Latest

Music: The Language and The Art by PW Farrell

The course was a Post Graduate Diploma in Performance; it’s basically a baby Masters Degree and it gave me the opportunity to research and present two papers: Why Music Exists: An Exploration of the Lexicon of Sound and Bass Guitar: The Influence of Design, Industry, Genre and Technique on Performance Practice. In writing these papers, I stumbled on some facts, both concerning the ‘nuts and bolts’ of music theory/sound and concerning music as an art form. The points raised in these papers are, to me, extremely relevant to the modern musician and yet very rarely taught in music education.

Some points raised address musical understanding. For example, how many musicians were ever taught why the octave exists at all in music theory? Is it an abstract concept or is it based on measurable, explainable phenomena? Why does a b9 chord sound different (darker/more complicated) to a major 6 chord? Some of the points address issues of musical performance. For example, what are the ramifications of electronically amplified sound versus acoustically amplified sound (or why do bass players get no TV time)? And what exactly is music? I mean where did it come from in the first place, and does this explain why we continue studying and creating it despite comparatively menial economic returns and social marginalisation?

What I intend to present here over the coming months are articles based on my findings – sans academic hyperbole. Topics covered include: The Birth of Music, The Syntax of Music, The Influence of Design and Technology on How We Play, Art vs Super Mart and anything else that seems relevant. Beyond that I’d like to share a few things I’ve learnt over the last 20 years of playing and teaching bass.

So what’s first? Well I think as good a place to start as any, is the very beginning.

The Harmonic Series – Syntax of the Musical Language

I’ll tell you what is absolutely nuts. Bonkers. CRAY – CRAY! Because you are a product of the universe, you can not observe it objectively as a third party – your tools of perception are a product of the elements you are observing. What the hell do I mean? Ok, take waveforms. If you emit a sound wave, the rippling sympathetic sound waves which are generated occur at a consistent set of incrementally smaller ratios known as the Harmonic Series. You may not always be able to pitch these sympathetic sound waves themselves, however you will always hear the richness and colour these overtones bring to the fundamental tone (‘Man this bass sounds fat!’ etc).

This is the nutso bit: your ears perceive pitch based on the same values as the Harmonic Series. This might sound obvious (pun unintended – yet charming) but think about it – if you perceived pitch linearly, this whole universe would sound, well, like poop. What is the Harmonic Series exactly? Let’s use an example that is not music – just noise…

If I strum a banjo string, not only will Cletus mute the Nascar coverage (Bazinga!) but the string will almost instantly start oscillating at smaller and smaller increments. The first oscillation is the full length of the string, the next oscillation is half the length of the string, then a third, quarter, fifth etc. These sympathetic oscillations might be almost impossible to hear, but they are there and continue to generate until the energy in the string is exhausted.

You can see similar phenomena with other waveforms, for example, if you throw a TV playing Nascar footage in a pond, the wavelets will radiate outwards and decrease in size at predictable ratios until the energy is expired. It all depends on the size of the TV.

In reality, it’s pretty self explanatory (to a point); we evolved in a logarithmic universe and thus our faculties evolved in a similar fashion. But it is worth taking a closer look at the Harmonic Series because understanding it is the key to understanding why music theory makes sense.

Let’s take a musical example….

If we pluck a 1960s P Bass A string at the third fret, we generate a concert C note. This is our ‘fundamental’. Almost instantly, a sympathetic wave half as long (= twice as fast) is generated. Because our ears analyse data logarithmically, they understand pitch in comparative ratios. In other words, if the first C note is 65.4hz and the first sympathetic sound wave is 130.8hz, our ears instantly recognise that the second wave is exactly twice the frequency of the first, and such an easy-to-process ratio relationship that the second note is directly related to the first – even if it is higher in the audio spectrum. That is what an octave is; the ear saying ‘hey I find those two pitches really easy to relate and compare…. what a positively non-confronting ratio!’

Maybe a good visual equivalent would be looking at a chair from 50m and then placing another chair 100m away within eye sight of the first. You know you are looking at two different chairs and you know the second is far too small for Cletus to sit on, but they are both chairs nonetheless and you’re satisfied. Satisfied? Good.

So what happens next? We have our first two sound waves of the harmonic series: C1* the fundamental and C2* the octave above that. Well let’s think about it. The next sympathetic sound wave is 3 times as fast as the first. Think about music theory and this riddle can be solved rationally with no science necessary. Next to an octave what is the simplest, most common interval? Let’s go back to Cletus… When he picks up his cousin’s rum-stained acoustic and plays Sweet Home Alabama, what chord voicing does he use? Keep in mind Cletus doesn’t really know what he’s doing; he’s just following his intuition and punching out thick sounding bar chords. Well, I think he’s probably going to reach for ‘power chords’ voiced 1 – 5 – 1 or even just 1 and 5. This is because the 5th is almost as simple a ratio as the octave and yet harmonious enough to pass the mustard as a chord tone.

So we have our first three pitches of the Harmonic Series:

- the root or fundamental – C1

- the next wave vibrating 2:1 times as fast as the first = C2 (octave above C1)

- the third vibrating 3:2 as fast as the second = G (fifth above C2)

Because I’m using a musical example, it creates the illusion that the Harmonic Series is a man made musical theory concept. But remember THIS IS PHYSICS! Sound just works this way! As the ancients tried to understand sound, they stumbled upon the same phenomena I am now describing and they did so purely intuitively; but that doesn’t diminish the science of it – it only serves to prove it.

For example the oldest playable harmonic instruments ever found are from Henan Province, China, and date back as far as 9,000 B.C. The collection of flutes feature five to eight holes:

“Tonal analysis of the flutes revealed that the seven holes correspond to a tone scale remarkably similar to the Western eight-note scale that begins “do, re, mi.” This carefully selected tone scale suggested to the researchers that the Neolithic musician of the seventh millennium BC could play not just single notes, but perhaps even music (harmonies).”

~ Juzhong Zhang, Wang, Kong and Harbottle

What is perhaps more provocative, is that there is evidence of the instruments being altered after their initial construction for tuning purposes. These early musicians had more pride in their intonation than some pub singers!

If we were to continue working through the Harmonic Series and reverting the pitches back to music theory, we would come up with a scale that approximates the major scale very closely (actually the 7th we arrive at is very flat, making the scale closer to a mixolydian scale). Eventually, the increments become smaller than our 12 tone tuning system can easily document. See the figure below (wiki): the numbers above each pitch indicate how out-of-tune with tempered concert pitch they are.

Here’s the thing. You can actually explain our perception of pitch without referencing the harmonic series; you could say we hear logarithmically, and therefore harmonic relationships are really ratio relationships – and that’s that. But this does little to explain why we evolved to hear this way in the first place and it doesn’t address the fact that musical harmony (in terms of music theory) is a phenomenon occurring naturally in nature. Even within a single note.

The fact is that within every tone, the macro goings-on which we can clearly witness (the sound of harmony) also exist – even if imperceptible to most people at most times – and I believe this goes a long way in explaining just why it is that our sense of hearing and perceiving pitch developed the way it did.

What the Harmonic Series represents to me is two things:

- an example of the subtle, constant pressures of the universe influencing the evolution of life within that universe: every sound wave has exerted the Harmonic Series since the dawn of time and therefore informed life as to how to perceive sound.

- the smallest possible nugget of musical syntax present in nature; that is the DNA of music

Now what does all this mean for you the musician? First of all, if you’re an electric bass player, you can have some serious fun with the Harmonic Series. You play the most apt instrument for exploring it. The register of the instrument, the mode of sound production (plucked strings) and the fact that it is amplified means it can produce clear, ringing harmonics better than just about any other instrument. Whenever you have a length of string (it’s only more common to play harmonics on open strings because most of us only have two hands), you can ascend the Harmonic Series (relative to the fundamental – the pitch of the open string) by dividing it into incrementally smaller fractions. So if you play an A string and then lightly touch it at the 12th fret (half way) and play that harmonic, you will hear the second pitch of the harmonic series based on A1 – A2. Again, if you lightly touch the A string at the 7th fret (a third) and play that harmonic, you will hear E2 (a 12th or Octave + a 5th above the open A string), and so on.

Also, understanding the logarithmic nature of pitch recognition explains why harmony is relative; why for example an F# over a D wants to pitch slightly flatter than an F# over a B. If you have a fretless bass try this out for yourself: if you are really listening (and you’ve tuned up, Cletus…) you will notice that to get a truly harmonious Jaco moment going on, your F# finger will need to ever so slightly change position over each bass note (D and F#). As we start playing in ensembles and richer harmonies we (well I do…) surrender to tempered harmonic standards and battle onwards.

So do you get it? What we do as musicians is deal with a language unlike any other. The written and spoken word are a series of arbitrary symbols organised by arbitrary systems, and thus 1000s of languages populate this green earth. Music on the other hand is codified by laws of physics – and is thus truly universal! Cool hey? Better than Nascar even! Despite the fact that I might enjoy the ratio-istic orgy of an altered chord, and Cletus might prefer the down home honesty of a power chord, we are both perceiving the data the same way; both understanding in an intuitive manner the syntax of the musical language.

*Throughout the article I refer to the tones of the Harmonic Series by their note name and octave (relative to the fundamental tone of that Harmonic Series). For example the Harmonic Series in C would be C1 – C2 – G2 – C4 – E4 etc.

PW Farrell is an Australian session musician and solo artist. His critically acclaimed debut album is available on iTunes.

Bass Videos

Gear News: Spector Launches Euro CST and Euro LX Basses

Spector, a leading authority in bass guitar design, unveils new additions to its product line: Euro CST, Euro LX and Euro LX Bolt On basses.

Euro CST:

The Euro CST introduces all-new tonewoods, electronics, and finish combinations never seen in the Euro Series, drawing inspiration from Spector’s Woodstock, NY-based Custom Shop. Each Euro CST instrument is meticulously crafted using premium materials, featuring a striking, highly figured Poplar Burl top, a resonant European Ash body, and a 3-piece North American Maple neck paired with an Ebony fingerboard adorned with laminated Abalone Crown inlays.

Euro CST basses are equipped with a lightweight aluminum bridge for precise and reliable intonation. Premium active EMG X Series pickups deliver the exceptional clarity, attack, and silent operation that defines the Spector sound. These basses also feature the all-new Spector Legacy preamp. Developed in collaboration with Darkglass Electronics, this preamp captures the classic “Spector growl,” heard on countless iconic recordings, with added versatility.

Euro CST basses are available in 4- and 5-string models in four distinct high gloss finishes: Natural, Natural Black Burst, Natural Red Burst, and Natural Violet Burst.

Euro LX and Euro LX Bolt-On:

The Euro LX offers all the features that have made the Spector name famous around the globe. Inspired by the iconic NS-2, Euro LX basses feature a fully carved and contoured body, high-grade tonewoods, and professional-grade electronics and hardware. For the first time ever, players can now choose between neck-thru and bolt-on construction in the Euro LX range.

Each Euro LX bass, regardless of construction, is crafted using premium materials, including a European Alder body, figured European Maple top, and a 3-piece North American Maple neck combined with a Rosewood fingerboard for strength, stability, and sustain. Euro LX basses are then outfitted with a lightweight, aluminum bridge for spot-on, reliable intonation. Premium active pickups from EMG provide the exceptional clarity, attack, and silent operation that Spector is known for. Like the Euro CST basses, these instruments also feature the all-new Spector Legacy preamp.

The newly revised Euro LX range is available in four distinct, hand-rubbed stains, including Transparent Black, Natural Sunburst, Haunted Moss, and Nightshade. Each of these colors features a durable and comfortable matte finish.

John Stippell, Director, Korg Bass Division, remarks, “I’m thrilled to announce the latest additions to the renowned Euro Range. The CST Series, our new premium offering, features new and unique wood combinations and unprecedented features. The beloved LX Series is now better than ever with the introduction of Bolt-On models, vibrant new color options, and the all-new Spector Legacy Preamp, delivering the classic Spector tone with unmatched precision.”

For more information, visit spectorbass.com.

Latest

Luthier Spotlight: Garry Beers, GGB Basses

Meet Garry Beers, Luthier and owner of GGB Basses…

Bass Musician Magazine: How did you get your start in music?

Garry Beers: I played acoustic guitar as a kid with my mates at school. We decided that one of us should play bass, so we had a contest where the one who knew the least guitar chords would buy a bass – so I lost the contest, bought my first bass, and became the only bass player in the neighborhood. Soon after, I met Andrew Farriss, who had heard that I had a bass, and a few days later, I was jamming with Andrew and Jon Farriss.

Are you still an active player?

Yes, I am still actively writing music and playing bass sessions. I also have an LA-based original band called Ashenmoon.

How did you get started as a Luthier? When did you build your first bass?

I did woodwork in High School and always enjoyed making all sorts of things out of wood.

After finishing high school, I took a course in electronics for a year or so and learned enough to understand basic circuits in guitars, amplifiers, and effects. The best way to learn is to deconstruct and study, so my dad’s garage was littered with old junked radios and any instrument parts I could find.

My first guitars were more like Frankenstein-type creations made out of parts I found here and there. I didn’t really try to build a bass from scratch until I perfected my Quad pickup design and got my patent.

How do you select the woods you choose to build with?

I only use woods that were used at Fender in the 50s, which are my favorite basses and guitars of all time. All my GGB basses are modeled in some way from my INXS bass- a 1958 Fender Precision bass I bought in 1985 in Chicago. I call her “Old Faithful,” and she has an Alder wood body with a maple neck. All of my GGB basses are select Alder wood bodies that I have had extra dried, so they match the resonance of “Old Faithful,” as she has had 66 years to lose all her moisture and become more resonant and alive-sounding. I use plain old Maple necks that I carefully select, and again, I dry the necks to make them sing a little more.

Tell us about your pickups.

I started working on my Quad coil design back in Australia in the ‘90s and then put it to bed, so to speak, until I found an old pickup winding machine at a swap meet here in LA. I taught myself enough about pickup winding to build my first prototype design and worked towards my patented Quad coil design by trial and error. Nordstrand Audio builds the pickups for me here in SOCAL.

What is the reaction of players who pick up your basses?

I build the basses to feel like an old friend. They look and feel vintage, and when you plug them in, you discover the array of vintage sounds available to you from just one pickup. Most of the players I have contact with are established professional players, and they all love the basses. Freddie Washington and Nick Seymour from Crowded House are a couple of players with GGB Basses in their hands.

What are a few things that you are proud of in your instruments and would consider unique?

I would say I am most proud of the patented Quad pickup design. I own the patent from 4 through to 10-string. So far, I have only built 4 and 5-string pickups, but the design is a winner. Split Humbucker / Reverse Split Humbucker / Full Humbucker / Single coil Neck / Single coil bridge. All these sounds come from one passive pickup. I am very proud that my perseverance and desire to have this pickup have made it a reality. Being able to have these sounds in one bass enables the player to have one bass in the studio and on the stage. The only place you can have the GGB Quad pickup is in one of my GGB Basses.

Which one of the basses that you build is your favorite one?

I offer three body shapes and about ten different color options – all based on the ‘50s and early ‘60s custom guitar and car paint styles. I have always been a lover of P basses, but my favorite bass I build is now my XS-1 model- which is a custom Jazz bass body style. It is pretty sexy and is a light, well-balanced, and great-feeling body shape. The other body styles are the XS-2, which is a custom Jazzmaster body and has been the most popular so far- and the XS-3, which is the standard P bass body style. I also offer an XS-58, which is a replica of my “Old Faithful” ‘58 P bass. They are currently available to order now and should be available soon.

Can you give us a word of advice to young Luthiers who are just starting out?

I don’t really consider myself a Luthier in the traditional sense. I just love to build things and tinker. I was always looking to improve things, whether it was a guitar, an amp, a pedal board, or a car. So my advice is to always be curious and learn the basics of what you want to build, and the rest should follow once you decide what you want to say as a designer/builder. People are lucky these days that you can learn pretty much anything from talented people on the internet, but nothing replaces working with and learning from real people in real situations. Seek out like-minded builders and start a discussion.

What advice would you give a young musician trying to find his perfect bass?

Have a good hard think about what you want to say as a player. What is your style, both musically and as a player? There are so many instruments available. Do the research, play the instruments that fit your criteria, and make a decision. But make sure you try a GGB Bass! With all the sound choices my basses offer, with a simple turn of a knob, you may find it easier to find “your” sound.

What is the biggest success for you and for your company?

Well, the company is brand new, and at this point, it is just me, so getting this far in the manufacturing process and now having these amazing basses in my hands is a great achievement, but now comes all the business stuff!!

What are your future plans?

It’s a work in progress. Right now, it’s all about getting the word out and getting the basses into the hands of interested players. I believe in the basses – and the Quad pickup, so hopefully, GGB Basses can become a go-to bass for demanding studio and live players who want sound choices in a gorgeous vintage-style instrument.

Visit online at www.ggbbasses.com

Gear Reviews

Gear Review: Joyo Monomyth – A Versatile Modern Bass Preamp

Disclaimer: This pedal was kindly provided by Joyo for the purpose of this review. However, this does not influence our opinions or the content of our reviews. We strive to provide honest, unbiased, and accurate assessments to ensure that our readers receive truthful and helpful information.

Introduction:

The Joyo Monomyth bass preamp pedal is designed to offer bassists a comprehensive range of tonal options, combining modern features with practical functionality. With independent channels for EQ and overdrive, as well as useful additions like a cab sim and DI output, the Monomyth aims to be a versatile tool for both live performances and studio sessions. This review will delve into the pedal’s specifications, controls, and overall performance to determine if it lives up to its promise of delivering quality and flexibility at an affordable price.

Specifications:

– Dimensions: 130 * 110 * 50 mm

– Weight: 442g

– Working Voltage: DC 9V

Controls:

The Joyo Monomyth is equipped with a comprehensive set of controls designed to provide maximum tonal flexibility:

– Voice: Adjusts the character of the overdrive, from distortion to fuzz.

– Blend: Balances the dry and effected signals, crucial for maintaining low-end presence.

– Level: Sets the overall output volume.

– Drive: Controls the amount of gain in the overdrive channel.

– Treble Boost: Enhances high and mid frequencies for clarity in complex passages.

– Gain Boost: Adds extra gain, particularly effective at low gain settings to enhance the low e.

– EQ Function Controls: Features a 6-band graphic EQ plus a master control for precise nal shaping.

– Ground Lift Switch: Helps eliminate ground loop noise.

– Cab Sim Switch: Activates a simulated 8×10″ cab sound.

– LED Light Control: Customizes the pedal’s ambient lighting.

Performance:

The Joyo Monomyth shines in its dual-channel design, offering both a transparent EQ channel and a versatile overdrive channel. The 6-band EQ allows for detailed tonal adjustments, preserving the natural character of your bass while providing ample flexibility. The voice control mimics the functionality of the Darkglass Alpha Omega, shifting from distortion to fuzz, with a sweet spot around the middle for balanced tones.

The blend control is essential for retaining the low end when using distortion, ensuring your bass remains powerful and clear. The treble and gain boosts, available on the overdrive channel, further enhance the pedal’s versatility, making it suitable for everything from subtle drive to full-blown fuzz.

Outputs are plentiful, with a DI and XLR out for direct recording or ampless setups, and a headphone out for convenient practice sessions. The cab sim switch adds a realistic 8×10″ cab sound, enhancing the Monomyth’s utility in live and studio environments.

Pros:

– Versatile Control Set: Offers a wide range of tones, from clean to fuzz.

– Blend Control: Maintains low-end presence.

– Robust Outputs: DI, XLR, and headphone outs make it adaptable for various setups.

– Affordable: Provides high-end functionality at a budget-friendly price.

– Sturdy Construction: Durable build quality ensures reliability.

Cons:

– Plastic Knobs: May feel less premium compared to metal controls.

– Boosts Limited to Overdrive Channel: Treble and gain boosts do not affect the EQ channel.

– Cab Sim only on the XLR out: how cool would it be to also have it on the headphone out?

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the Joyo Monomyth stands out as a versatile and powerful bass preamp pedal, offering a range of features that cater to both traditional and modern bassists. Its dual-channel design, comprehensive control set, and robust output options make it a valuable tool for achieving a wide spectrum of tones, from clean and warm to heavily distorted. For bassists seeking flexibility, reliability, and excellent value, the Joyo Monomyth is a top contender.

For more information, visit online at joyoaudio.com/product/267.html

Latest

July 15 Edition – This Week’s Top 10 Basses on Instagram

Check out our top 10 favorite basses on Instagram this week…

Click to follow Bass Musician on Instagram @bassmusicianmag

FEATURED @mikelullcustomguitars @maruszczyk_instruments @foderaguitars @marleaux_bassguitars @meridian_guitars @dmarkguitars @benevolent_basses @sandbergguitars @bassworkshopau @glguitars

Bass Videos

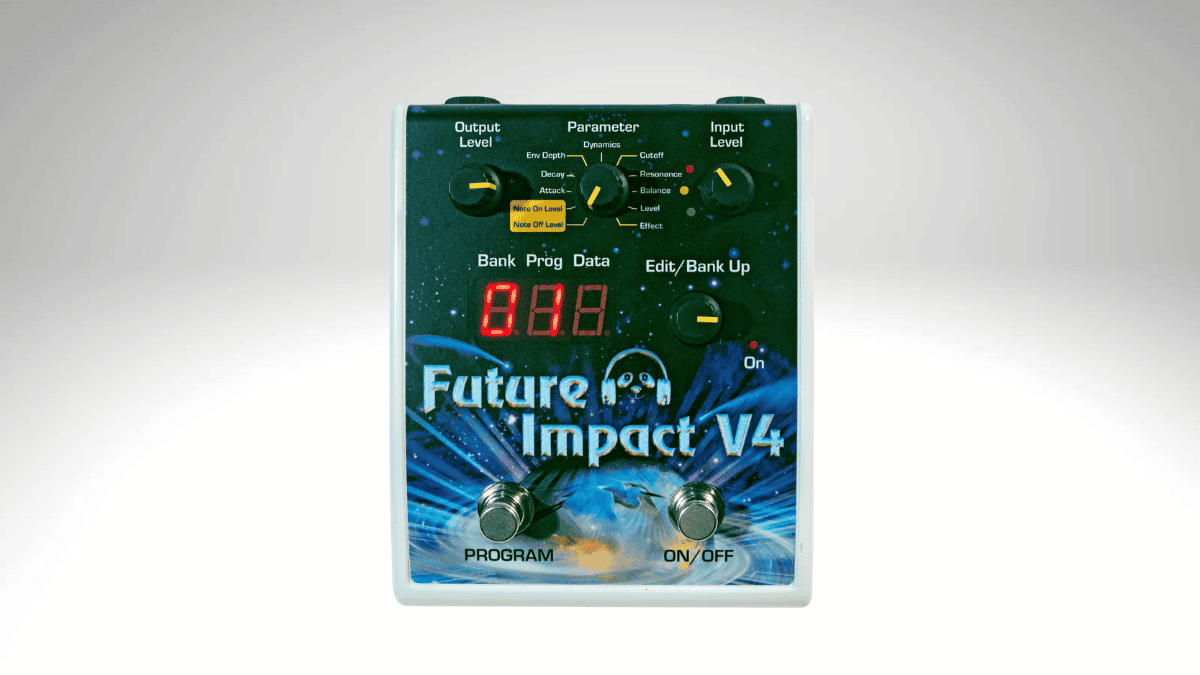

Gear News: Future Impact V4 Guitar & Bass Synth Now Available in the U.S.

Future Impact V4 Guitar & Bass Synth Now Available in the U.S….

The Future Impact V4 is an incredibly versatile pedal with an exceptionally wide range of sounds. In addition to producing synthesizer sounds such as basses, leads and pads, it can function as an octaver, chorus, flanger, phaser, distortion, envelope filter, traditional wah-wah, tremolo, reverb, etc., and even has a built-in tuner. It can also drive external synthesizer gear via the optional CV/Gate. As such, it can potentially replace an entire pedalboard of dedicated single-effect pedals.

The very powerful signal processor of the Future Impact V4 is able to replicate the various oscillator, filter, amplifier and envelope generator blocks found in classic synthesizers. In addition, it contains signal processing blocks more traditionally used for processing the sound of an instrument such as a harmonizer block and audio effects such as chorus, distortion and EQ. These architectures complement each other in a very flexible way.

Check out this short video with new sounds:

The Future Impact V4 has a completely new hardware platform with numerous enhancements, some of which are:

– 32-bit ultra-low-noise analog-to-digital and digital-to-analog converters

– New app-based software architecture

– Vastly advanced pitch tracking based on 30+ years of experience

– Hard Sync between oscillators to open new sonic worlds

– On-pedal edits that can be saved into program memories

– Total compatibility with all previous Deep Impact and Future Impact patches

Setting the standard for the bass guitar synth pedals since 2015, together with an enthusiastic community and long line of great artists, the Future Impact V4 is the guitar synth platform for the next decade.

For more information, visit online at pandamidi.com/bass-guitar-synth

Exclusive U.S. distribution by Tech 21 USA, Inc