Bass Edu

Unlocking Bass Scales and Chords That Will Make You Sound Unique

Bass Scales and Chords…

This lesson is all about unlocking bass scales and chords that will help to make your sound unique.

Yes, you can take as many music lessons as you want, you can enroll in any bass guitar course that you want, but this still doesn’t guarantee that you’ll be a great musician. In fact, no one can ever guarantee that you’ll become one. At the end of the day, it’s all up to you and how you implement the knowledge you get into your own original music. And no one will ever care whether you’re a self-taught musician or whether you went to a prestigious university.

But with this said, there are still some fun and engaging ways for you to figure out how to sound unique. While we mostly base our music theory knowledge around the standard major and minor scales, major and minor chords, and occasional ventures into 7th chords or a few modes, there are some things that bass players, and musicians in general, might overlook. Although “unconventional,” in the sense that they’re not part of the standard Western music styles that we’re used to, there are some great scales and chords out there that can find their use in modern music.

If you agree with this, we’ve come up with a list of what we thought are the best bass scales and chords that will make you sound unique. These aren’t some “controversial” or “forbidden” elements, but rather scales that are regarded as unusual but can find their use in some practical settings in modern music. If you’re looking for the best ways to spice things up, we’ll share these chords and scales and explain how you can implement them in practical settings. We’ll also present each scale using degrees from a modified major scale.

Bass Scales

Dorian-blues hybrid

Aside from the pentatonic scale, the blues scale is one of the most often ones in modern music. Although we usually associate it with blues, hard rock, maybe even metal music, it can find implementation in mainstream pop music and other genres as well. While the scale is based on the standard minor pentatonic, the addition of the augmented fourth interval, or diminished fifth (depending on how you look at it), really changes the whole vibe.

However, what if you fused this scale with the Dorian mode? It sounds weird, but it’s no rocket science. Just take the pentatonic scale, add a diminished fifth, minor second, and a major sixth. You can then use it for any minor chord progression where a major 6th interval would sound good. It’s a good “jazzy” substitute for the Dorian mode. Presented numerically, it goes:

- 1 – 2 – b3 – 4 – b5 (or #4) – 5 – 6 – b7

Dorian #4

While we’re at Dorian mode, there’s one pretty interesting modification to it. It’s pretty mindblowing how just one note can make a world of difference. In this case, we have a standard Dorian scale, only with its augmented 4th degree. The one-and-a-half step gap between the minor 3rd and the augmented 4th makes it sound mystical, especially when you combine it with the minor second interval in there. However, the major 6th interval makes it kind of weird yet special. It goes something like this:

- 1 – 2 – b3 – #4 – 5 – 6 – b7

Dorian-Mixolydian-Blues hybrid

Now, if you’re a fan of blues-rock, but you want to add real jazzy feel in your songs, then there’s one scale that can help you out. We’ve mentioned the Dorian-blues hybrid above. However, you can also expand this scale with an additional major 3rd interval. This way, you also cover more sonic territories, and it fits well with dominant 7th chords as well. Aside from the I-IV-V progressions, you can implement it with many minor progressions, or any song where a Dorian mode works well. It goes like this:

- 1 – 2 – b3 – 3 – 4 – b5 – 5 – 6 – b7

Locrian mode

Look, there’s hardly any part of any piece of any music genre where you can properly implement the Locrian mode. However, this doesn’t mean that you can’t have fun whit it when writing your bass lines or doing some brief improv runs in specific parts of songs. Yes, it’s difficult to implement, but it’s still isn’t impossible. By writing bass lines or melodies in Locrian mode, you’ll create somewhat of an unresolved and kind of “tense” effect. This is due to its minor 2nd and minor 3rd intervals, in combination with the diminished 5th and the minor 6th. You can either implement it if the entire piece or a section is written in the Locrian mode, or you can use its main 7th chord to create an unusual unresolved tension over a minor chord progression.

- 1 – b2 – b3 – 4 – b5 – b6 – b7

Melodic minor

Yes, the melodic minor scale is no secret. If you’re at least somewhat into music theory, there’s a high chance you’re already familiar with it. However, this scale is so often overlooked, yet it can completely change any of your songs. The problem here is that we have a minor scale with major 6th and major 7th intervals. Or, an easier way to look at it would be a natural major scale with a minor 3rd interval. It’s pretty cheerful-sounding for a minor scale, and it can be implemented instead of the natural minor, in case you want to make things jazzier.

- 1 – 2 – b3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Egyptian pentatonic

We’re all familiar with the good old pentatonic scale that’s pretty much a foundation of modern rock (and even pop) music. But we usually tend to look at it in a very limiting way and not think of its modes. Just like with any scale, there’s also a great minor pentatonic mode that’s referred to as the Egyptian pentatonic. What’s really interesting is that this scale can be used instead of any minor scale and instead of any dominant scale. It’s neither minor nor major, but kind of “universal” for many different settings. Here’s how it goes:

- 1 – 2 – 4 – 5 – b7

Hiraj?shi

While we’re at it, the so-called Hiraj?shi is another great example of a “universal” scale. In its essence, it’s also a pentatonic scale, since it has five degrees. However, we have minor 2nd and diminished 5th intervals in there. And it’s neither minor nor major. Just Hiraj?shi. The lack of a 3rd interval makes it kind of “universal” for different settings and contexts. It is a traditional Japanese scale and has some serious Eastern music vibes.

- 1 – b2 – 4 – b5 – b7

Diminished scale(s)

There’s just something sinister about diminished chords and diminished scales. This is due to the fact that they feel really tense and unresolved, way more than even the Locrian mode and its main 7th chord. But the diminished scale has two variants, both of which alternate between the whole and half steps. The one starts with the half step and the other with a whole step. Here’s how they go:

- 1 – b2 – b3 – b4 – b5 – 5 – 6 – b7

- 1 – 2 – b3 – 4 – b5 – #5 – 6 – 7

They’re also referred to as octatonic scales since they have 8 instead of regular 7 intervals. They’re usually not that easy to implement but are useful for any place where you have a diminished chord in the progression, or anywhere where you’d need to add some tension.

Double harmonic minor (or “Hungarian minor”)

Lastly, we’d include the so-called double harmonic minor, which is also referred to as the “Hungarian minor scale.” And this particular one is known as one of the most depressing-sounding scales of all time. There’s an augmented 2nd interval between its 3rd and 4th degrees, as well as between its 6th and 7th degrees. There’s also a three-note chromatic run in there, making it sound super-dark. Here’s how it looks like:

- 1 – 2 – b3 – #4 – 5 – b6 – 7

Bass Chords

Minor 7 b5

Derived from the Locrian mode, the minor 7th chord with a flat 5th interval is a pretty interesting one. As tricky and unusual as the scale in question, it’s not that easy to implement it. However, it can be quite a colorful addition to your bass-playing vocabulary when used properly. For instance, it comes really in handy if you’re playing a standard II-V-I chord progression in a minor key. In this case, you’ll use it as the first chord in the progression.

Another great way is to use it as a substitute for a minor chord. However, you’ll have to play it with the root note one-and-a-half step lower than the original minor chord. So if you need something to spark up that C minor chord, just play an A minor 7th with a flat 5th. This way, it’s kind of like playing a C minor with an added 6th.

5th chord with #11

Chords with a #11 are pretty unusual, and kind of spooky in some way. But they’re still a pretty useful tool if you need some tension in there without playing a diminished chord or a diminished arpeggio. They’re not that common, but can be pretty interesting if you need to add a passing chord and completely change the vibe of your music. They might be tricky on a bass guitar though, but they’re far from an impossible task to figure out.

“The Call of Ktulu” chords

Do you know Metallica’s instrumental “The Call of Ktulu”? Well, two of those intro chords that the guitar is playing are pretty tense. Essentially, they are A minor add9 and an A minor add9/D#. That D# here is an augmented 11th (or an augmented 4th) interval, which adds a pretty scary-sounding vibe to it.

Minor 7th with added 9th

But if you need something more mellow and relaxing, we’d recommend a good old minor 7th chord with an added 9th interval. Sure, it’ll be easier to pull off if you’re playing a 5-string or a 6-string bass, although it’s also possible to play it on a regular 4-string.

Keep practicing (the payoff is worth it)

Since the bass guitar works on the same principles as a regular 6-string guitar, all of these chords and bass scales will work well in those settings as well. In order to implement them properly and use their full potential, you’ll need to be acquainted with some basic of the basic music theory concepts. When you get that covered, these elements will come in as a perfect tool for your musical expression.

Bass Edu

BASS LINES: Triads & Inversions Part III

Hello bass players and bass fans! In this issue, we will study the triads and their inversions.

In the last months, we have been studying triads in their inversions. This time, we are going to study what is known as the second inversion of the triads.

The second inversion consists of the fifth going on the bass in the triad as we will see below:

C Major Triad (2nd inversion)

G – C – E

C Minor Triad (2nd inversion)

G – C – Eb

C Diminished Triad (2nd inversion)

Gb – C – Eb

C Augmented Triad (2nd inversion)

G# – C – E

See you next month for more #fullbassattack… GROOVE ON!

Bass Edu

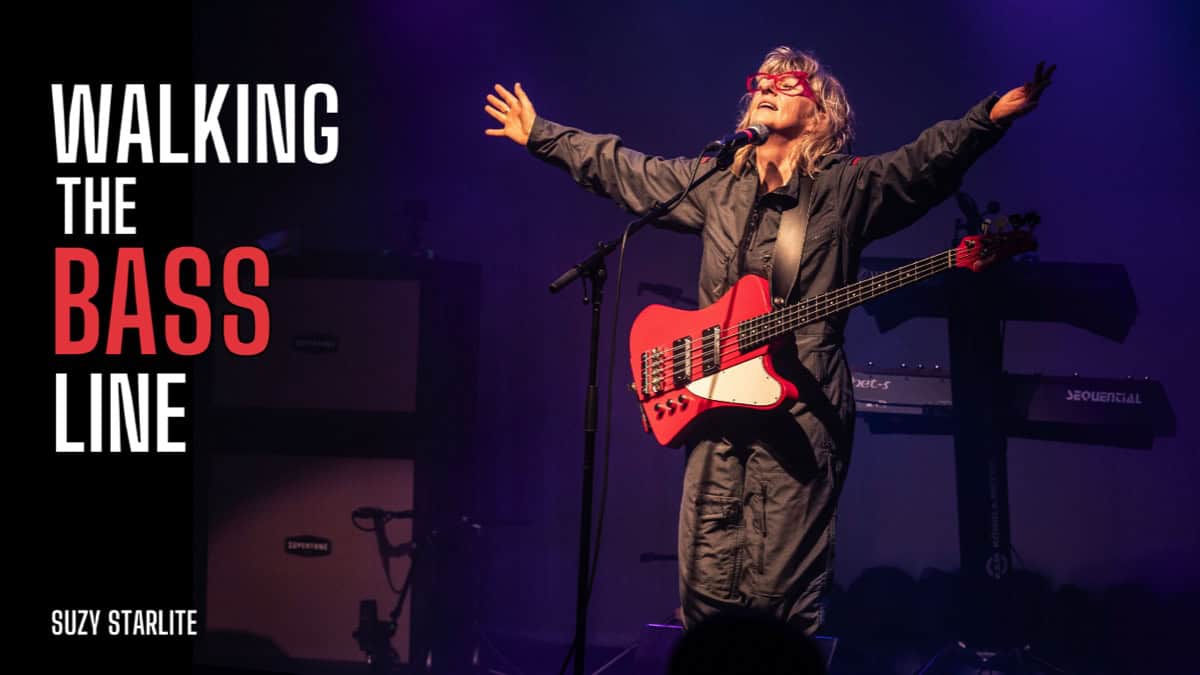

Walking The Bass

I first started playing an acoustic guitar in my band but now find myself working as the custodian of the groove in the bass department, plus keyboards, amplifiers and effects pedals akin to the bridge of the Starship Enterprise. What happened?

When I started off playing musical instruments as a child, life was simple.

There was the harmonica, my favourite sound to inspire random dogs to ‘howl’ along with a simple tune. Then followed descant and treble recorders, my friend Jill’s piano (and anybody else’s come to think of it), the school organ at lunchtimes and a brief awkward dalliance with a cheap violin. Finally, through Hobson’s choice, I settled on the last instrument standing in the school’s musical armoury – an old, unwanted and completely battered French horn. C’est la vie!

I really enjoyed this unusual curly-belled instrument and had lots of fun playing in the school orchestra and brass band, learning a lot about parts and how all the other instruments wove in and out of each other and the incredible melodies and emotions that followed. I was also a member of the school choir in the ‘alto’ department and fell in love with harmonies – it’s just the best!!

Sadly my dalliance with the world of brass had to stop with the installation of fixed ‘cheese-grater’ dental braces. Subsequently, I moved on to the acoustic guitar which allowed me a good deal of independence enabling me to sing and accompany myself with some cool chords. It also ignited my passion for songwriting.

Being heard

In the early 90s I moved to the north of England to study Media & Performance at Salford University and after singing some of my original songs in a lunchtime concert under the moniker of a band called I Never Used To Like Brussel Sprouts I ended up as one of the founding members of a contemporary folk band called Megiddo with some great guys off the degree course in Popular Music and Recording – namely John Smith, Tim Allen and Alan Lowles.

We wrote and performed all our original songs, self-recorded and released an album called On The Outside and toured the UK folk circuit. In those days if you wanted to test out new songs, a good place to go was our local folk club which was based in a pub in a slightly dodgy area in Higher Broughton.

There were no microphones or amplification of any kind – nothing electronic. Everything was acoustic and au natural. You listened to everyone else playing and when it was your turn – you stood up where you were sat – that was your stage.

Of course when we were booked for the bigger gigs we needed amplification for the instruments and vocals to be heard in these vast spaces – but we didn’t use any overt effects or added jiggery pokery with our instruments (two acoustic guitars and a fretless bass – we sounded natural – like us, but louder.

Credit: Steph Magenta ©1995

Megiddo (L-R Suzy Starlite, Tim Allen, John Smith, Alan Lowles)

A few years later, touched by the hand of fate – in a happy, groove-laden serendipitous happening – everything changed and I accidentally got hooked on playing the bass guitar.

I hadn’t been playing that long before my first professional gig, which happened to be with my husband Simon when we toured the UK to promote his second solo album, The Knife.

Credit: Stuart Bebb, Oxford Camera ©2023

Myself and Simon onstage at the Ramsbottom Festival 2015

Simon is a pro and I was in the band because he loved my playing.

As you know I didn’t start out playing bass as my first instrument and the funny thing is, a lot of other bass players didn’t either…

- Lemmy had just joined Hawkwind as a guitar player when he found out he was surplus to requirements due to Dave Brock deciding he was going to play lead guitar instead. But when the band’s bass player didn’t show up for one of their free gigs because he wasn’t getting paid, he had also inadvertently left his bass and amp in their van. So, Lemmy stepped in, and played bass for the first time live on stage at a gig! (That does make me laugh…)

- Flea from the Red Hot Chilli Peppers started out playing the trumpet and was pretty good at it too by all accounts.

- The Who’s thunderous John Entwistle started out on piano, then moved onto trumpet and French horn before he picked up a bass guitar. (Yey I played French Horn at school)

- Jaco Pastorius was first and foremost a drummer and only stopped playing after a wrist injury on the soccer field made it more difficult to play – that, and a better drummer had rocked up on the scene, so he stepped aside for this guy to take his place in the band. It was only because the bass player left at the same time that he picked up the bass!

- Carol Kaye played jazz guitar and by the knock of opportunity, moved onto bass when she filled in for a recording session when another musician didn’t show up!

- Tina Weymouth – who provided the bass-bedrock of Talking Heads signature sound, started out playing handbells – which has slightly freaked me out as I used to play them when I was a teenager too. Apparently, she taught herself guitar before picking up the bass when she formed the band with David Byrne and her now-husband, drummer Chris Frantz.

It’s all about the sound

Moving forward to today – music is not just about being heard anymore. I’m on a new and exciting trajectory, this time experimenting with my bass guitar making different sounds. From pedals to amplifiers to the big cabinets that house the speakers – you could say I’ve become a ‘cosmic explorer of the sonic palette’!

It sounds extra-terrestrial / inter-dimensional – and sometimes feels just like that!

In the beginning

My first bass guitar set up for the tour with Simon back in 2016 was simple: Mike Lull M4V bass guitar – plugged directly into my Sonic Research ST-300 TurboTuner (a guitar tuner) using the Supertone Mincap ‘A’ guitar cable then with a second cable to the back of the stage where it was plugged straight into an amplifier and speaker cabinet provided for me by the gigs/venues.

Since then I have had two different setups and have gradually added a few more bass guitars to my stable… Oh, and some stunning keyboards too.

What’s all the fuss about pedals?

What are guitar pedals and why use them?

This whole saga began in 2018 when we were touring our debut Starlite & Campbell album ‘Blueberry Pie’. Simon and I had formed a new band and had co-written and produced our first album together.

During the recording process, I played two different bass guitars. A Mike Lull M4V and a black Gretsch ThunderJet, both fitted with flat-wound strings.

You may not be familiar with these two beauties (check out the photos below) but as you would expect they have different sounds (aka tonal characteristics) and volumes (output levels), one being lower (quieter) than the other.

In the studio, you have time to set up each sound and when recording our first album together, Blueberry Pie, I needed a gritty, dirty, fuzzy sound for the solo section of You’re So Good For Me.

For this purpose, I employed the kickass assistance of the Supertone Custom Bass FUZZ by DWJ pedal – which I’ll explain more later – just know that I love it!!

FUZZ!!!!!!!

DWJ Supertone Bass FUZZ pedal

Photo credit: Simon Campbell

On tour, however, I needed to use this fuzz and swap between two different bass guitars for certain songs. This is where the wonders of technology, pedals and effects start to help you out.

Watch this video of our Starlite Campbell Band concert at The Met in Bury, Manchester to hear the ThunderJet in action. Geek alert: bass solo at 01:56 minutes.

Bass guitars

It’s probably a good place to give you some information on the two basses in question.

Gretsch ThunderJet

This was my first ever bass, chosen because I’ve got really small hands and it has a shorter neck – hence the term short-scale (shorter scale = smaller distance between the frets). I also wanted to have that short thumpy 60s sound, similar to Jack Bruce (Cream), Andy Fraser (Free) and Paul McCartney – (I think you may know which band).

The ThunderJet has a semi-hollow body so it’s not too heavy and has a big fat distinctive and punchy sound.

It’s also one of the best-looking sexy basses Gretsch has ever produced with a throwback to their vintage models and often people will ask me about it after gigs… upstaged or what?

Technical stuff

- Mahogany body with arched maple top

- Ebony fingerboard

- Semi-hollow body

- Dual TV Jones® Thunder’Tron™ pickups

- Space Control™ bass bridge

- 30.3-inch scale

- Thomastik-Infeld Jazz Bass – JF324 – flat wound strings

Gretch ThunderJet bass guitar

Photo credit: Simon Campbell

Mike Lull M4V

This guitar is ultra-special to me. Not only was it my wedding present from Simon but it was also made by the late great Mike Lull himself.

This is my old friend, the guitar I had imagined, which has been with me from almost the beginning, through endless hours of learning, making mistakes, jumping around with me when the music takes you high. We recorded most of the songs on Blueberry Pie with this bass and have played many a festival stage together, flown on planes and travelled around the world and back again.

The low end has a big attitude for rock and an elegant versatility that lets you slide up the neck as if you were on your knees sliding across a well-oiled floor! Sometimes I close my eyes and imagine it’s an upright double bass too, the sound and thud of the strings taking me to that smoky downtown bar.

The M4V evokes a fantastic classic vintage vibe with all the wonderful attributes of a 60/70s Jazz bass combined with passive electronics, all in a slightly downsized body shape.

Technical stuff

- Fitted with Hipshot Ultralite tuners with drop D

- Custom Wound Lindy Fralin Single Coil Pickups

- Hipshot Aluminium Bridge

- Mahogany Body

- Graphite Reinforced Maple Neck

- Rosewood fingerboard

- Thomastik-Infeld Jazz Bass – JF344 – flat wound strings

Mike Lull M4V bass guitar

Photo credit: Simon Campbell

Technical terminology/gear

At this juncture, I also needed to get my head around a few basic technical terms and learn about how things work.

What is that saying: It’s not easy because I haven’t learned it yet.

The guitar pick-up

Have you ever wondered how electric basses make sounds in the first place? It’s a fascinating process and the most important part of your electric guitar’s plugged-in tone. Below is a simple explanation:

- Guitar strings are made out of a magnetic metal.

- Underneath the strings sits the ‘pick up’ which is fitted into the body of the guitar.

- The pick up consists of a coil of wire wrapped around a magnetic pole piece (or pieces).

- When you pluck/hit a string – it vibrates which generates a voltage in the coil.

- In a passive bass (more of this later), the pickup(s) are directly connected to volume and tone controls which are then sent to the output of the instrument.

The signal chain

The signal chain is the order in which you place any effects/pedals. At first, I put my tuner first in the chain after the bass guitar the signal can be easily muted for silent tuning.

The pre-amp

This electronic device amplifies a weak signal, such as that from a passive bass.

These are found in bass/guitar amplifiers, studio mixing consoles, domestic HiFis, sometimes within the bass itself (referred to as an active bass) and as external units in the format of a pedal.

There are many different specifications but some are capable of driving a power amplifier (the second stage which amplifies this intermediate signal level to one which can drive a loudspeaker) and/or can be used before the amplifier to modify the sound, volume and tone of the instrument – I will explain more about this in the next instalment.

This brings me to the third pedal I owned.

Lehle RMI BassSwitch IQ DI

Photo credit: Simon Campbell

The Lehle RMI BassSwitch IQ DI was the centrepiece of my first pedalboard (a metal frame where all the pedals are organised). It was exactly what I needed at the time to help me sort out the technical challenges of playing two different basses with different sounds and volumes

The unit had two channels with separate volume controls enabling me to set the level for each bass by using a foot switch to select channel A or B.

Channel B also has very natural sounding tone controls (or equalisation – EQ) which allowed me to change the tone of the bass in channel B to complement the bass in channel A.

Two effects loops

The unit also has two effects (FX) loops, one switchable and one in all the time for both channels. In the switchable loop, I placed the FUZZ (so I could switch it in and out using the button on the Lehle) and my rarely used Ernie Ball volume pedal in the unswitched.

If you want to see the possibilities of routing and an explanation of FX loops, check out the manual.

The all-important mute switch

My tuner is connected to a dedicated ‘tuner output’ and the Lehle’s output can be muted via another footswitch.

As I mentioned at the beginning of the article, this mute is critical which enables me to tune up between songs silently as there’s nothing worse than someone audibly tuning up on stage – it’s messy and unprofessional.

The Direct Inject output

There are two outputs from the Lehle, one for the amplifier plus a very high-quality Direct Inject (DI) output which is compatible with mixing consoles, allowing the sound engineer to take the signals right from your pedals before they get to the amplifier.

My bass tone comes from the amplifier and speaker cabinet combination and I always insist it’s miked up for a performance.

There are some instances however that you need the signal to be sent to the live sound system (PA). For example, my Fylde King John acoustic bass is better using this direct method rather than going through the stage amplifier and again, more of this in the next edition!

It is a high-quality piece of kit that you come to expect from Lehle (although now sadly discontinued) and has never let me down. The only thing I have to watch out for is operator error when I’m wearing my big kickass ‘Boots of Rock’.

And finally…

I hope you enjoyed this article – if you have any questions or feedback, it would be cool to hear from you.

Next up in Walking the Bass Line – I’ll talk a little more about the role of the bass guitar, amplifiers, cabinets and another pedal.

British-born Suzy Starlite is a multifaceted artist known for her work as a bassist, singer, multi-instrumentalist, composer and multimedia artist. She co-owns Supertone, an independent record label and vintage analogue recording studio with her husband, guitarist and music producer Simon Campbell, based near Lisbon, Portugal. Their band, Starlite & Campbell, has released six studio albums and two live albums to date. Visit online at starlite-campbell.com/suzy-starlite, vibes.starlite-campbell.com/ and youtube.com/@starlitecampbell

Bass Edu

BASS LINES: Triads & Inversions Part II

BASS LINES: Triads & Inversions Part II

Hello bass players and bass fans! In this issue, we are going to study the triads and their inversions.

In the last lesson, we were studying triads in their fundamental position. This time, we are going to study what is known as the first inversion of the triads.

The first inversion consists of the third going on the bass in the triad, as we will see below:

C Major Triad (1st inversion)

E – G – B

C Minor Triad (1st inversion)

Eb – G – B

C Diminished Triad (1st inversion)

Eb – Gb – C

C Augmented Triad (1st inversion)

E – G# – C

See you next month for Part III… GROOVE ON!!!

Bass Edu

Approach Notes – Part 6

Approach Notes – Part 6

As we move into lesson six of approach notes applied to chord tones, it’s important to go back and review the previous approaches. The constant review and application of these concepts will add a layer of chromaticism to both your bass lines and solos. The approaches need to be burned into your long term/ permanent memory for them to come out in your playing.

This first example approaches a third inversion of a G major 7th arpeggio.

A single chromatic approach from below and a double chromatic approach from above approaches the 7th, continue to the root, 3rd, 5th, single from below and double chromatic from above to the 7th, continue to the root, 3rd, and back down.

The next example approaches the G major arpeggio in root position.

The next example approaches the root of a G major 7th arpeggio as a single chromatic from below and a double chromatic approach from above -before continuing to the third, fifth, seventh, single chromatic from below/ double from above to the root, continue to the third, fifth, and come back down.

The next example approaches the first inversion of G major 7th arpeggio.

A single chromatic from below/ double from above approaches the third, continue to the fifth, seventh, root, single chromatic from below/ double from above to the third, continue up to the fifth and seventh, and back down.

The third example approaches a second inversion of a G major arpeggio.

A single chromatic from below/ double from above approaches the fifth, continue to the 7th, root, 3rd, single from above/ double from below to the 5th, continue to the 7th, root, and back down.

After studying these various approach notes, you will begin to recognize the concepts utilized in your favorite solos. Continue the journey and good luck!

Bass Edu

BASS LINES: Triads & Inversions Part I

Triads & Inversions Part I…

Hello bass players and bass fans! In this issue, we are going to study the triads and their inversions.

It is very important for all bassists to understand and master the triads, but it is even more important to understand their different inversions.

In Part I, we are going to learn what the triad is in fundamental position.

The Formula consists of root, third and fifth.

Degrees of the Triad

Major Triad: 1 – 3 – 5

Minor Triad: 1 – b3 – 5

Diminished Triad: 1 – b3 – b5

Augmented Triad: 1 – 3 – #5

Fig.1 – The C, Cm, Cdim & Caug triads

(Fundamental Position)