How about the Tuvan throat singers…

BS: Oh yeah, that is not human! Unbelievable. And they’re all in a room singing… I am also a huge fan of Indian music especially violinist L. Shankar whom Frank Zappa referred to as the best musician he ever knew.

And it’s all available now…

TS: You bring up the topic of streaming music – and a question to all the artists David and I speak with. Given the nature of the platform, which is song-oriented, is the album format still relevant today?

BS: To some of us, the format is still relevant. When I’m on tour we sell lots of vinyl. The 1985 Talas record came out on vinyl and we have a hard time keeping up with it. The pressing plants are backed up from six months to a year in some instances.

I saw one columnist comment that he didn’t know if people were actually playing the records as much as they enjoyed holding them in their hands!

Who knows, there may be a time when the grid goes down and everyone is going to have to get their bicycle out, or their generator and get a turntable going again!

DCG: Tom, how do you make a musician complain?

TS: Give him a gig!

(laughter)

BS: That’s true! The internet has brought on the age of complaining…

TS: Musicians complained that the record labels were unfair gatekeepers. When MTV came along – a platform that gave massive exposure to scores of artists – yourself included; musicians once again complained that it favored only the visuals as opposed to the music. Now with digital technology, musicians can go directly to the consumer.

BS: For lack of a better word, things are more ‘democratic’ now. You can accelerate your promotion. For example, I am on a laptop now and I can record an entire symphony orchestra and do the movie soundtrack along with it. Then I can go online and sell it. That has leveled the playing field quite a bit. Before, you could only do that if you had a big budget – you’d have to hire a studio, engineers – it was cost-prohibitive in many instances. You can even do it on an iPhone!

So, to me, that’s a good thing.

I’ve heard of this parallel with this, perhaps you will concur with me; when desktop publishing first came out the reaction was ‘Oh no, there will be so many amazing books we won’t know what to do anymore!’ However, the same number of books still made it to the top of the list – despite the fact that there are hundreds of thousands of people writing via desktop publishing.

And I think the same situation exists with music. Despite the population of the world making music, there is still going to be stuff that gravitates to the top. So, I don’t think it is so wildly different from when there were gatekeepers as you say.

So that’s a good thing. You can be one click away from a billion listeners. That is amazing. The bad thing is, so are a million other people!

DCG: As I said to Tom yesterday, in 100 years, I don’t think people will be reading.

BS: I agree, and that it sad to see. Because similar to music, you can use your imagination. There is a fantastic book entitled This Is Your Brain on Music (written by neuroscientist Daniel Joseph Levitin, first published in 2006) – and I had a conversation by email with the author.

The creativity that you must have in your mind when you’re reading a book – if a passage reads ‘snow is falling, smoke is coming from the chimneys…’ you can see it and smell it in your mind. You create a cinematic scenario. Whereas in a movie, it’s all spoon-fed to you.

TS: The latest kerfuffle in the music business in 2024 is the use of artificial intelligence. What say you of AI?

BS: I am a purist in a lot of ways. When people ask me for advice about getting into the music business I tell them three things:

1. Get in a band.

2. Get in a band with songs…

3. Get in a band with songs that you sing!

Run the numbers of every bass player, every guitar player and so forth and those three steps are the most successful. AI does not necessarily fit in with that. I have yet to wrap my head around AI to have a solid opinion about it. In general, I am leaning towards humans, humanity, and people thinking up things.

People thought up AI, it didn’t think up itself. And it’s all on a computer which is made by humans! I see the urge to create a robot world where everything is done by robots. But unless somebody programs it…it ain’t gonna happen. So there is that human element that is still essential.

Until we get robots that can program, then they’ll be some self-replicating, and then we’ll wind up with Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Terminator of some sort! That could happen. Science fiction has predicted many things that came to be!

I prefer the Everly Brothers to AI. If and when the whole world goes to hell, we can still sit around a campfire with a guitar and sing songs.

TS: Let’s talk bass for a change. David and I have a credo that states ‘it’s not a real bass until you drill holes in it.’ David now favors custom instruments, though he still loves to tear up a perfectly good bass and rebuild it in his own image every now and then. I prefer to modify my Fender basses. What was your original inspiration to create the legendary ‘wife’ and other basses?

BS: For me, the Fender Precision bass is the bass. Ninety-nine percent of everything has been done on that instrument or some variation thereof.

This (Billy holds aloft his Yamaha Attitude bass) is very P bass-ish. When Yamaha contacted me to make a bass and endorse their instrument – Fender was at a low point. They were changing ownership, there were shifts going on in the company, and their instruments weren’t that great. I’m going to say that was the mid-1980s.

Yamaha came along with quality control second to none in my opinion. I am glad went with them and I will always be with them.

The P bass is undeniable. Before my first P bass came into the store – that was Art Kubera’s Music Store on Fillmore Avenue in Buffalo, New York – they let me take home an Epiphone Rivoli bass – or the Gibson version of that, which had the big, fat chrome pick-up right here beneath the base of the neck. It had a super deep low-end resonance.

I played for a few days, and when my bass came in I played it and it sounded great but it was missing that sound from the Rivoli. It was a super deep low sound like I’d heard on ‘Rain’ by The Beatles – which may have been Paul’s Rickenbacker or Hofner.

Notes From An Artist Notes: Paul’s aforementioned instruments both featured pick-ups beneath the base of the neck and body!

Paul Samwell-Smith of The Yardbirds, who used an Epiphone Rivoli – was a big inspiration to me and he had that deep sound.

I loved the P bass but I wanted those sounds so I figured ‘Hey, I’ve got all this space right here, why don’t I dig a hole and put a pick-up in there!’ I didn’t know how to wire it, so I made two outputs and ran it into two channels of my amplifier. We’re talking 1970…1971. When dinosaurs roamed the earth!

Then I got a second amp – one was for all the harmonics and high-end content and then the super low deep end on the other. That really helped me in a three-piece band. We didn’t have a keyboard or rhythm guitar, so I had something that sounded guitar-ish and keyboard-ish but there was always bass underneath it. I never lost that low end. And that is basically the formula I stuck with.

Then I found out later on – of course, I did not invent it, I came up with it on my own – all the others did too, that all the early Alembic basses had duel outputs for each pickup. Rickenbacker’s Rick-O-Sound had both pickups going to two places.

I’d read that John Paul Jones of Led Zeppelin took his Fender Jazz bass and split the pick-ups into two amps. John Entwistle did stuff like that as well. Chuck Burghofer, who played the iconic bass part to the Barney Miller show theme song had a Gibson EB-0 pick-up on his Precision bass! A lot of players used that for the same solution to the same problem.

If you really want to extend the low end – that neck pick-up is really where it is at. And that’s how I got to where I am on my Attitude bass. The Attitude neck is modeled after a 1968 Fender Telecaster bass – it’s a big fat baseball bat! It’s meaty with a lot of sustain. And that’s my story sad but true! (laughter)

TS: The great Mel Schacher of Grand Funk Railroad modded out his Fender Jazz with an EB-1 pickup at the neck – that’s how he attained his signature tone.

BS: One of my favorite players!

TS: Since our show commenced three years ago as The Bass Guitar Channel David and I have debated the merits of the extended-range bass. You’ve always been a four-string guy. I last saw you with Sons of Apollo with a double neck bass – with both in four-string configurations.

David and I spoke with Jerry Jemmott, the legendary bassist who, as you know, was a great influence on Jaco Pastorius. He maintains that Jaco would have continued with the four-string had he lived to see the advancements in extended-range five and six-string instruments. He also stresses that it was the limitations of the four-string that were a major factor in Jaco’s style – it prompted him to be more creative within those so-called restrictions. Your thoughts?

BS: I’ve already got enough death threats from five and six-string players! (laughter)

I refer to the five-string bass as a ‘flinch.’ You have a guy sitting at home playing a four-string, it’s not really working out for him. He’s not playing in a good band… he’s not happening. So he thinks ‘I’ll go to five-strings!’

DCG: Oh Jesus!!!! C’mon Billy…

BS: Well, that’s really not a true blanket statement… (laughter)

Really, if you want to play five-string, God bless you, go for it! Go for however many strings you want.

When I posted my double-neck on social media, there was a ton of vitriol! Hostility! Attacks! I got feedback such as ‘You should play a five-string, that’s just wasteful!’

Hold on, I played a double-neck for a lot of different reasons. First of all, they are tuned differently. On the Mr. Big tour, we had to lower the keys on many songs. We’re not like we used to be vocally. Some of our songs are a whole step lower – so I’d have to switch basses, which would interrupt the flow of the performance. With the double-neck, I have every tuning I need right here.

It seems like nobody could figure that out, especially the five-string. The double-neck is a fantastic instrument, it feels good, and it’s perfectly balanced for me. Standard tuning on the top neck, BEAD on the bottom. All my notes are where I want them to be.

I agree with Jerry, I think Jaco would have stuck with the four-string. Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen played four strings. Monk Montgomery… There really is no limitation on a four-string.

I can bend my Attitude on the G string to a high G. I can go really low with my de-tuner. I can bend the low D to a low B! So I have almost the same range as a lot of extended ranges basses right here.

I remember being in a band with Steve Vai and I had one low B note in one song, so I simply hit the de-tuner! Where there is a will there is a way!

If you want to play a 90-string bass, I’m with you! The insistence that we all have to play the same bass with the same tone with the same everything – and if you don’t – you’re out of the club! I can’t hang with that.

TS: You’ve collaborated with so many virtuoso guitarists – Steve Vai, Tony MacAlpine, Ritchie Kotzen, Paul Gilbert, and Michael Schenker to select a scant few. Who are the players, past or present, whom you would like to work with the most?

PS: Sadly we lost that guitar player, and I don’t think I am qualified either: Paco de Lucia! He was tops on my list. Also I have to add John McLaughlin to the list. I am a huge Mahavishnu Orchestra fan. I am a big Billy Cobham fan too.

You mention guitar players, but I am more of a ‘drummer’ guy! I got to see Cobham in Dreams before the Mahavishnu Orchestra with the Brecker Brothers on horns for $1.50 at the University of Buffalo. He blew my mind!

I love Dennis Chambers. Playing with him changed my life.

DCG: Tell us how you approach working with guitar heroes.

BS: I like to work ‘with’ guitarists. I do what they need to have done. In the past when I played with Steve Vai, I removed myself from the equation. My approach was ‘What does Steve want? What does he need?’ In some ways, it takes the burden off me to be continuously creative. I strive to play accurately and righteously and make him happy. I don’t want him to even think of the bass while he is doing his thing.

He is free and I am providing that big foundation – think of it as 18 inches of steel-reinforced concrete! With Paul Gilbert in Mr. Big, I always make sure there are big fat notes underneath him while he is soloing and I get the heck out of his way! I want to hear him too!

Bass is primarily a supportive instrument. Most anybody will agree to that I believe. The instrument does its own things too; sometimes its really woven into improvisation, sometimes it’s the foundation.

The problem I have with some guitarists is that if I move harmonically – they get thrown off because they cannot play over changes. Even if I am in the key of E minor, if I do some movement in the key other than the root, they are completely lost. I tell them not to worry, we are still in the same key!

If you listen to Bach, what he does in the left-hand affects the sound of the right hand. The moving notes create intriguing counterpoint which are essential components of music and harmony.

Depending on the guitarist, I’ll move around all over the place. Within reason of course! I give them the option to go where they want to go, and not to work because I’ll follow you! I will instinctively get out of the way when you need me to. Lock in with the drummer and I’ll jump in when it’s time. This way we create an interchange – an improvisation. Again, think Bach with the left hand and the right hand. You hit one note, you hit another, and something changes! That is harmony. It creates a third tone in a way.

When you can do that as a bass player it leads to more harmonic complexity in a good way.

That’s not to say that Cliff Williams in AC/DC isn’t a genius. He’s pounding that beautiful open E string while Angus is doing his thing and it is glorious. Amazing. Same thing with Ian Hill of Judas Priest – he holds the whole band together.

TS: And on the topic of drummers, Michael Portnoy and you have two remarkable bands that are completely different: the prog-rock collective of Sons of Apollo, and the blues-based Winery Dogs.

BS: Winery Dogs is straight-up rock with a lot of improvisational stuff. Sons of Apollo is more of a progressive arranged style – the parts are the same – they are written into the song, much like classical music. As you can hear, there is not as much free form moving in Sons of Apollo.

Sometimes I have this ESP thing going on with drummers. I remember one time I was setting up in a little club to do a jam and drummer Ray Luzier of Korn – we are dear friends and have a production company together – I had my back to him and I was plugging in my little amp. The lights were down and while we were playing Ray just hit his bass drum – boom! at the exact moment when I hit my E string – boom! We spun around and looked at each other and said to each other ‘how did you know!’ (laughter)

When a drummer goes chicka-ta-ba-ba-do-bop, I play chicka-ta-ba-ba-do-bop! You can really incorporate motion in the bass into a useable, uncluttered thing if you are really locked in with the drummer. That’s something I tell young players all the time.

Start on the bass drum – when the drummer hits the kick – the bass player hits a note. Same with the accents. Then later on if you want to do it you can play lower and higher octaves with the bass and snare drum – ala The Knack on their hit ‘My Sharona.’ There are so many hits constructed on that way of doing things: ‘Gimmie Some Lovin’ by Spencer Davis – there are many examples.

If you want to get adventurous you play along with the tom-tom fills! That’s my thing. I build my basslines more on drums than guitars.

TS: Moving from Sons of Apollo to Winery Dogs is just another day at the office for you…

BS: Fortunately, I grew up in a time where my bands’ setlists were wild. Like everyone else, I started off in copy bands. My groups played everything from The Tubes –‘White Punks on Dope,’ to King Crimson’s ‘21st Century Schizoid Man,’ to Three Dog Night’s ‘Joy to the World,’ to Grand Funk Railroad…all this diverse stuff. A broad array of styles.

When you’re playing in a bar band, you never know who is coming through the door. Some audiences like to hear complex music, other audiences want to sing along with ‘Jeremiah was a bullfrog… was a good friend of mine!’

It was good training for me to get in a situation where I could jump from genre to genre – somewhat convincingly I hope – and still manage to stay on my feet.

TS: Playing Top-40 was a boot camp experience for me as well. We had our disco set, slow dance set, dinner standards set… how is Mr. Big doing on your 2024 farewell tour.

BS: We’re doing great, we’re selling out venues, the feedback has been fantastic. We’re having a ball. And it’s a real farewell tour too – not a fake farewell tour! (laughter)

We want to cross over the finish line standing up rather than crawl over it with a walker and an oxygen mask with backup singers and running tracks! We are still actually singing and playing! I’ll be 71 next month (March 2024) – I am the oldest in the band. Not everyone ages the same, it can be difficult to get up there for a two-hour show.

DCG: Doesn’t it strike you as funny when you go from being the youngest member of the band to being the oldest? (laughter)

BS: My timeline has shifted! I feel great. I still feel like I’m 16. I recall that after the pandemic when I first went out with the Winery Dogs, I felt like an MMA fighter! Get me in the octagon, let’s go! I was dying to play, and we hit it hard. Then I went back to Mr. Big, then back to Winery Dogs again… twice to Japan…two or three times to South America… all within the span of a year.

I’m still ready to go, it’s all good!

Note: Our complete conversation with Billy Sheehan will be available in an upcoming book: Good Question! Notes From An Artist Interviews… by David C. Gross & Tom Semioli www.NotesFromAnArtist.com

Bass Videos

Interview With K3 Sisters Band

K3 Sisters Band Interview…

It is very rare when I talk to a band where all the members play bass. The K3 Sisters Band is a perfect example of a group where Kaylen, Kelsey and Kristen Kassab are all multi-instrumentalists and take turns playing bass.

Hailing from Texas, these three sisters have been playing music since they were very young and have amassed an amazing amount of original music, music videos, streaming concerts, podcasts, and content that has taken numerous social media platforms by storm. On TikTok alone, they have over 2.5 million followers and more than a billion views.

Join me as we hear the story of their musical journey, how they get their sound, and the fundamental principles behind these prolific musicians.

Here is the K3 Sisters Band!

Photo, Bruce Ray Productions

Featured Videos:

Follow Online:

k3sistersband.com/

TikTok

YouTube

Instagram

Facebook