Features

Tapping into Impermanence, A Discussion with Bassist John Ferrara

All photos provided courtesy of John Ferrara, with Photographer credits, where applicable.

Bassist John Ferrara…

I first became aware of John Ferrara while covering the Felix Martin show at the James Street Tavern in Pittsburgh, PA on March 8, 2017. Ferrara’s band, Consider the Source, was touring with Martin at the time and, during their set, I heard something that really took me aback. It was clear that it was a bass solo, but none like I’d ever heard before. As much of a bass fan as I am, my idea of a bass solo was something you’d hear at jazz concerts or perhaps Cliff Burton’s “(Anesthesia)-Pulling Teeth” from Metallica’s Kill ‘Em All. This was entirely different. It was an amalgam of funk, fusion, prog and jazz, rhythmic at times, melodic at others. Parts were brutally fast and raucous, intertwined with sections that were moody and ethereal. I was awestruck by what I saw and heard, completely mesmerized. That was my introduction to John Ferrara and his definition of bass playing. From that moment, I knew I wanted to talk with Ferrara about what motivated him to hone his playing skills to such a high level, to become a true overachiever on his instrument. My first discussion with him was incorporated into a motivation and achievement piece I did a year or so ago, not long after the release of Ferrara’s solo debut, A Harmony of Opposites. Several recurring themes became apparent during that first conversation, one of which was Ferrara’s dedication to excellence and continuous improvement. Another was him finding a very positive, therapeutic outlet in his music, a way to express whatever he’s feeling and share it with others. With Ferrara’s sophomore solo record, A Lesson in Impermanence, set for release on March 11, 2022, I was curious to learn how those themes and others he and I discussed impacted his writing process and shaped the new material.

We kicked off our discussion talking about how his solo work compares to that which he creates as a member of Consider the Source or when collaborating with other artists, such as Seth Moutal. Ferrara explained that performing in a solo environment is much different than when he’s with a full band. Consider the Source plays larger venues to bigger audiences and the crowd tends to have a party-type mood, a mood sometimes magnified by various substances. Ferrara is quick to exclaim, “I’m not judging any of that. It’s a good outlet and gives people an opportunity to relax and enjoy themselves. But that environment creates a natural barrier between the audience and the band even when a physical barrier doesn’t exist. Everyone is in their own space and you don’t feel as connected.”

Ferrara is closer with his audience as a solo performer, in proximity and perhaps emotionally. Though he didn’t use this word, everything he expressed suggests that he finds performing as a solo artist to be a more intimate, one-on-one experience and, as such, it shapes what material he chooses to play in that setting. He explained, “I don’t write intending for songs to be solo material or end up on a Consider the Source record. I just write and afterward think, ‘Where does that fit best?’” He told me that his writing process is very fluid and organic, that he doesn’t necessarily write songs, but rather, he allows them to develop and evolve in whatever manner they naturally want to go. Ferrara gave the example of Junji Ito, a writer of Japanese Manga, horror comics, in particular. Ferrara told me that Junji once explained that he was writing about a character the plot for whom he’d already planned out. But as he was writing, he came to realize that wasn’t where the character wanted to go, so he changed the plot and allowed the character to grow and develop organically. “That’s the way I write songs. I don’t set out to write in any particular style or using a specific method. I just play and write and allow the song to evolve the way it wants to,” Ferrara said.

Listening to his latest release or any of his material for that matter and watching him perform makes it clear that Ferrara finds music to be a powerful vehicle for emotional expression. As he explained in our first conversation, it’s something that allows him to share whatever he’s feeling be it positive or negative and, afterward, he’s got something to show for it. At its very core, Ferrara says, “It’s cathartic.” With that in mind, I was curious about how his second record played into the grand scheme of Ferrara’s musical vision. Is A Lesson in Impermanence a continuation of the first record, an evolution of the original theme or is it something wholly different? How does the new material integrate into his overall message and vision?

Ferrara reiterated that he doesn’t write with any particular intention or try to force the music. “Be that as it may,” he offered, “I guess the second album does represent the evolution of my music and of me. Even without trying, it demonstrates where I’ve been and where I’m headed along the journey and it kind of freezes time at this fork in the road. Here’s where I am right now. I wrote A Lesson in Impermanence during the Covid pandemic and writing it definitely got me through some difficult times. It also saw me through positive transitions, such as my move to Rhode Island to be with my girlfriend, Emily.”

We went on to discuss the meaning of the record’s title and what went into naming a few of its tracks. Ferrara explained that the album’s title comes from the Eastern ideal of impermanence. “Coming to terms with change and learning to adapt to it is essential and never has that been more clear than during the pandemic. We’ve all had to make lots of changes and adapt to what we’ve termed, ‘the new normal.’ The sooner we learn to accept the impermanence of things and find ways to adapt to whatever is happening around us, the better off and more at peace we’ll be,” Ferrara said. He went on to tell me that the album tracks’ names are inspired by a variety of different things, including television shows, which was the case for the song “Just Don’t Look.”

‘That song takes its name from the Treehouse of Horror VI episode of the Simpsons wherein Springfield’s billboard characters come to life and terrorize the town,” Ferrara told me. “In that episode, the solution to the problem was quite literally ‘just don’t look’ and the monsters will go away. That’s where my song gets its name, but it goes further than that. Just don’t look has a metaphorical meaning as it relates to our society and the monsters wreaking havoc and causing destruction in our day-to-day lives, things such as social media and the news. As simple as the solution was, ‘just don’t look’ worked in that episode of the Simpsons and it remains a good approach. Social media is part of our lives and can be of great benefit, but we need to use it wisely and remember the outside world. We need to stop feeding the monsters that rob us of our peace and steal time away from the things that matter to us most,” he continued. Hearing Ferrara explains the meaning behind his song titles further revealed that he uses every part of his art, including those names as a way to express himself or share something. Nothing is left to chance, so while track titles might seem catchy or just plays on words, there’s much more to them.

At this point, our discussion switched gears and we began talking about Ferrara’s musical style and some of the playing methods he incorporates into his songs. Calling Ferrara’s style eclectic hardly does it justice since he plays everything from classical to jazz to funk and fusion, prog and there’s even some folk mixed in. He seamlessly intertwines the genres, layering them together and he makes interspersing them within the same song seem completely natural. I was interested to learn his trick, the secret sauce if you will, to marrying these seemingly incongruent genres. “Well, when I first started playing and throughout the early part of my career, my focus was on building my chops and becoming technically proficient as a bass player. It’s that idea of continuous improvement and a dedication to excellence that we talked about before. After a while, I’d developed a fairly diverse and sizeable set of tools to choose from, but that only goes so far. Playing fast or mastering some complex time signature, while cool, wasn’t enough. In order for me to connect with my audience and express myself, the music has to be more than a series of tricky, technical sections sewn together,” Ferrara explained.

Rather than focusing on a particular genre or writing with the intention of playing songs as a solo artist or with Consider the Source, he allows his emotions to shape the music. Ferrara wants whatever he happens to be feeling or going through at the time, good or bad, to come through in his songs. “In that way, it really is a marriage, connecting the mechanical side of playing with my emotions, an integration of body and soul. Playing and writing that way allows the mood to guide the music and I’m less cognizant of moving between styles or genres and more so aware of how well songs capture what I was feeling and what I hoped to express with them,” Ferrara shared.

In addition to his musical styles, I wanted to delve further into the various playing methods Ferrara uses on some the new record’s tracks, so I asked if he might provide a few examples. He explained, “An approach that I’ve found really works for me is doing a lot with a little. Doing so helps me develop themes that logically flow. That’s not to say that throughout my life I haven’t worked hard to develop a wide vocabulary of techniques and styles, but in this body of work, I gravitate toward certain techniques, chord shapes and rhythmic patterns that I’ve become fixated on. I went through a process of ‘following the thread’ to see if they lead naturally. Here are some songs that highlight the themes that permeate the album.

- “Zeros and Ones” showcases the use of different polyrhythms

- If you learn a polyrhythm, and you come up with a chord progression that has a smooth voice leading, referring to a logical way of spelling your chords that flow together nicely into one another, you’ll pretty much have a badass sounding musical idea. In this tune, I use two different polyrhythms, 5 against 3 for the A section and 2 against 3 for the B section. I like keeping the 3 through both sections because it helps tie together the craziness of it all and gives it a consistent groove to latch onto. It’s really fun for me to see how chord voicings mixed with rhythmic shifts create notes that bounce off of one another in very cool ways in pieces such as this.

- “Perhaps Everything, Perhaps Nothing” starts with a technique I call ‘drone tapping’

- New bassists and guitarists often lament the fact that they have several different versions of the same note in the same octave on the neck. This technique celebrates that annoyance. The idea is to pick two notes, find the same exact notes on another set of strings and play them with whatever rhythm you want. The effect it gives a listener is one of a rhythmic drone where the notes repeat quickly but with relatively minimal effort.

- “Riches to the Conjurer” has a Latin feel with a plucking, percussive bridge.

- I follow a rhythm that goes 12312312 with the ‘1’ being the note accented. I utilize shapes that span 4 voices per chord and I outline and change those voices often to keep it interesting. In the middle section of the song I use a right hand percussive method up by the pickups while the left hand taps chords and melodies. This creates a musical idea with a built-in backbeat that hints at a drum part.

- “The Gnome and the Skeleton” uses tapped left hand notes mixed with quick, right hand strums to generate a natural tremolo effect

- This technique is another example of ‘following the thread. I use the same rhythm used in sections of “Perhaps Everything, Perhaps Nothing,” which is a fast 4433 rhythmic articulation that’s actually a 7 pattern. The main difference in the technique in “The Gnome and the Skeleton” is that I’m only tapping the accented notes, the 1s, with my left hand while my right thumb, index, and sometimes middle fingers are all hitting the notes in the remainder of each subdivision.

- L RRR + LRRR + LRR + LRR

- Ls are all notes tapped on the fret board with the left hand and the Rs are added afterward with thumb down stroke, index upstroke, middle upstroke for the ‘4s’ and thumb down stroke, index upstroke for the ‘3s.’”

Listening to John Ferrara’s commentary during his live shows or just glancing through the names of his songs makes it readily apparent how important family is to him. “Song for Ramida” is dedicated to Ferrara’s goddaughter and “Say Charles” to his grandfather. Given that his father is a guitarist, I was curious to learn what role his father’s playing had on his decision to pick up the instrument and if he has any plans to collaborate or record with his dad. “You’re right! Family is very important to me and they’ve always been supportive of my playing and my pursuit of music as a profession. To this day, though age is taking its toll, my grandfather watches all of my YouTube videos and listens to all of my records. The arts were always a prominent fixture in our home, my mom directing community theater and my dad being a guitarist. I didn’t have much interest in playing when I was young, particularly since my older brother picked up the guitar first and was playing Hendrix solos in what seemed like no time at all. He was what everyone thinks of as the quintessential older brother, great looking and wow could he play that guitar! All kidding aside though, he and I have always had a great relationship and are still best friends to this day,” Ferrara shared.

He went on to say, “It wasn’t until I was about 12 or so that my dad finally got me to try playing. He taught me Hendrix’s “Hey Joe” and though I wouldn’t say I mastered it right out of the gate, I could hear myself playing the song, one of my favorite songs, pretty quickly after getting started. It was awesome and from that moment on, I was hooked.” Since his brother was a guitarist and at the behest of his father, Ferrara decided to take up the bass and, before long, his dad began creating opportunities for him to play on stage with touring bands. “It was an incredible experience and I learned a lot. Those guys were so much better than me. Quite frankly, I had no business being on stage with them at all, but the experience inspired me to practice and work even harder to develop my craft and eventually, make music my career,” Ferrara mused. “Getting back to your original question. Yes! I definitely plan to collaborate with my dad and we’re actually doing a show together as part of my mini-tour for the release of the second record, “ he continued.

Since our conversation had taken a turn toward his live shows, it offered a perfect segue for me to mention a performance that really stands out in my mind, his concert with Seth Moutal Live at The Museum of Modern Renaissance. Watching that show, one can’t help but notice that absolute joy Ferrara exhibits while playing, his facial expressions, his body language. I couldn’t help but wonder what made that show special enough to elicit such strong emotions. The way Ferrara explains it, it was everything, the museum, the music, working with Moutal, the audience and more. “The Museum of Modern Renaissance was amazing! It’s this old building that went through several transitions before two Russian artists bought it and turned it into what it is today. Every room is painted, decorated and used to display some type of art. On top of that, working with Seth is always terrific! He and I collaborate well and that night, all of our hard work and practice really paid off. We were in a groove, bouncing rhythms back and forth and improvising. That joy you saw on my face was real. Playing that show was a blast and, while this might sound kind of dorky, a big part of my excitement had to do with the fact that my now-girlfriend, Emily, was in the audience that night. I was stoked for her to be there and hear me play,” Ferrara chuckled. He went on to say, “Since we’re discussing that show, I really want to take the opportunity to thank Alice Feldman for helping Seth and me put it together and make that night happen!”

Something Ferrara mentioned in our initial discussion that he alluded to again here is that he finds playing music to be very therapeutic in addition to offering a creative outlet. He talks about how writing and recording this record helped him adapt to the changes surrounding the pandemic. Comparing Ferrara’s prior material with A Lesson in Impermanence, I wondered how him finding an escape in his music affected his work and what songs ultimately ended up on the record. Ferrara explained, ”As I mentioned, I don’t put any parameters around playing or writing. There’s no goal in mind for how a song will sound. It just happens and during the process, song elements find a way to intermingle all on their own, even if they might otherwise seem incompatible. It all stems from the idea of music being therapeutic if that’s how I defined it during our last conversation. If I had an awesome day, it comes through in the songs. They sound upbeat, fast, playful and fun. But if something has me down, it also comes through. Darker tones, brooding even. Or not. That rough day might lead me into some aggressive, percussive-style playing, kind of like going for a run and sweating off your frustrations. I’m just grateful to have music since it not only provides me with a healthy way to deal with whatever I’m feeling; I also have something to show for the catharsis afterward in the form of my songs.”

From my initial encounter with Ferrara and his music in March, 2017 to listening to his most recent release it’s been clear that he pours himself into his music withholding nothing, but trying to explain his sound to someone who’s never heard it is somewhat challenging. It’s not typical, rhythm section bass playing. At times, his two-handed tapping technique sounds more like classical guitar than bass, standing completely on its own with no need for accompaniment. One must see Ferrara’s slap technique to truly appreciate it, his hands moving so fast they become blurry to the onlooker’s eye. His sound and playing style are so unique, in fact, that as Ferrara explains, he’s gotten push back from other bass players. “More often than not, I get positive feedback via social media and even when I don’t, I know better than to feed the trolls. Better to just ignore them with the hopes that they’ll lose interest. There was one instance though, when a player who’d performed with some pretty big names made scathing comments on one of my socials regarding my style of playing, my two-handed tapping style, in fact. He went on about how it wasn’t bass playing, but sounded like solo piano or something. Against my better judgment, I engaged him in conversation and, after several hours of chatting, he and I actually saw eye-to-eye and became friends. No! My style isn’t necessarily traditional bass playing, but I don’t want to limit or restrain my creativity. Just because I play a bass shouldn’t confine me to any one style, method or genre,” Ferrara offered.

Ferrara’s story about his interaction on social media reminded me of something he mentioned during one of his live stream shows. Prior to performing Philip Glass’ “Glassworks” Ferrara talked a bit about how playing pieces such as “Glassworks” likened him more to a solo pianist than a bass player. He also mentioned how challenging it was for him to learn and perform that particular piece. With that in mind and given our prior discussion regarding his dedication to excellence and continuous improvement, I was interested to find out what challenges or hurdles he planned to tackle next. His response was something I definitely didn’t expect. “I’ll always work on my chops and techniques, but getting more technically proficient or mastering some new skill isn’t my top priority. The challenge now is finding new and different ways to use and incorporate all of the various techniques and methods I’ve learned into my music. It’s only natural to use things I know have worked in the past. Therein lies the challenge, not grabbing those trusty tried and trues, but forcing myself out of my comfort zone and finding success using different tools and ideas,” he explained.

As Ferrara and I closed our discussion, he emphasized two things that have been pivotal to his writing and teaching processes, tapping and the modes. “Aside from composing on a piano, I can’t think of anything that offers the compositional autonomy of tapping, be it on a bass or guitar. Tapping teaches players how chords and harmonies work and how to write. We actually play all the voices, experimenting with them and manipulating certain ones over others. Over time, tapping helps bass players develop a vocabulary of what we like to hear and gives us an opportunity to think more harmonically and melodically than when we normally just write or learn a bass line. With that in mind, I always encourage my students to learn tapping regardless of what style of playing they intend to pursue,” Ferrara told me.

He went on to say, “All we can do is try to tailor our study to those things we think will be most relevant to us, but that can be hard to know and sometimes we need to take our medicine and learn things we don’t care to. One thing I teach all of my students no matter what genre, technique or style they’re interested in learning are the modes. There are seven modes derived from the major scale alone and skipping notes in the scale creates arpeggios. There are probably a billion bass lines derived just from playing arpeggios. Understanding them and how they come together to create chords makes it possible for new players to start writing and gives them a vast toolbox to carry around with them. That’s just the major scale, kind of the mother scale here in the West, but there are countless more to learn. Once students learn the modes and the chords that go with them, they learn to look for low-hanging fruit, how to easily access notes in those shapes and play around with them. While the concept of low-hanging fruit might otherwise carry a negative or lazy connotation, what I’m referring to is the process of finding the notes easiest to grasp and maximize the advantage of those positions. After players reap the maximum benefit of those positions, I can start teaching them how to pursue other shapes or techniques.”

I love Mexican food; so using the modes reminds me of a joke that goes, ‘When you eat at a Mexican restaurant you always get a different version of the same ingredients. A burrito is just a big taco and a fajita is a burrito that you didn’t make yet.’ Regardless, the ingredients work well together and the result is always good. Using the modes is exactly the same. No matter how you combine the ingredients or in what order, they always work well together and the result sounds good,” Ferrara chuckled.

I learned a great deal during my lengthy conversations with John Ferrara, but what I took away most coincided perfectly with the title of his latest release, A Lesson in Impermanence. Ferrara is many things: bassist, composer, innovator, teacher, follower of Eastern philosophy and emotive expressionist. His bass is simply the implement of his art, but Ferrara’s quest for continuous improvement and exploring new ways of creating makes it impossible to pigeonhole him to one style, genre or technique. His passion for innovative creativity makes him and his art ever-evolving and, as such, he will never settle or stagnate. You never know what to expect from John Ferrara because as an artist he constantly pushes boundaries and fearlessly delves into uncharted territory, all of which make Ferrara himself A Lesson in Impermanence!

John Ferrara Featured Videos:

Visit online at johnferraramusic.com

Features

Alberto Rigoni On Unexpected Lullabies

Readers have been fans of the composer, bass player, and Bass Musician contributor Alberto Rigoni for some time now.

In this interview, we had the opportunity to hear directly from Alberto about his love of music and a project near and dear to his heart, “Unexpected Lullabies”…

Could you tell our readers what makes your band different from other artists?

In 2005, I felt the urge to write original music. My first track was “Trying to Forget,” an instrumental piece with multiple bass layers (rhythm, solo, and arrangement), similar to the Twin Peaks soundtrack. When I played it for a few people, they really liked it, and I decided to continue composing based on my instinct and ear without adhering to any specific genre. In 2007, I released “Something Different” with Lion Music. The title says it all! Since then, I’ve released many solo albums, each different from the others, ranging from ambient to prog, fusion, jazz, and new age. I am very eclectic!

How did you get involved in this crazy world of music?

As a child, I listened to the music my parents enjoyed: my dad loved classical music, while my mom was into Pink Floyd, Genesis, Duran Duran, etc. These influences left a significant mark on my life. However, the turning point came at 15 when a drummer friend played me “A Change of Seasons” by Dream Theater, which was a shock! From that moment, I decided to play bass and cover Dream Theater songs, which I did for many years with my cover band, Ascra, until it disbanded in 2004. After that, I joined TwinSpirits (prog rock) led by multi-instrumentalist Daniele Liverani. Since then, I haven’t played any more covers!

Who are your musical inspirations, and what inspired the album and the songs?

My roots are in progressive rock metal, with influences from bands like Dream Theater, Symphony X, and many others. However, I listen to all genres and try to keep an open mind, which helps me compose original music. On bass, I was significantly inspired by Michael Manring and Randy Coven (bassist of Ark, Steve Vai, etc.). But I don’t have a real idol; I just follow my own path without compromise.

What are your interests outside of music?

Living in Italy, I love good food and wine! Beyond that, I have a deep interest in art in general and history, not just of my country. I enjoy spending time with friends, skiing, biking, and walking in nature. This is how I spend my free time. The rest of my time is devoted to music and my family!

Tell us about the new album.

It is definitely an out-of-the-box album. When I found out last year that I was going to have a baby girl, I decided to compose a sort of lullaby album, but I didn’t want to cover already famous lullabies. So, I started composing new tunes with the goal of creating an album that was half-sweet and half-hard rock. I did include some covers like “Strangers in the Night” by Frank Sinatra, sung by Goran Edman, former lead singer of Malmsteen. It’s not exactly a lullaby, but I felt the lyrics fit the album, as does the instrumental version of “Fly Me to The Moon.” There are also tracks with just bass and piano (Nenia) or two basses (Vicky). It was definitely an interesting creative process!

What is the difference between the new album and your previous releases, and will there be any new material from your other outfit called BAD AS?

BAD AS is essentially a metal band with several influences including prog. My solo genre is quite different, although there are some metal songs on a few albums. It’s always difficult for me to categorize my music… let’s say it’s a mix of prog, ambient, fusion, and new age.

Where was the album recorded, who produced it, and how long did the process take?

I produced my last album entirely by myself, including mixing and mastering. Unlike other albums I’ve produced within a few months, this one took much longer, perhaps because I was very busy or maybe because I wanted it to be perfect for my daughter, who is now three months old. In any case, I am satisfied. Once again, I did something different from my previous albums.

What is the highlight of the album for you and why?

My favorite song is the first track titled “Vittoria,” named after my daughter. It’s the intro to the record and isn’t very long, but the melody stuck in my head. Another standout track is the instrumental version of “Fly Me to The Moon” by Frank Sinatra, where I used fretless bass. The first part is sweet, the second part definitely rocks!

How are the live shows going, and what are you and the band hoping to achieve?

With BAD AS, this year we shared the stage with David Ellefson’s (former Megadeth bassist) band and talented young singer Dino Jelusik (White Snake). We plan to continue performing all over Europe!

What’s in store for the future?

I am working on an instrumental project called Nemesis Call, a progressive shred prog metal album with various influences. It will feature guest appearances from famous musicians like drummers Mike Terrana and Thomas Lang, as well as young talents like Japanese guitarist Keiji from Zero (19), 14-year-old Indian drummer Sajan Young, and guitarists Alexandra Zerner and Alexandra Lioness, Hellena Pandora. It’s scheduled for release at the end of the year or early 2025. As an independent artist, I have launched a fundraising campaign with exclusive pledges at www.albertorigoni.net/nemesiscall. And no, I am not begging; the album will be released anyway!

What formats is the release available in?

Unexpected Lullabies is available both as a Digipack CD and on streaming platforms.

What is the official album release date?

June 4th, 2024.

Thanks for this interview Bass Musician Magazine and for the continued support to my career!

Visit Online:

www.albertorigoni.net

www.youtube.com/albertorigoni

albertorigoni.bandcamp.com

www.instagram.com/albertorigonibassplayer

www.facebook.com/albertorigonimusic

www.tiktok.com/@albertorigonibassist

CD Track Listing:

1. Vittoria

2. Fly Me to the Moon

3. Azzurra

4. Dancing with Tears in My Eyes (feat. John Jeff Touch)

5. Out of Fear

6. Veni Laeatitia (feat. Alexandra Zerner)

7. Nenia

8. Slap Lullaby (feat. Karl Clews)

9. Saga

10. Vicky (feat. Michael Manring)

11. Ocean Travelers (feat. Vitalij Kuprij)

12. Strangers in the Night (feat. Göran Edman)

13. Peaceful

14. Un uomo che voga (feat. Eleonora Damiano)

Band Line-Up:

- Tommaso Ermolli arrangements on “Vittoria”

- Sefi Carmel on “Fly Me to the Moon” (Cover) (except for the keyboard solo by Alessandro Bertoni)

- Piano and keyboards by Alessandro Bertoni on “Azzurra”

- Leonardo Caverzan, guitars, and John Jeff Touch, vocals on “Dancing with Tears in my Eyes” (Cover)

- T. Ermolli keys on “Out of Fear”

- Alexandra Zerner everything on “Veni Laetitia”

- Daniele Bof piano on “Nenia”

- Karl Clews, piccolo bass on “Slap Lullaby”

- Jonas Erixon vocals and guitars on “Saga”

- Michael Manring bass on “Vicky”

- Vitalij Kuprij, keyboards and piano, and Josh Sapna, guitars, on “Ocean Traveler”

- Göran Edman, vocals, Emiliano Tessitore, guitars, Emiliano Bonini, drums, on “Strangers in the Night” (Cover) everything by Alberto Rigoni and vocals by Federica “Faith”

- Sciamanna on “Peaceful”

- T. Ermolli, guitars, and Eleonora Damiano, vocals, on “Un uomo che voga All drums programmed by Alberto Rigoni

Bass Books

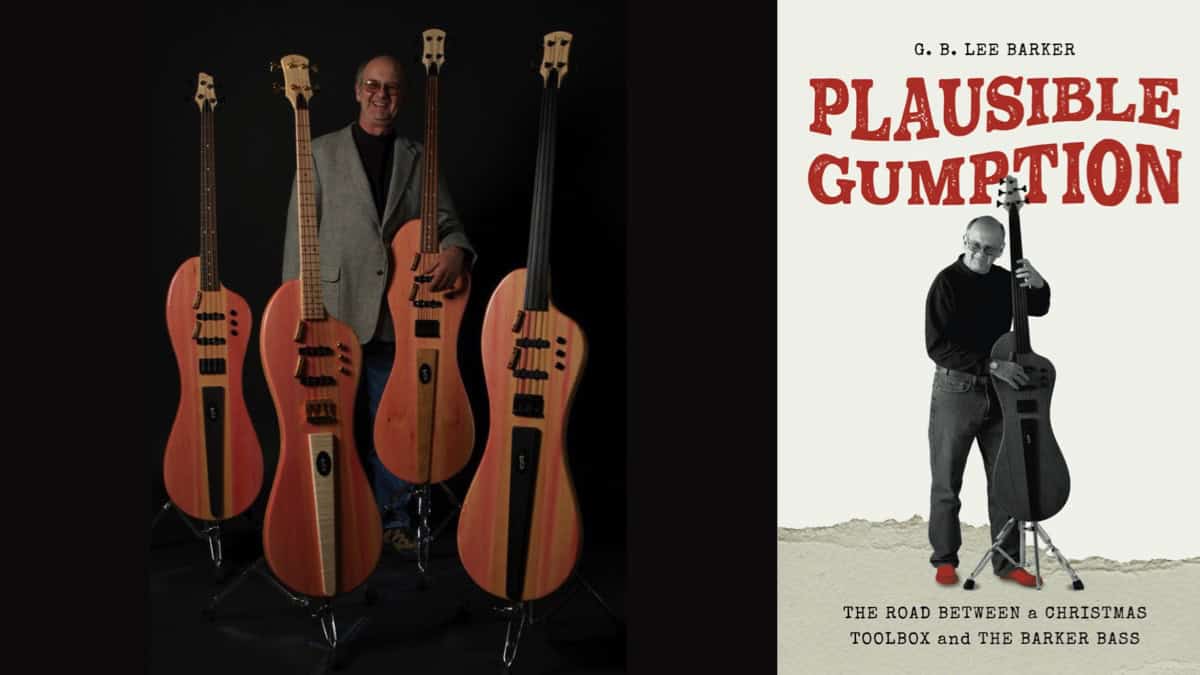

Interview With Barker Bass’s Inventor and Writer Lee Barker

If you are an electric bass player, this is an exciting time to be alive as this relatively new instrument evolves around us. Some creative individuals have taken an active role in this evolution and made giant leaps in their own direction. Lee Barker is one of these inventive people having created the Barker Bass.

Fortunately, Lee is also an excellent writer (among so many talents) and has recently released his book “Plausible Gumption, The Road Between a Christmas Toolbox and The Barker Bass”. This book is a very fun read for everyone and shares a ton of details about Lee’s life in general, his experiences as a musician, a radio host, and a luthier. Now I am fortunate to have the great opportunity to gain even more insights into this renaissance man with this video interview.

Plausible Gumption, The Road Between a Christmas Toolbox and The Barker Bass is available online at Amazon.com

Features

Bergantino Welcomes Michael Byrnes to Their Family of Artists

Interview and photo courtesy of Holly Bergantino of Bergantino Audio Systems

With an expansive live show and touring, Mt. Joy bassist Michael Byrnes shares his experiences with the joyful, high-energy band!

Michael Byrnes has kept quite a busy touring schedule for the past few years with his band, Mt. Joy. With a philosophy of trial and error, he’s developed quite the routines for touring, learning musical instruments, and finding the right sound. While on the road, we were fortunate to have him share his thoughts on his music, history, and path as a musician/composer.

Let’s start from the very beginning, like all good stories. What first drew

you to music as well as the bass?

My parents required my sister and I to play an instrument. I started on piano and really didn’t like it so when I wanted to quit my parents made me switch to another instrument and I chose drums. Then as I got older and started forming bands there were never any bass players. When I turned 17 I bought a bass and started getting lessons. I think with drums I loved music and I loved the idea of playing music but when I started playing bass I really got lost in it. I was completely hooked.

Can you tell us where you learned about music, singing, and composing?

A bit from teachers and school but honestly I learned the most from just going out and trying it. I still feel like most of the time I don’t know what I am doing but I do know that if I try things I will learn.

What other instruments do you play?

A bit of drums but that’s it. For composing I play a lot of things but I fake it till I make and what I can’t fake I will ask a friend!

I know you are also a composer for film and video. Can you share more

about this with us?

Pretty new to it at the moment. It is weirdly similar to the role of a bass player in the band. You are using music to emphasize and lift up the storyline. Which I feel I do with the bass in a band setting. Kind of putting my efforts into lifting the song and the other musicians on it.

Everybody loves talking about gear. How do you achieve your “fat” sound?

I just tinker till it’s fat lol. Right now solid-state amps have been helping me get there a little quicker than tube amps. That’s why I have been using the Bergantino Forté HP2 – Otherwise I have to say the cliche because it is true…. It’s in the hands.

Describe your playing style(s), tone, strengths and/or areas that you’d like

to explore on the bass.

I like to think of myself as a pretty catchy bass player. I need to ask my bandmates to confirm! But I think when improvising and writing bass parts I always am trying to sneak little earworms into the music. I want to explore 5-string more!

Who are your influences?

I can’t not mention James Jamerson. Where would any of us be if it wasn’t for him? A lesser-known bassist who had a huge effect on me is Ben Kenney. He is the second bassist in the band Incubus and his playing on the Crow Left the Murder album completely opened me up to the type of bass playing I aspire towards. When I first started playing I was really just listening to a lot of virtuosic bassists. I was loving that but I couldn’t see myself realistically playing like that. It wasn’t from a place of self-doubt I just deep down knew that wasn’t me. Ben has no problem shredding but I was struck by how much he would influence the song through smaller movements and reharmonizing underneath the band. His playing isn’t really in your face but from within the music, he could move mountains. That’s how I want to play.

What was the first bass you had? Do you still have it?

A MIM Fender Jazz and I do still have it. It’s in my studio as we speak. I rarely use it these days but I would never get rid of it.

(Every bass player’s favorite part of an interview and a read!) Tell us about

your favorite bass or basses. 🙂

I guess I would need to say that MIM Jazz bass even though I don’t play it much. I feel connected to that one. Otherwise, I have been playing lots of great amazing basses through the years. I have a Serek that I always have with me on the road (shout out Jake). Also have a 70’s Mustang that 8 times out of 10 times is what I use on recordings. Otherwise, I am always switching it up. I find that after a while the road I just cycle basses in and out. Even if I cycle out a P bass for another P bass.

What led you to Bergantino Audio Systems?

My friend and former roommate Edison is a monster bassist and he would gig with a cab of yours all the time years ago. Then when I was shopping for a solid state amp the Bergantino Forté HP2 kept popping up. Then I saw Justin Meldal Johnsen using it on tour with St. Vincent and I thought alright I’ll give it a try!

Can you share a little bit with us about your experience with the Bergantino

forte HP amplifier? I know you had this out on tour in 2023 and I am pretty

certain the forte HP has been to more countries than I have.

It has been great! I had been touring with a 70’s SVT which was great but from room to room, it was a little inconsistent. I really was picky with the type of power that we had on stage. After a while, I thought maybe it is time to just retire this to the studio. So I got that Forte because I had heard that it isn’t too far of a leap from a tube amp tone-wise. Plus I knew our crew would be much happier loading a small solid state amp over against the 60 lbs of SVT. It has sounded great and has really remained pretty much the same from night to night. Sometimes I catch myself hitting the bright switch depending on the room and occasionally I will use the drive on it.

You have recently added the new Berg NXT410-C speaker cabinet to your

arsenal. Thoughts so far?

It has sounded great in the studio. I haven’t gotten a chance to take it on the road with us but I am excited to put it through the paces!

You have been touring like a madman all over the world for the past few

years. Any touring advice for other musicians/bass players? And can I go to Dublin, Ireland with you all??

Exercise! That’s probably the number one thing I can say. Exercise is what keeps me sane on the road and helps me regulate the ups and downs of it. Please come to Dublin! I can put you on the guest list!

It’s a cool story on how the Mt. Joy band has grown so quickly! Tell us

more about Mt. Joy, how it started, where the name comes from, who the

members are and a little bit about this great group?

Our singer and guitarist knew each other in high school and have made music together off and on since. Once they both found themselves living in LA they decided to record a couple songs and put out a Craigslist ad looking for a bassist. At the time I had just moved to LA and was looking for anyone to play with. We linked up and we recorded what would become the first Mt. Joy songs in my house with my friend Caleb producing. Caleb has since produced our third album and is working on our fourth with us now. Once those songs came out we needed to form a full band to be able to do live shows. I knew our drummer from gigging around LA and a mutual friend of all of us recommended Jackie. From then on we’ve been on the road and in the studio. Even through Covid.

Describe the music style of Mt. Joy for me.

Folk Rock with Jam influences

What are your favorite songs to perform?

Always changing but right now it is ‘Let Loose’

What else do you love to do besides bass?

Exercise!

I always throw in a question about food. What is your favorite food?

I love a good chocolate croissant.

Follow Michael Byrnes:

Instagram: @mikeyblaster

Follow Mt. Joy Band:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/mtjoyband

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/mtjoyband

Bass Videos

Artist Update With Mark Egan, Cross Currents

I am sure many of you are very familiar with Mark Egan as we have been following him and his music for many years now. The last time we chatted was in 2020.

Mark teamed up with drummer Shawn Pelton and guitarist Shane Theriot to produce a new album, “Cross Currents” released on March 8th, 2024. I have been listening to this album in its entirety and it is simply superb (See my review).

Now, I am excited to hear about this project from Mark himself and share this conversation with our bass community in Bass Musician Magazine.

Photo courtesy of Mark Egan

Visit Online:

markegan.com

markegan.bandcamp.com

Apple Music

Amazon Music

Bass Videos

Interview With By the Thousands Bassist Adam Sullivan

Bassist Adam Sullivan…

Hailing from Minnesota since 2012, By the Thousands has produced some serious Technical Metal/Deathcore music. Following their recent EP “The Decent”s release, I have the great opportunity to chat with bassist Adam Sullivan.

Join me as we hear about Adam’s musical Journey, his Influences, how he gets his sound, and the band’s plans for the future

Photo, Laura Baker

Featured Videos:

Follow On Social

IG &FB @bythethousands

YTB @BytheThousands