Features

In Depth Interview With Bassist Mike Pope

“Mike Pope is a real renaissance man. He is a musician of broad scope and tremendous talent. His virtuosity on electric bass and acoustic bass is rare even by today’s standards”.

Victor Wooten has commented, “If I were going to study improvisation at this point, I’d do it with Mike Pope.”

After two solo CD’s and countless tours, we find there’s still much more to come.

Jake: You’ve received many accolades from noted players, especially for your improvisational skills. Could you give me a brief synopsis of what you’ve focused on as far as soloing goes?

Mike: I guess a brief synopsis would be that I’ve spent most of my time trying to figure out how to play what I want to play. I haven’t spent a lot of time figuring out what to play. Most of the time someone will say I want to learn theory, or I want to learn how to solo more, and it’s a waste. It’s enough of a challenge to try to figure out how to get the music that’s in you, out of you, as far as I’m concerned. So that’s been my focus, maybe not consciously, but that’s it. And in retrospect, everything I’ve done goes to that end.

Jake: I find when I talk to players of your caliber, that I’m always interested in the “how”.

Mike: How to get to any place that’s yours…. well…. obviously there’s a lot of luck and chance involved in any of it, there really is.

Let me put it this way. Lets take two guys that practice like crazy until their 25 years old, and one guy goes out and starts working with a bunch of heavy people and gets tons of experience, and goes out and plays, and the other guy spends just as much time at home practicing, working on what he wants to work on. The guy who’s out there playing is going to get better, and those are the breaks.

There’s a thing that happens when you’re out playing in real life with different people that you can’t simulate at home. So when you are hearing about this guy that doesn’t play with anybody, but he’s “as good” as all these other great guys, I’d almost never believe that for a moment.

There’s something about being out there and playing with all the great guys that makes that group of players better. It’s purely a skill level thing. There are lots of people with tons of talent, but that doesn’t mean anything. Talent doesn’t get you anything. Skill makes you able to do what you do. Even if you’re a very talented guy, you can’t rest on those laurels.

Jake: I understand your point. You did a tour with Al Dimeola a while back. I know Anthony Jackson held that chair for a while, so I’m going to guess it was a rough book.

Mike: No, it really wasn’t. He called me for that date two days before the first gig, and I drove to his house that night and pretty much read through everything. It was hard, but it wasn’t crazy. I was off the book in a few weeks and had everything memorized. There were a lot of lines, but nothing a pianist or a violinist wouldn’t have down quickly.

Jake: What have you done that “has” been a challenging book for you?

Mike: The Chick (Corea) book was highly challenging. Probably the most challenging book I ever played was with Roland Vasquez, and that was a book that was written for Anthony basically. He’s a drummer, and an interesting writer, and everything was super complex–complex to the max man, a major butt-kicking book.

Jake: So what would you suggest that a player have under his belt to handle, and be able to actually compliment a book like that?

Mike: There are not many bass players that could handle and compliment a book like Rolands. Understand, that book is an anomaly; it’s almost harder than it needs to be sometimes. In spite of the fact that the bass player should be about pocket and groove, and part of the whole, at the same time if that’s all your focused on, your probably not going to be able to play a book like that.

There’s a lot more to music than just what a bass player does, and of course in this day and age, what’s required of a bass player is becoming more difficult because there’s more and more people out there that can do material that’s not that easy to do.

I think one of the real keys is to extend beyond the bass, beyond what its normal parameters are. You should set your own parameters of what the instrument should do. You can practice and do what Pattituci did, a lot of legit cello material on bass, that certainly gets you around the instrument really well. But at the end of the day, it has more to do with how you approach the instrument in general as opposed to what you practice. It isn’t about your hands quite so much as about how you approach the instrument, how you perceive it, and how you see yourself playing it.

Jake: I know you’re fairly proficient on piano as well. I’m guessing that’s been helpful, and has impacted your bass playing to a degree.

Mike: It’s been incredibly helpful. I can’t think of anything that’s more helpful to my bass playing, other than my bass playing. It’s a whole completely different perspective, and I continue to learn more and more as I play and challenge myself more and more.

The thing is, there’s a lot more pedagogical material out there for the piano than the bass, especially the electric bass. There’s a lot, a lot, a lot more out there, and if you go back and look at the European piano tradition, you can see what those people are capable of playing. I’m talking about the great pianists of all time, the Rachmaninoff’s, etc., and in more modern times, players like Vladimir Horowitz. The things that these people were capable of on their instruments make everything that every electric bass player ever did look like a joke.

The level of ability on their instruments, and what they’ve archived, has shown that what we have done on bass has not even scratched the surface yet of what can be done. I probably won’t be the guy to take it there, but you know, there are guys going in that direction. Victor Wooten, Matt Garrison, and Jeff Berlin are all very accomplished technicians, and look hard at the traditional approach of the instrument.

If you look at the body of work that’s out there to support the piano or the violin, and the traditions that have been established in Europe on how to play these instruments, there’s nothing even remotely close to that out there for electric bass at this point. There will be I’m sure, but not now.

Lets take something that doesn’t really get talked about too much, the mental process of playing on any instrument. There has been a lot of research on this. One of the most significant books that was written on this was written by a guy named Arnold Schultz. He was a piano teacher in Chicago, and he was actually my father’s piano teacher. He wrote a book called “The Will of a Pianists Finger”. It talks all about the mechanics of playing the piano, and also about the mental process of playing the piano.

One of the most revealing points that I got from this book was, you really don’t have direct conscious control over what your muscles do, and as long as you think that you do, then you’ll never get it. Any movement that your body makes is not under a conscious system. If you’re trying to directly control movements, you’ll do a very poor job of it, and you’ll have a lot of problems being consistent and accurate. It’s more a matter of willing things to happen and learning how to train your motor nervous system. A lot of people call it muscle memory, which it isn’t because muscles don’t remember anything. That term is a complete misnomer. What they mean is motor learning, and that does not take place in the muscles, it takes place in the brain and in the nervous system.

It all has to do with the way the motor system coordinates a complex set of movements. You have to understand how to teach it. Your motor nervous system learns exclusively, not inclusively. As a baby, you don’t start off not moving, then learn to move what you need, you start off moving in a very uncoordinated and uncontrolled way and as you repeat steps of movements that you want to achieve, you learn to do away with the movements that don’t have anything to do with what your trying to get done. And learning to play an instrument is the same way. It happens through repetition, and this isn’t a matter of opinion, its just physiology. It’s very simple and it’s all very documented, and it’s all very true.

But I think a lot of people out there like to jump on the fact that this means that we don’t have control over what we’re doing, and it’s wrong, we do. It’s a different kind of control.

There are people that call it ‘getting into the zone’, or ‘getting into a certain kind of vibe’, whatever, but the truth is and what really happens when you’re there is that it’s sort of a nervous coordination. It’s when all your systems are operating. You’ve got your conscious mind which is kind of your conductor, and it’s delegating all these instructions to the motor nervous system, and the nervous system is dealing with what it takes to get it done, because it’s set up to be able to do it in a highly proficient and precise way. As soon as you start trying to rap the conscious mind around that in the middle of a set of movements, like I’m going to make my 3rd finger go here, that just screws the whole thing up. It’s a lot more complex than that, but that’s sort of the general thing of it, and I’ll tell you man, this is the stuff that really great classical pianists have known about for years. It’s where most of the great ones are coming from.

But it hasn’t quite made it to the word of modern music, particularly improvisational music, and that has something to do with the fact that improvisatory music has this whole other set of mental processes that are actually thinking, what the hell do I want to play?

It’s not a matter of learning a piece, and training your hands, it’s also another component, but it still applies…. its harder, a lot harder actually. It’s a concept, I guess, that in today’s context is in its infancy. A lot of people understand it in their own way, and obviously there’s someone you can go to and listen to and realize that they understand it, and it’s the way it lets them play there asses off, you know what I mean… They always get it, but they’re not necessarily getting it other than just the way that it applies to them.

I think it’s a concept that applies to everybody in some way. It’s like a variable absolute if that makes any sense. You’ve got an absolute right way to play, and an absolute right way to think, period. In order to get your musical impetuous across, there is an absolute right way to play. You can’t say well, this is how I like to do it, or this is how it feels right to me, ultimately there’s an absolute, but there’s a variability in who it is that the absolute applies to. For this guy, there’s an absolute, and it’s up to him to find it. You can learn it, and you can key it to happen every single time. But I think a lot of people would just sort of leave it up to chance. Fortunately, a lot of times it works out, but a lot of times it doesn’t.

Jake: Understanding that each individual will react, or shall I say hear your thoughts on this differently, how much of this might you present to a student—what would you have them try to play?

Mike: There are exercises that I’ve done with people that I can get them to grasp onto right away. If I can find something that somebody’s having trouble playing, or trouble playing up to tempo, I just sit down with them and ask them to play it, and ask them to concentrate on what they’re doing…. this is what I want to play, and I’m not going to concern myself with how to play it, I’m going to focus on what to play. Actually it’s a small thing, but it makes a difference because it establishes a little bit of a disconnect between your conscious thinking, and what your physically trying to do. This is a disconnect that you want.

You don’t want to be forcing yourself to be playing it a certain way so much, and you can still teach yourself to play it a certain way if you work on that… do you know what I mean? You’ve got to establish that sensation of a disconnect between the conscious thing and the motor nervous thing. Think about how many complex movements are involved with standing up, walking into the bathroom and blowing your nose. There are an incredible number of very fine motor skills involved with that.

It comes naturally to us because it’s all part of everyday life for us, and it has been since we’ve been little kids. But if you thought about trying to actually, consciously make every one of those movements happen, there’s no way, that’s crazy, it could never happen. And the point is that the physical act of playing music is the same situation.

Jake: Final question here. You’ve mentioned that you’re about to finish building your studio, and have plans after that to start recording. What do you plan to put together for your next CD?

Mike: I’ll keep this short — I could make a long answer to this also, but I won’t. The short version is I’m going to do a Mike Pope record, and not try to make it into anything in particular, or try to necessarily conform to any sort of rules and regulations in terms of how records are supposed to be done. I’ve got a lot of material and some really cool ideas. I’m going to play a lot of electric and a lot of acoustic. There will be more bass on this album than the last two, in the sense that I will be a little more present melodically, and I’m going to play a lot of piano on it as well.

Jake: I’m sure it will be great having your own studio.

Mike: I’ll leave you with one point that will probably be helpful to people. If your thinking about spending money and making a record, it makes a lot more sense when you look at what it costs to make a record, and what it costs to promote a record, to consider taking that money and investing it into recording gear. The costs add up if it’s not on your own gear, and the likelihood of making anything on this is virtually nothing. Even the major artists generally don’t make that much money.

So if you invest in your own record, and cost out what that would be over several records, the records become a lot more economical number one, and number two, you can really put out a body of material. I really think that’s important to have more than a record or two out there. Keep throwing stuff out into the market even if it doesn’t get promoted heavily, because eventually, you’ve got 5, 6, 8, or 10 records out there, and then you start a little promotion push, then you can kind of promote everything all at once. It takes a while to get there, but in my opinion it’s the only thing to sort of do to promote a solo name.

You really need to have a lot of stuff out there. That’s where I’m kind of going to get this record made–get the studio built and at least make a record a year. That’s more or less the idea.

Jake: I’m looking forward to hearing it.

Mike: Thanks

Visit Mike Pope online at www.mikepopejazz.com

Features

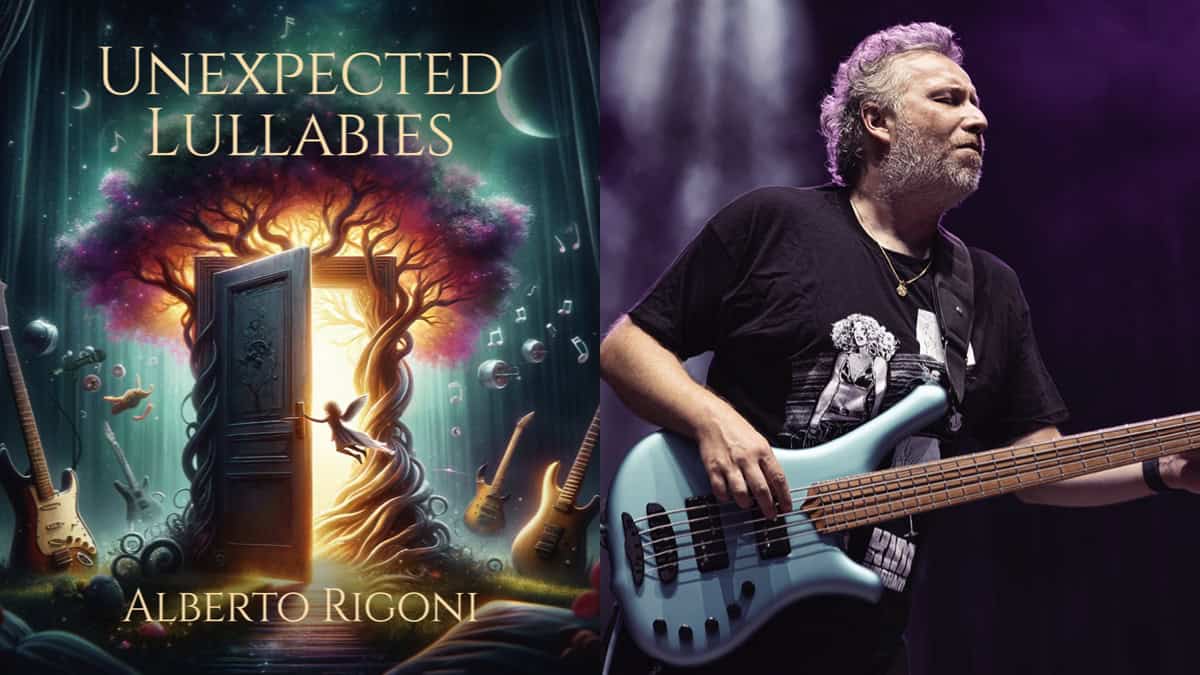

Alberto Rigoni On Unexpected Lullabies

Readers have been fans of the composer, bass player, and Bass Musician contributor Alberto Rigoni for some time now.

In this interview, we had the opportunity to hear directly from Alberto about his love of music and a project near and dear to his heart, “Unexpected Lullabies”…

Could you tell our readers what makes your band different from other artists?

In 2005, I felt the urge to write original music. My first track was “Trying to Forget,” an instrumental piece with multiple bass layers (rhythm, solo, and arrangement), similar to the Twin Peaks soundtrack. When I played it for a few people, they really liked it, and I decided to continue composing based on my instinct and ear without adhering to any specific genre. In 2007, I released “Something Different” with Lion Music. The title says it all! Since then, I’ve released many solo albums, each different from the others, ranging from ambient to prog, fusion, jazz, and new age. I am very eclectic!

How did you get involved in this crazy world of music?

As a child, I listened to the music my parents enjoyed: my dad loved classical music, while my mom was into Pink Floyd, Genesis, Duran Duran, etc. These influences left a significant mark on my life. However, the turning point came at 15 when a drummer friend played me “A Change of Seasons” by Dream Theater, which was a shock! From that moment, I decided to play bass and cover Dream Theater songs, which I did for many years with my cover band, Ascra, until it disbanded in 2004. After that, I joined TwinSpirits (prog rock) led by multi-instrumentalist Daniele Liverani. Since then, I haven’t played any more covers!

Who are your musical inspirations, and what inspired the album and the songs?

My roots are in progressive rock metal, with influences from bands like Dream Theater, Symphony X, and many others. However, I listen to all genres and try to keep an open mind, which helps me compose original music. On bass, I was significantly inspired by Michael Manring and Randy Coven (bassist of Ark, Steve Vai, etc.). But I don’t have a real idol; I just follow my own path without compromise.

What are your interests outside of music?

Living in Italy, I love good food and wine! Beyond that, I have a deep interest in art in general and history, not just of my country. I enjoy spending time with friends, skiing, biking, and walking in nature. This is how I spend my free time. The rest of my time is devoted to music and my family!

Tell us about the new album.

It is definitely an out-of-the-box album. When I found out last year that I was going to have a baby girl, I decided to compose a sort of lullaby album, but I didn’t want to cover already famous lullabies. So, I started composing new tunes with the goal of creating an album that was half-sweet and half-hard rock. I did include some covers like “Strangers in the Night” by Frank Sinatra, sung by Goran Edman, former lead singer of Malmsteen. It’s not exactly a lullaby, but I felt the lyrics fit the album, as does the instrumental version of “Fly Me to The Moon.” There are also tracks with just bass and piano (Nenia) or two basses (Vicky). It was definitely an interesting creative process!

What is the difference between the new album and your previous releases, and will there be any new material from your other outfit called BAD AS?

BAD AS is essentially a metal band with several influences including prog. My solo genre is quite different, although there are some metal songs on a few albums. It’s always difficult for me to categorize my music… let’s say it’s a mix of prog, ambient, fusion, and new age.

Where was the album recorded, who produced it, and how long did the process take?

I produced my last album entirely by myself, including mixing and mastering. Unlike other albums I’ve produced within a few months, this one took much longer, perhaps because I was very busy or maybe because I wanted it to be perfect for my daughter, who is now three months old. In any case, I am satisfied. Once again, I did something different from my previous albums.

What is the highlight of the album for you and why?

My favorite song is the first track titled “Vittoria,” named after my daughter. It’s the intro to the record and isn’t very long, but the melody stuck in my head. Another standout track is the instrumental version of “Fly Me to The Moon” by Frank Sinatra, where I used fretless bass. The first part is sweet, the second part definitely rocks!

How are the live shows going, and what are you and the band hoping to achieve?

With BAD AS, this year we shared the stage with David Ellefson’s (former Megadeth bassist) band and talented young singer Dino Jelusik (White Snake). We plan to continue performing all over Europe!

What’s in store for the future?

I am working on an instrumental project called Nemesis Call, a progressive shred prog metal album with various influences. It will feature guest appearances from famous musicians like drummers Mike Terrana and Thomas Lang, as well as young talents like Japanese guitarist Keiji from Zero (19), 14-year-old Indian drummer Sajan Young, and guitarists Alexandra Zerner and Alexandra Lioness, Hellena Pandora. It’s scheduled for release at the end of the year or early 2025. As an independent artist, I have launched a fundraising campaign with exclusive pledges at www.albertorigoni.net/nemesiscall. And no, I am not begging; the album will be released anyway!

What formats is the release available in?

Unexpected Lullabies is available both as a Digipack CD and on streaming platforms.

What is the official album release date?

June 4th, 2024.

Thanks for this interview Bass Musician Magazine and for the continued support to my career!

Visit Online:

www.albertorigoni.net

www.youtube.com/albertorigoni

albertorigoni.bandcamp.com

www.instagram.com/albertorigonibassplayer

www.facebook.com/albertorigonimusic

www.tiktok.com/@albertorigonibassist

CD Track Listing:

1. Vittoria

2. Fly Me to the Moon

3. Azzurra

4. Dancing with Tears in My Eyes (feat. John Jeff Touch)

5. Out of Fear

6. Veni Laeatitia (feat. Alexandra Zerner)

7. Nenia

8. Slap Lullaby (feat. Karl Clews)

9. Saga

10. Vicky (feat. Michael Manring)

11. Ocean Travelers (feat. Vitalij Kuprij)

12. Strangers in the Night (feat. Göran Edman)

13. Peaceful

14. Un uomo che voga (feat. Eleonora Damiano)

Band Line-Up:

- Tommaso Ermolli arrangements on “Vittoria”

- Sefi Carmel on “Fly Me to the Moon” (Cover) (except for the keyboard solo by Alessandro Bertoni)

- Piano and keyboards by Alessandro Bertoni on “Azzurra”

- Leonardo Caverzan, guitars, and John Jeff Touch, vocals on “Dancing with Tears in my Eyes” (Cover)

- T. Ermolli keys on “Out of Fear”

- Alexandra Zerner everything on “Veni Laetitia”

- Daniele Bof piano on “Nenia”

- Karl Clews, piccolo bass on “Slap Lullaby”

- Jonas Erixon vocals and guitars on “Saga”

- Michael Manring bass on “Vicky”

- Vitalij Kuprij, keyboards and piano, and Josh Sapna, guitars, on “Ocean Traveler”

- Göran Edman, vocals, Emiliano Tessitore, guitars, Emiliano Bonini, drums, on “Strangers in the Night” (Cover) everything by Alberto Rigoni and vocals by Federica “Faith”

- Sciamanna on “Peaceful”

- T. Ermolli, guitars, and Eleonora Damiano, vocals, on “Un uomo che voga All drums programmed by Alberto Rigoni

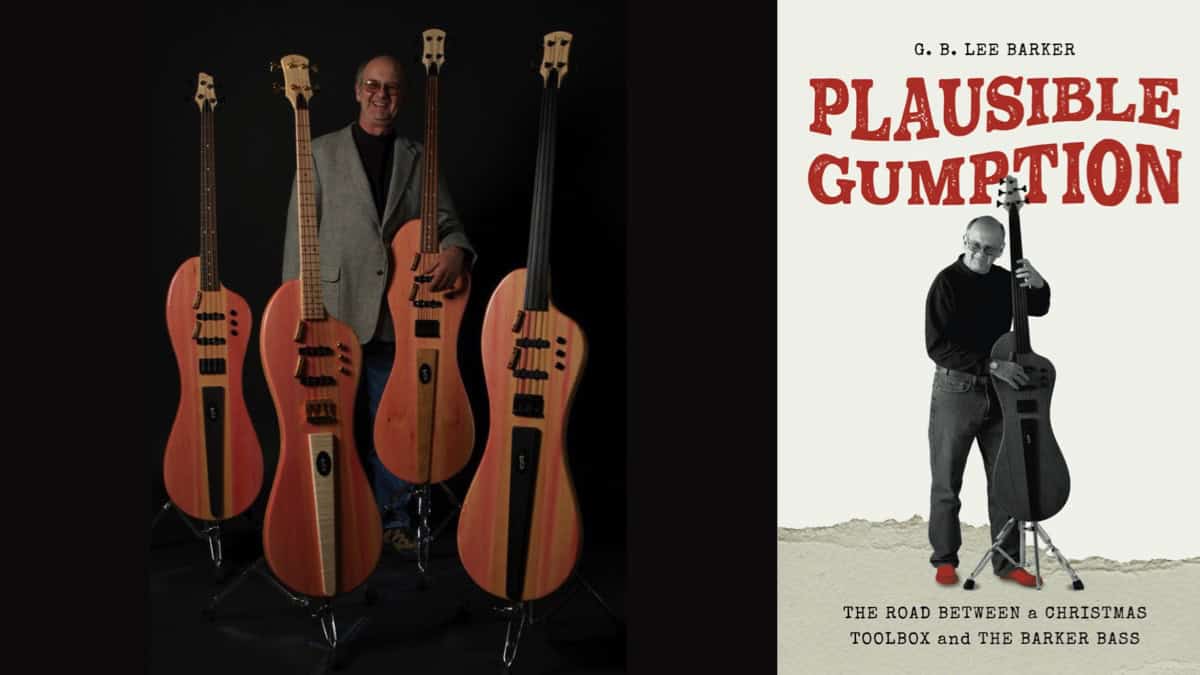

Bass Books

Interview With Barker Bass’s Inventor and Writer Lee Barker

If you are an electric bass player, this is an exciting time to be alive as this relatively new instrument evolves around us. Some creative individuals have taken an active role in this evolution and made giant leaps in their own direction. Lee Barker is one of these inventive people having created the Barker Bass.

Fortunately, Lee is also an excellent writer (among so many talents) and has recently released his book “Plausible Gumption, The Road Between a Christmas Toolbox and The Barker Bass”. This book is a very fun read for everyone and shares a ton of details about Lee’s life in general, his experiences as a musician, a radio host, and a luthier. Now I am fortunate to have the great opportunity to gain even more insights into this renaissance man with this video interview.

Plausible Gumption, The Road Between a Christmas Toolbox and The Barker Bass is available online at Amazon.com

Features

Bergantino Welcomes Michael Byrnes to Their Family of Artists

Interview and photo courtesy of Holly Bergantino of Bergantino Audio Systems

With an expansive live show and touring, Mt. Joy bassist Michael Byrnes shares his experiences with the joyful, high-energy band!

Michael Byrnes has kept quite a busy touring schedule for the past few years with his band, Mt. Joy. With a philosophy of trial and error, he’s developed quite the routines for touring, learning musical instruments, and finding the right sound. While on the road, we were fortunate to have him share his thoughts on his music, history, and path as a musician/composer.

Let’s start from the very beginning, like all good stories. What first drew

you to music as well as the bass?

My parents required my sister and I to play an instrument. I started on piano and really didn’t like it so when I wanted to quit my parents made me switch to another instrument and I chose drums. Then as I got older and started forming bands there were never any bass players. When I turned 17 I bought a bass and started getting lessons. I think with drums I loved music and I loved the idea of playing music but when I started playing bass I really got lost in it. I was completely hooked.

Can you tell us where you learned about music, singing, and composing?

A bit from teachers and school but honestly I learned the most from just going out and trying it. I still feel like most of the time I don’t know what I am doing but I do know that if I try things I will learn.

What other instruments do you play?

A bit of drums but that’s it. For composing I play a lot of things but I fake it till I make and what I can’t fake I will ask a friend!

I know you are also a composer for film and video. Can you share more

about this with us?

Pretty new to it at the moment. It is weirdly similar to the role of a bass player in the band. You are using music to emphasize and lift up the storyline. Which I feel I do with the bass in a band setting. Kind of putting my efforts into lifting the song and the other musicians on it.

Everybody loves talking about gear. How do you achieve your “fat” sound?

I just tinker till it’s fat lol. Right now solid-state amps have been helping me get there a little quicker than tube amps. That’s why I have been using the Bergantino Forté HP2 – Otherwise I have to say the cliche because it is true…. It’s in the hands.

Describe your playing style(s), tone, strengths and/or areas that you’d like

to explore on the bass.

I like to think of myself as a pretty catchy bass player. I need to ask my bandmates to confirm! But I think when improvising and writing bass parts I always am trying to sneak little earworms into the music. I want to explore 5-string more!

Who are your influences?

I can’t not mention James Jamerson. Where would any of us be if it wasn’t for him? A lesser-known bassist who had a huge effect on me is Ben Kenney. He is the second bassist in the band Incubus and his playing on the Crow Left the Murder album completely opened me up to the type of bass playing I aspire towards. When I first started playing I was really just listening to a lot of virtuosic bassists. I was loving that but I couldn’t see myself realistically playing like that. It wasn’t from a place of self-doubt I just deep down knew that wasn’t me. Ben has no problem shredding but I was struck by how much he would influence the song through smaller movements and reharmonizing underneath the band. His playing isn’t really in your face but from within the music, he could move mountains. That’s how I want to play.

What was the first bass you had? Do you still have it?

A MIM Fender Jazz and I do still have it. It’s in my studio as we speak. I rarely use it these days but I would never get rid of it.

(Every bass player’s favorite part of an interview and a read!) Tell us about

your favorite bass or basses. 🙂

I guess I would need to say that MIM Jazz bass even though I don’t play it much. I feel connected to that one. Otherwise, I have been playing lots of great amazing basses through the years. I have a Serek that I always have with me on the road (shout out Jake). Also have a 70’s Mustang that 8 times out of 10 times is what I use on recordings. Otherwise, I am always switching it up. I find that after a while the road I just cycle basses in and out. Even if I cycle out a P bass for another P bass.

What led you to Bergantino Audio Systems?

My friend and former roommate Edison is a monster bassist and he would gig with a cab of yours all the time years ago. Then when I was shopping for a solid state amp the Bergantino Forté HP2 kept popping up. Then I saw Justin Meldal Johnsen using it on tour with St. Vincent and I thought alright I’ll give it a try!

Can you share a little bit with us about your experience with the Bergantino

forte HP amplifier? I know you had this out on tour in 2023 and I am pretty

certain the forte HP has been to more countries than I have.

It has been great! I had been touring with a 70’s SVT which was great but from room to room, it was a little inconsistent. I really was picky with the type of power that we had on stage. After a while, I thought maybe it is time to just retire this to the studio. So I got that Forte because I had heard that it isn’t too far of a leap from a tube amp tone-wise. Plus I knew our crew would be much happier loading a small solid state amp over against the 60 lbs of SVT. It has sounded great and has really remained pretty much the same from night to night. Sometimes I catch myself hitting the bright switch depending on the room and occasionally I will use the drive on it.

You have recently added the new Berg NXT410-C speaker cabinet to your

arsenal. Thoughts so far?

It has sounded great in the studio. I haven’t gotten a chance to take it on the road with us but I am excited to put it through the paces!

You have been touring like a madman all over the world for the past few

years. Any touring advice for other musicians/bass players? And can I go to Dublin, Ireland with you all??

Exercise! That’s probably the number one thing I can say. Exercise is what keeps me sane on the road and helps me regulate the ups and downs of it. Please come to Dublin! I can put you on the guest list!

It’s a cool story on how the Mt. Joy band has grown so quickly! Tell us

more about Mt. Joy, how it started, where the name comes from, who the

members are and a little bit about this great group?

Our singer and guitarist knew each other in high school and have made music together off and on since. Once they both found themselves living in LA they decided to record a couple songs and put out a Craigslist ad looking for a bassist. At the time I had just moved to LA and was looking for anyone to play with. We linked up and we recorded what would become the first Mt. Joy songs in my house with my friend Caleb producing. Caleb has since produced our third album and is working on our fourth with us now. Once those songs came out we needed to form a full band to be able to do live shows. I knew our drummer from gigging around LA and a mutual friend of all of us recommended Jackie. From then on we’ve been on the road and in the studio. Even through Covid.

Describe the music style of Mt. Joy for me.

Folk Rock with Jam influences

What are your favorite songs to perform?

Always changing but right now it is ‘Let Loose’

What else do you love to do besides bass?

Exercise!

I always throw in a question about food. What is your favorite food?

I love a good chocolate croissant.

Follow Michael Byrnes:

Instagram: @mikeyblaster

Follow Mt. Joy Band:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/mtjoyband

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/mtjoyband

Bass Videos

Artist Update With Mark Egan, Cross Currents

I am sure many of you are very familiar with Mark Egan as we have been following him and his music for many years now. The last time we chatted was in 2020.

Mark teamed up with drummer Shawn Pelton and guitarist Shane Theriot to produce a new album, “Cross Currents” released on March 8th, 2024. I have been listening to this album in its entirety and it is simply superb (See my review).

Now, I am excited to hear about this project from Mark himself and share this conversation with our bass community in Bass Musician Magazine.

Photo courtesy of Mark Egan

Visit Online:

markegan.com

markegan.bandcamp.com

Apple Music

Amazon Music

Bass Videos

Interview With By the Thousands Bassist Adam Sullivan

Bassist Adam Sullivan…

Hailing from Minnesota since 2012, By the Thousands has produced some serious Technical Metal/Deathcore music. Following their recent EP “The Decent”s release, I have the great opportunity to chat with bassist Adam Sullivan.

Join me as we hear about Adam’s musical Journey, his Influences, how he gets his sound, and the band’s plans for the future

Photo, Laura Baker

Featured Videos:

Follow On Social

IG &FB @bythethousands

YTB @BytheThousands