Cover

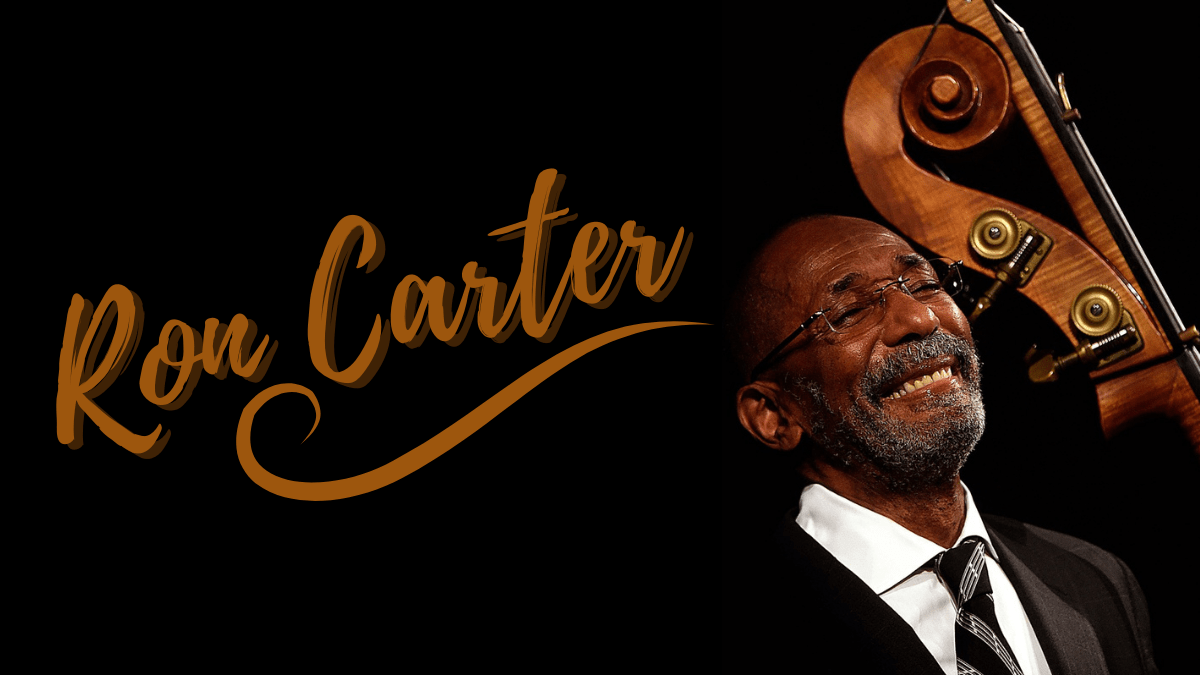

A Conversation With Mr. Ron Carter: July 2021 Issue

A Conversation with Mr. Ron Carter By David C. Gross and Tom Semioli…

An icon of the instrument, a jazz giant, and an insightful educator – Ron Carter discusses his latest book aptly entitled CHARTOGRAPHY (roncarterbooks.com) which transcribes five performances of “Autumn Leaves” as played by Miles Davis’ Second Quartet circa 1963-1967.

Says Ron: “A single, one-chorus transcription of a bass line you admire cannot help you learn to do it yourself. But if you understand all the elements and the context that went into creating it, you can up your game and learn to write bass lines like the ones that inspired you.”

Mr. Carter also reflects on; the current state of jazz, the performing arts and education; his practice philosophy, and how he was never intimidated by the emergence of the electric bass, among other topics. This interview aired on NOTES FROM AN ARTIST (formerly The Bass Guitar Channel Radio Show on cygnusradio.com every Monday night at 8 PM ET) in May 2021.

What can we say about one of the greatest bassists, educators, composers, bandleaders most recorded bassists? Well, if I don’t stop now, by the time I am reading all of his credits the show will be over so why don’t we get started?

The legend for this interview is as follows:

RC=Ron Carter / TS=Tom Semioli / DG=David C. Gross

TS: You’re in your familiar “Ron Carter Media Center.”

RC: My natural habitat!

TS: Ron, since the COVID intermission which you have termed, you have become somewhat of a media personality. My goodness. I’ve seen your interviews with Lenny White, Herbie Hancock, Pat Metheny. What inspired you to go online?

RC: Well, the three people who trust my judgment and whose judgement I’m forced to trust, their thought was that the more I stay in my natural habitat, and then continue hibernating, no one would know who I was of the people who were supposed to know who I was and they convinced me that they would trust my image and my responsibility and my history. And if I said ‘no,’ I would mean really ‘no’ and if I said ‘yes,’ that means I’m trusting them as far as we could go. And it’s been working out pretty well, I think.

TS: I enjoyed your interview with Herbie talking about how Zoom has now become part of our lives and it being a great tool to be able to talk to people that you wouldn’t ordinarily have the opportunity to connect with.

RC: I think more importantly for me, it allows me to teach students somewhere other than a block from my house. I have a student who is in Greece. So, he gets the lesson at 7:00 AM New York time because it’s like 6:00 PM there or something like that. He’s such a wonderful player. He needs some help and that’s my job. If it were not for Zoom, I would never have known he existed.

TS: What are some of the dynamics when you teach on Zoom? Obviously, it’s not the same as being there in person.

RC: It’s really difficult given everything that’s involved with the local Wi Fi, the internet system people are using at the time. ‘What kind of gear does he have to allow me to get the best sound from him through the system? Can I accept at some point that he’s going be frozen for twenty bars?’ I will hear nothing of what he’s doing and I’m trying to follow my score.

I mean, it’s fraught with difficulty and our job our, meaning the teaching collective as a final way to understand what that is and understand that there’s a different ballgame. Now, the other big issue is that I found is the bane of my existence is that the academic teachers give the students more work because they think that that now they’re at home and they have much more time to pile on the work.

Extra math, extra assignments, extra research extra term papers, that means that something suffers, and I refuse to accept that the Bass Lessons and practice will be one of those things to suffer. I could tell those guys, give them one less chapter to read and I will give him one less Etude.

DG: When you did your last Zoom, there was a young lady who hadn’t practiced her bass in a year. Do you remember that?

RC: No, but continue the story, I’m interested.

DG: Okay. So you said to her that best thing for her to do was to take one Etude and finish it completely, and I thought that was such an incredible response, because you know, when you’re home alone all the time, you’re like, ‘oh, I’ll read this. Oh, I’ll read that.’ But that doesn’t mean that it’s going to be perfect. And your point was, ‘I don’t care if it takes an hour, an hour and a half to get back into what you’re doing, practice one a day and get it perfect.’ I just thought that was fabulous.

RC: Well you know, I’m not above doing it myself. When we were traveling, remember that word ‘traveling?’ You know when we went on the road, I felt like the guy with a stick on my back and bag on the end of it. When I get home my job, at that time we couldn’t take our own bass on the road and I would work with either ‘the bass de jour’ or we decided to take our own fold up travel bass my job when I got home was to take my bass out of my case and practice an hour on an A scale until I got it perfectly. It didn’t matter how long it took, it didn’t matter how awful it started, I just knew that within an hour, I had to nail this specific scale and it wasn’t just for the discipline of doing it. It was to know where my bass had those notes located.

And we have different basses: the curvature of the strings are different, the character of the fingerboard, is different, the length of the fingerboard is different, the height is different. The kind of strings are different. All those factors are in the way of it not being my bass, but no one wants to know that it’s not my bass. They hired me to do a specific job, which as the leader in this case to lead a trio or a quartet. To make that work, I need to have a certain skill and a certain understanding that this is not my bass. In the meantime, my focus is can I make this bass feel like mine? When the gig is over my job is come back to New York, of course, and how quickly can I say ‘hello’ to my bass, understand that this is what it feels like after not seeing it for nine concerts or eight concerts in terrible conditions, basically. So when I tell her to do that, I’m not above acknowledging that rule myself for different reasons. But the same effect is in place for discipline. And the outcome that we hope is a result of this new introduction to being disciplined to get some done for her.

DG: It’s different for us primarily electric players, we put it on our shoulder and then put it in the overhead of an airplane?

RC: Years ago when I was working, my first trip to California with Bobby Timmons, he was with Art Blakey at the time, he just left Art Blakey to put his own tour together with me and Tootie Heath, I found out that the process that Art Blakey used to use would be to get to the airport at the very last minute and walk out and talk to the attendant to let him walk out to the airplane with the bass and put the base in the seat because it’s too late to do anything else with it. Well, that worked for a couple of times with Bobby Timmons but that kind of wore out real fast. Of course, as the planes got smaller, and became more efficient, the bulkhead disappeared and so did the people who were sitting behind the bulkhead. So we were back to that no bass on this tour, you had to take either something that was there or bring a travel flyaway bass, you know, but again, when I got home, I had to take my bass out of my case and find out does this still work the same way as it did nine concerts ago? And how quickly can I get back to saying hello, how are you?

DG: I think it’s so important, whatever the reason is, whether it’s that young lady wanting to get back into it or trying to practice. Of course, it’s different with an electric instrument, but you still want the long tones, you still want the articulation to be perfect. So the similarities are there as well.

RC: Yes, absolutely. The difference is you can see where you’re going, You know you have those frets and diamonds on your fingerboard so I’m hoping that my sense of how far it is from A to Bb is the same in most cases, you know?

DG: Yeah. I want to show you something. I bought these two books in 1971 at The Bumblebee Bookstore in Boston right next to the Berklee College of Music.

RC: Wow, I didn’t know that MJQ was publishing Ornette’s music. I just saw the publishing at the very bottom of the book The MJQ Publishing

DG: I think this was 65 Let me check. Actually, it’s 68 MJQ Music 200 West 57th Street and back then, you know, obviously all we did go into music school is practice, practice, practice practice. You remember John Neves? For my first private lesson with him, I walked in with my P bass and he goes, ‘Mr. Gross, the electric bass is not a valid musical instrument.’ It was part of that jazz police kind of thing where I guess for a lot of folks, it was a difficult thing seeing all of their hard work and practice sort of being sidestepped to rock music.

RC: I don’t know that. I don’t know that feeling. I never had that. I never felt that Jaco was a threat to my livelihood or James Jamerson or Steve Bailey, my dear friend Victor Wooten none of those guys. I had a long talk with Monk Montgomery many years ago after he left Lionel Hampton’s Band about what he did with electric bass. Those guys are my friends. I’m a fan of the people that watched how they have taken an instrument that was kind of called a pork chop in the slang of the instrument and made it a very serious musical event. When you hear the results of the effort. Bootsy Collins, all those guys, man they made the bass do something. So when those electric guys got on the scene and became more visible and they brought their influence not just to the music, but to the use of amplification, gear and the whole one environment. I applauded those guys.

DG: I was going say is that I thought you embraced the instrument, I guess the first song that comes to my mind is Red Clay by Freddie Hubbard on CTI Records. What a great bassline!

RC: Yeah, well, you know, that only got there because Freddie didn’t bring the part in, I came up with the intro to it and we got lucky and struck the right note at the right time. We hope that while they don’t remember the intro, they won’t forget it either.

DG: That’s certainly true. I wanted to talk a bit about your new book “Chartography” because it’s a phenomenal idea!

TS: Why did you pick the tune “Autumn Leaves?”

RC: First of all, everyone knows that song and every jazz player primarily has played this song at some point in their career however brief their career was whether they work all day at the optometry shop or at a deli on weekends, someone calls that song. Having decided on a process to better show what I think a valuable transcription can look like, that song provided me an excellent format. As that was the first tune that the Miles band played nearly every night for five and a half years it gave me five and a half years of choices to make this process as I envisioned it come to fruition. It was easy to pick five versions because it was the same personnel. It was a perfect storm for a great kind of analysis.

TS: A controlled experiment.

RC: Right again. With the same band with the same song with the same basic format. Templates changed depending on factors that were out of our control, which is part of the experiment. Sometimes we get to the gig right from the airport then onto the bandstand and on those days, we never had the same instruments they were all different piano different drums, different basses, we sometimes had no soundcheck. For us, it was really the essence of a perfect place to try these experiments. There were a lot of help from Dave Baron and Leon “Boots” Maleson and we figured out that this is a way that makes my view of making transcriptions more valid.

In this case, not only do you have a bassline, but you have a whole song to a total of in this case, total four choruses, times five different performances, at the beginning of each sheet of the new transcription is the QR code which allows you to hear what you’re looking at. So you can actually see how the bassline not only evolves for the four choruses, but four choruses, times five versions. You can hear how Herbie and Tony and Miles are waiting for this next bass from the guy who’s hiding behind a palm tree where he’s going to take them and it’s a great view of that transcription that’s completely complete. It wasn’t just a bass line on page three of a transcription book.

My question, which is why I came up with this view of this transcription book is you can see how the line started out. You can see how it affected the band’s process. You can see how the bassline developed over four or five times. And even better you see how the band responds to this information. When you hear Herbie not play a chord but he plays this chord because he remembers the last time or I play a six eight rhythm in January and in March we do it again but Tony’s always plan three four against my six eight, and Miles is drilling because I’m not quite sure where we’re going but he knows that I’ll find one somewhere.

So the perfect storm for me. And this is why I hope that not just bass players buy this book, I hope piano players will buy this book so they can hear how Herbie is affected by how the bass player plays, and they can hear how Tony is waiting for my next rhythmic move and he borrows something that I played the last concert with this song, and he uses that information because he hears it coming again and how he responds. It’s that kind of group transcription that we happen to stumble on as you’re trying to make the bassline as important as we think it. I think it is a very valid way and I would like to think that bass departments and bass camps wherever they are get involved and you could have 40 kids trying to play Jazz, give them this book so they can see some additional options that no one can show them unless they have this type of transcription method.

DG: What I also found was a complete embrace of modern technology with the QR codes. Think about how many records I have destroyed by putting a quarter on top that’ll slow it down just that much. Well, if I put three quarters on top, it will get even slower but the pitch is going to change. You have come up well, quick. That’s it. I can watch this a million times.

RC: Yes. That’s fantastic.

DG: How great is that? And when you look at the first version, all right, the 1963 version, at Monterrey, you’re doing your first chorus. And then the second chorus, we go from a C minor seven and the next chord is a C sharp diminished. So not only is a bass player learning, ‘oh, I go here, then the important concept to me was, why is it a C sharp diminished? Okay, so that’s an E. So that’s, oh, so that’s why we’re doing that.’ And I think that’s even more important than the actual note. What I am saying is there’s an incredible amount of theory there. There’s so much to learn just from bar one, to bar two.

RC: The original changes. Yes, we just got it from somewhere. And we all would agree where the somewhere was, which is also important. You got to know where I’m starting with them. And then with me, so that when my options are made visible, they understand they’re based on this version of these chords that we all agree on are good changes. You know, my job as a bass player is to play the kind of chords that make the horn players go like this with their eyebrows, you know, and say, oh, man, now what?

DG: I also think the fact that you took the same song over five years. To hear from ‘63 to ‘68, just take those two and listen to them first, and then Oh, wow. Where did it go in ‘65 and ‘66? I’m excited about that. I’m fascinated with it. For me personally, I’m going to go back and listen to a lot of other tunes and do the exact same thing. Now just like you, I’m not going to write them out. The last thing I ever wrote out, Keith Copeland had me do the rhythm to the entire Ahmad Jamal version of Poinciana. Although I’ll tell you, I did write for Downbeat’s Workshop column, a transcription of Eric Dolphy’s solo bass clarinet performance of “God Bless the Child” and about a week into it, I called Downbeat and said, hey, what if I took four, four bar phrases, and then show you how you can use them as an educational piece? They said, ‘Oh, that’s a great idea.’ I hate transcribing!

RC: Yes. That is a tremendous work. I know that piece. It’s really hard. Speaking of transcriptions, one of the things that I think bass teachers who want to show the kids basslines, they will show them a transcribed baseline and have them play it through the keys. And that couldn’t be any worse thing to do. First of all, Dave, I’m not sure how many bass players, are going to have the kind of skill level literally to play a Paul Chambers bassline or a Ray Brown’s bassline, I’m not sure they can find out where the notes are located, given the difference in skill level that these beginning bass players have.

And the third thing I worry about is that if they learned this bassline in the key of B flat, or D flat, for example, if they transcribed a bassline from Oscar Pettiford if they don’t do the song in that key then that bassline is useless to them. That baseline won’t sound the same as G or C. So it’s doing them a disservice that is consuming that valuable time and having them misunderstand this line that just transcribed in and of itself is not transferable, you know?

DG: Makes perfect sense and that’s why when someone calls “Autumn Leaves,” it’s going to start on a C minor. That’s just the way it is. So why would you want them to do it in let’s say G flat?

RC: I mean, just, especially if they start getting involved with other guys who are equally harmonically curious and who are willing to accept a bass player’s set of notes as being something really worthwhile for them to investigate, they aren’t going to put it in the key that limits that bass players options because they want to find out what he can do for us tonight when this theory class opens, you know,

DG: You know, one thing I would suggest with the “Autumn Leaves” thing, your version on the Chet Baker record.

RC: It was with Paul Desmond?

DG: Yes. “She Was Too Good For Me” That should have been the next transcription because your tone! That’s a beautiful recording and that whole album is just a beautiful album, too.

RC: One of the things I have always kind of tried to tell myself in my head, when I get to these gigs, even if they’re not my band kind of gigs, you know, before I do my harmonic experiments and go into my laboratory, I want the band leader and the guys in the band to know that I really know this tune. I really know how it started out. And so by the third chorus I hope I’ve convinced them enough and that allows me to play first note on Autumn Leaves as an E flat. I’m not lost. I’ve got a plan here.

DG: Something that you said in the Tim Wells documentary, “Walkin’ the Changes,” ‘I’m not picking notes out of the air like I’m picking apples, I’ve a plan in my head!’ I’ve co-opted it. I do give you credit.

RC: I love apples, too. And again, one of the things I hope with this book is that kids can see how your notes do in fact affect everything above it. You know, it isn’t from the top down it’s the bottom up for us?

DG: That’s exactly right. That’s great. I think you have fun with your mistakes.

RC: Better mistakes. Yeah, great ideas. You know, one thing that I hope that this book, this Chartography also encourages the bass player to understand that they have always have choices, they will never run out of things to do. But that depends on them remembering what they played. We all have our little crips, we used to call them “bags” back in the old day. My hope is that when they look at this book, they will question how do we get there other than we got there. Well, one was we remembered the things that worked and develop those things to another level. That’s critical for us.

DG: This book, really goes in line with your other books “The Comprehensive Bass Method,” “Making the Changes,” everything fuses together. There was something else that struck me. When you were starting out and when most people pre-YouTube let’s say or pre any of that stuff, you started with the Simandl book or Edouard Nanny or something like that. Do you find that the modern-day bass player learning jazz doesn’t get into the original Simandl? In other words, they start with jazz. They don’t do Simandl, because I know you’re a big proponent of foundations.

RC: Sure. I know where you’re going with this and one of my my “second craw” is I think bass teachers and Jazz Bass teachers generally don’t increase the student’s skill level as they become more and more involved in working more gigs. They want to know how to play dude, the Count Basie bass line on the bottom, that’s always good, or things, tricks that they have learned that they can show this basically but they don’t increase the kids, the bass players skill level that will allow him to find his own way physically on the bass and that limits his choices because he can’t find the notes that he’s starting to hear or the piano player who likes Bill Evans or Herbie Hancock has got a new voicing that they won’t find on the Ramsey Lewis record or even an Ahmad Jamal record and his notes, you got to find a way to make that new piano voicing or the new guitar voicing work unless he can find these notes by knowing his instrument he’ll have a difficult time satisfying his curiosity and the band’s hiring him because he’s not playing the right notes because he can’t find them. And I say that not to jump on bass teachers cases necessarily but to encourage them that they’ve got to find out how the bass works better so you can tell the kid this bassline is nice but he found these notes because he was listening this way and he knew that this note was F on the D string but it’s also these notes across a string. They have to know that really basic, there we go again with one string this time, basic info to make him or her have the choices that the music is presenting them.

DG: Somewhere in your biography, “Finding the Right Notes,” which is another book everyone needs to purchase, you talk about going on a gig, and everyone was doing some modal stuff and you went, ‘oh, I know that I learned that in my Classical Studies’ and it just seems we’re getting away from the basic foundations. YouTube has become a bit of a crutch in a way I can learn these half a dozen songs and boom, I can get out and do a gig versus I can learn to play my instrument.

RC: They see the results before they do the work that goes into it. They see a Ray, they see Christian, they see all the good guys who really play the bass well and they don’t understand that those guys started with Simandl page nine, this is a bass, these are the open strings.

DG: Even back when Rufus Reid’s book, “The Evolving Bassist, a great book except the part on how to hold the electric bass…those pictures.

RC: One of the things I tell the parents who are very concerned about their daughter and son taking the string bass, the way it costs, I tell them I heard about this joke about string bass. There was this young kid nagging his father to be a musician, he wanted be a bass player, because he saw it was loud, did all the things, so his father finally

buys him a bass. So he goes to school for the first lesson, and he comes home about an hour later and his dad says, ‘well son, how was I was your bass lesson today?’ He said, ‘well, it’s okay.’ The next lesson he goes a week later and he comes back hour and a half later and the father says, ‘why are you late today?’ He said, ‘I learned names of the strings today.’ His father is very impressed because he says he sees musical progress. And so that third week, he makes his way to school and it comes back one hour and twenty-five minutes later. ‘So today I learned the strings E, A, D G,’ and his father is thrilled because his son made a start and read a little music. He goes to school for the fourth lesson and his father is getting frantic because his son doesn’t come home for two days. ‘So what happened to you?’ his father asks? ‘Dad, I had a gig!’ It has been known to happen. I think Tom and David, once a bass player understands the control they have over the music and how important their notes really are they can literally control the direction of the band, they will stop and say, how can I find these notes that are so powerful? How can I find these notes, if they are so powerful? Well, we go back to this, page nine in Simandl.

DG: Exactly. I remember I got Rufus Reid’s book and I got Simandl. And they threw in Edouard Nanny which was actually a little more painful because the book was too big for my bag.

RC: And in Italian.

TS: You know, you mentioned we were talking about digital media and YouTube and things. And just the fact that this book has QR codes, Ron reflect over the value of digital media now with YouTube and streaming services. Now more than ever, I have more access to jazz than ever before. It can also be used as an educational tool. We can go back and watch the masters. We can watch Paul Chambers, we can see the footage of this. Digital media is not only an educational but an inspirational on as well.

RC: Well, you know, all that’s true, but it still starts with a live performance between you and your teacher. And I think because we have so much YouTube available to us, it misleads these kids to think that there’s nothing to it that I can really do by myself. All the questions I’m asked whenever I do interviews and masterclasses one thing I’ve always said underlined that this bass player whoever he or she is, they need a teacher. I never say a bass teacher, but of course that’s implied. But then someone has to show them the instrument how to hold it, how to change the strings, what is the correct height for the strings. In Canada, I’ve seen bass players take their bass out of the case with the bass lying literally horizontally on the floor. And then when I saw that happen, I said ‘man, how do you, why do you do that?’

And he said, ‘that’s what we all do.’ I said, with the jazz clubs in New York that I know it’s big enough for piano, a set of drums and microphone stands,.There’s no place on this bandstand if that’s how you’re going to uncase your bass to make this gig because there’s no room up there. You Tube for all the advantages that they are for young people, they give them a false sense of history. Also, I think because they don’t see it, have they ever saw Paul Chambers practice? They never heard him have a teacher. They see this great wonderful Ray Brown. I think part of my generations, Christian McBride’s generation is to encourage you to hear those guys, but they started with page nine of Simandl and they admit it but again, I’ve never seen Oscar Pettiford live and when I moved to New York, he’d already gone to Europe. I missed out on that but at that time, there was no social media.

So guys like that, I wish I could see those guys and hear them play live and see how he held the bass and see how he found those great notes that he wrote for the bass perfectly like “Tricotism,” “Swing Till the Girls Come Home,” all those tunes perfectly written for the instrument. How did he play them? I want to see how he got those notes. Well, these kids today, they can see how I’m trying to find them. They can see how Ray Brown tried to find them, they can see how Christian McBride finds them, Rufus Reid, they can see how we find them. I rue I didn’t have the opportunity when I was their age, but I’m not upset because I didn’t see them. That just wasn’t the time of practice development of cameras and sneaking videos and all that kind of stuff.

DG: It’s interesting too, because my wife and I right now are working on a documentary on Slim Gaillard. Mark, his son is helping us with this and when you think about Slam’s arco technique, you know darn well, there was a Simandl book or something.

RC: Paul Chambers has listened with the first bassist in the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. You know that’s Slam Stewart on the Town Hall 1944 with Don Byas, fantastic.

DG: Regarding Oscar Pettiford I think “Deep Passion” may be one of my desert island tunes. Not only was he playing great bass, but his orchestration?

RC: He wrote Georgia Duvivier arrangements back in the day. A great arranger. You know, the bass collective, don’t just play the bass. We’re the last guy to leave the gig because we got to pack up the bass and the amp. We do other things to like write great arrangements. Rufus Reid writes some great big group arrangements, original, just lovely writing. So we do something else besides play roots.

DG: It’s a wonderful thing too! Once again you start on an E flat. I like that a lot! It’s funny too. Because if you really think about it with a seventh chord, the fifth for the most part is the odd note out, you can’t really tell, is it a major or minor, but that third, that third tells you everything.

RC: Yeah, speaking of my book, there is a story in there; one of the questions I am often asked in these kinds of talk events, ‘did Miles ever tell you what to play?’ because that’s reputation he’s earned over the years due to no one really knows what he talks about. They say, “Hey, man, did he ever tell you what to play,” and I tell him this short story. We were doing “Autumn Leaves” and I just had enough of playing the G minor for the last chord down to seventh going back to the top of the tune so I went to the fourth beat of that last measure and played a B natural and two or three bars away during the solo, Miles walks behind me and pulls my coat and says, “What was that note?” I said it’s a B natural to make that G minor chord a G7 a natural way to go to C minor – don’t talk to me because I can’t talk back to you and play at the same time. But it’s that B natural, that third you talked about, if everyone expects a G when you’re on a G minor…No, G7 man, go right to the top with a C right there, it’s perfect!

DG: How you look at it as a G7 I’m just thinking, Oh, it’s just a passing tone below. But it has its own function, it’s a third.

RC Absolutely. Yes and this is going on in real time. We’re thinking about doing another version of the book this time using a blues with the Miles band or something like that because they really got kinda outrageous, the harmony and rhythm. You can’t be walking but so many ways without going outside some kind of way.

DG: How long did that book take? How long did your “Chartography” take?

RC: I guess about four months.

DG: Now did you have the concept that, we’re going to have the songs we’re going to have the various harmonies, we’re going to work it out. Did somebody help you with the quote unquote technical aspects of things.

RC: I had someone to help me transcribing it.

DG: I mean for instance, at the very beginning in your key to it numbers occur. The three over four rhythmic idea you had.

RC: That kind of stuff is the combination of everybody. I had Dave Baron find out what’s the best color they have on the book to get their attention given the amount of information on each page. Look at page three where you have three different colors on there that have significant impact on what you’re going to hear. And how dark is it? And when you make multiple copies, is it going to fade out? And are they easy to go back to the first page and say oh, number three means that number four means that in this new E flat seven with this different kind of color, that means that. Those decisions were a group decision. Then we have a chord change and we say what it is and we will try to figure out what’s the best color for the different harmonies we use and what’s the best color to outline what rhythms curve somewhere else so they can go back to the charts. So that kind of physical manipulation of information with a group a very, very actively equal opportunity, choice words and necessary point of view to make this kind of thing come together

DG: The reason I asked is I think book two is going to be a lot faster, because you have all the components in place.

RC: In theory, but it depends on what the tunes are going to be too.

TS: One of the things I want to ask you, your career spans the record album, the 8-track, the cassette, the CD. I have a record collection back there where you’ll find “Pegleg,” “Dear Miles and “All Blues” plus other records. Now we’re in the streaming world and I know some of your records didn’t come out in the United States, you recorded for Japanese label. David and I like would like to know, do you think it’s the best of times or the worst of times, because now you as an artist can go directly to an audience, you don’t have to sell your record or convince your record company to put something out. So is the power all in the hands of the artists now?

RC: Well I’m a little concerned about that, because the audience has a chance to disrupt my story. I make a record, I have a plan in my mind. I pick the right keys, the right order of songs, the right mix. To just pick track three of my record that destroys my story in theory. And I would like to have them hear how that third tune fits into the whole record. So that’s gone out of my control now that the streaming is kind of taken over that part of the presentation.

TS: Playlists are a fact of life now.

RC: Well there a fact but I’m not sure of life but it’s clearly a fact. A fact of life is that they’re underpaying us. That’s a fact of life and there’s a movement now that’s starting to get some momentum that the powers whoever they are that be, I call them the non-stripers, have a chance to make to pay a lot more equal than it has been. Many within the past few years, musicians thought the solution to not getting the royalties, whatever they would amount to, would be to put their own record out. They had their own labels, but that was fraught with as many problems because they didn’t pay the guys who were publishers of the songs that they recorded. They were not originals and that itself had issues. That was not a complete solution because the solution is bigger than just having your own record label.

TS: You still have distribution.

RC: What does that really mean? Not just distribution. You record a Herbie Hancock tune, you record a Rodgers and Hart song, you record a Miles Davis song. Who pays those guys? The publishers, the writers, they’re supposed to get paid! And these independent guys who were doing this, it never occurred to them that it is not pure profit, you’ve got to pay all these bills after you make the disk. It’s not just going into the studio. Streaming, it seems to make music more immediately available, therefore the order which is made that they had a chance to listen to a record which is out of the order which I recorded it because it’s a package for me not a book and you starting reading on page seven, Who does that? Having said that streaming is the way it is and we just hope that some kind of way we can balance out the clearly unequal payment process. We can kind of get on with our business of making music and not be so concerned with them taken advantage of us one more time.

TS: I know you commented in your book, “Finding the Right Notes,” about the aesthetic of the album, whereas the CD medium, I believe you commented was a little bit too long and LP was about 37-40 minutes where the CD extended after seventy-five minutes, which might be too much information. Of course, it’s the whole the beauty of the artwork of an album cover.

RC: One of the reasons I think that the CD length was detrimental to the artist was, I’m not sure how many artists of the younger generation, we could think of that could put together a story for seventy-five minutes and have everyone read every chapter. I haven’t seen that. I’m sure someone has done that but it’s difficult. I’m sure nine guys will say hey man, I did that. But again, if you are looking for standards, no more than thirty-seven minutes, man that’s it and the music is incredible, not just that it’s sold a lot of records. But the fact is, every track has value and every track is a strong statement. This has been new for its time, that’s a given and I’m not so sure that the record that is sixty-five minutes long has the internal where with all to make everyone want to buy this record because it’s got so much music on it, total music. The guys in Japan said, “Mr. Carter don’t make a record no more than fifty minutes that was our limit.”

TS: We were talking to Rudy Sarzo and he mentioned his disdain for Greatest Hits albums, because like you said, Ron, it was disrupting the story.

RC: Sure. I guess it’s okay to have your music put out whatever the form because everything is changing and being eliminated and made smaller along the way. We’re concerned about how many jazz clubs are going to be in action once they open that up, whatever that timing means. So that’s maybe one or two less locations for us to experiment. Our laboratory is getting smaller and smaller, and to have a greatest hits kind of thing, it really dilutes our worth, our l musical worth because it’s in a wrong place.

DG And I think nowadays, the record companies, with no disrespect to young people, but when you have bean counters, basically handling everything… At least in the 70s and 80s which were my mostly gigging years, the A&R people and the business people were passionate about music. Now we’ve gotten to the point where we have accountants doing the music, it’s not the same thing.

RC: I would add to that statement, a footnote saying that it isn’t just the bean counters but the people who are the producers. I’m not sure their historical leaning toward the background of this music has been carried over to the current view of the current people who are calling the shots who determine who gets to record, what’s on the record, that kind of stuff. I think those people are a different breed right now. I’ll give you an example; years ago, when they would do commercials, they would always have a stable of musicians, where the video guys would hire a real jazz player to hold the bass correctly, and the saxophone wouldn’t be held with wrong hands.

The practical producers knew the music. They knew who Coleman Hawkins was, they knew who Ben Webster was, they knew Trane before he was Trane. And so they wanted some authenticity to their project. I think the current budget producers they’re not so aware of that part of the music that the old guard, that the older generation was and they’ve kind of gotten another view of how best to present this music. Okay, that is their view. It clearly is in contrast to the influence that the producers had. Ahmet and Nesuhi Ertegun, Bob Porter, Esmond Edwards and George Avakian. That bunch of people knew the history because they were a part of the history. I think the current producers because they were not physically a part of the history, they’ve kind of decided that it wasn’t too much there for them to worry about because it’s past them.

TS: So Ron, to continue on your COVID intermission, let me put the question to you, what’s the first thing you’re going to do on a gig?

RC: I’m going to look around and say ‘where have you guys been?’ We’ve had some group conversations over the past year and a half or so just to get a feeling of how much we’re missing each other and someone was putting together a tribute to Chick Corea and they have eleven piano players to play some of Corea’s library. I was asked to to play one of the Chicks tunes and one of the piano players called me to be an assistant to them. And it was, yes, I can do that. And I think I can do the song because I recorded with Chick at some point, back in there back in the day. It’s just nice to be out in the street with a live musician, a real situation of a studio with some real recording engineers who were really doing this job right into this tremendous awakening of those kinds of feelings that we were all suppressing for 15 months or so. It is a great thing to do and the piano player said we gotta do this again. Yeah, five months from now.

DG: I must say the Village Vanguard does a loving job of streaming, even though no one’s in the audience, at least the music’s out there.

RC: They have a great sound. Those guys know how to do it. Yes, absolutely. It’s not like being there but it’s as close as you can get and not be there.

DG: I think the benefit for that is now that they know how to do the film shoot and they know how to do the recording for it, when people are in the audience, we hope people who aren’t in the audience are going to be able to benefit from it too. So I think there will be a good thing from it.

RC: It helps because they’re nice. And they’re all nice kids. I call them kids because they’re 25. They’re kids to me. They’re really nice people who care about the music, and they care about the visual presentation of this music.

DG: Yeah, it was obvious. I’ve watched a number of them. There was a great one. Well, you’ve worked with Bill Frisell. He did a great one with Thomas Morgan. It’s so crystal clear to see and crystal clear to hear.

RC: However, that will not be the solution to this music. We cannot survive on that. It’s a nice thing to do. We need that interaction, but it will not encourage that presentation too many more times once the clubs open up. A special event? Sure, because you can do it. But I think that, say you can have one night a week streaming, don’t do that no, don’t do that.

TS: Ron, how do you explain to people what it’s like to not play a gig for 15 months?

RC: I just tell them what I’ve been busy doing. I teaching 10 private students online. I’ve worked on that Chartography for three months, plus other books. I’ve accepted that I can’t play with them until it’s okay to play with them, and I understand that, that decision is completely out of our control. We all of us, the jazz community, in this case, have lost so much work and so much of a chance to experiment.

One of the things I missed most of all Tom and David is not having to make those decisions. I have to worry about the tune, the order the

speed, what key, the solo, who solos, how long do they solo. What happens if the audience doesn’t respond to the song I want them to respond to? For 15 months I haven’t had that grief, which is a lovely part of being the bandleader. So, as of right now, I’m enjoying taking the garbage out on time, going through the laundry, walk to the Post Office, you know, that kind of stuff. And now, come September, when Broadway opens and New York starts to get more busy, those pleasures of house being, will be limited because I’m out there doing what I used to do… Working. So I try to explain that sense to people when they ask me, “Well, what do you do? How do you feel about not working?” And when people ask you, “when you are not working, what do you think about? You know, I miss being responsible, but I have other responsibilities now that I’m responsible for, and I don’t shirk those at all.

TS: I think there’s going to be a tremendous response once we finally can get back to the clubs.

RC: Absolutely. It’s going to be great, because everyone, everyone misses it. For those who didn’t get out, who were not jazz fans, but to go to a club, they missed that kind interaction. Because, one thing that’s great about New York, you can get to hear jazz anytime, any day, even if you don’t make a point to go hear it. There it is. Well, for fifteen months, you’d walk down the street and you hear this… (Ron makes a point of not talking…silence)

TS: Do you have anything specifically booked beginning in September?

RC: If I say I do, it’ll be canceled because Cuomo will say it’s too soon. Hopefully he’ll get this issue straightened out but I can’t say where I’m going to be other than practicing that damn C major scale again another day until I get that sucker right?

DG: Ron, I hope you had fun.

RC: I’m still sitting down enjoying the conversation. One of the things that I’ve noticed, guys is that when I get certain phone calls from people, it’s because they want to talk to a different adult. And right now, I’m enjoying talking to a different adult.

BONUS

NOTES FROM AN ARTIST/TIPS FROM THE TOP: Ron Carter Chartography Interview w/Special Guest Dave Swift

POSTSCRIPT:

Now that you have read throw this interview, I suggest two things:

1-Read it again! I have not only edited this for our radio show but transcribed and edited it for this article.

Each and every time I have listened, I have learned something new.

Mr Ron Carter is the “Total Package!” The epitome of class, refinement, thoughtfulness, erudition. Tom and I are both humbled and honored to have had the opportunity to interview him!

Lastly, “Notes From An Artist,” our podcast is archiving all of our interviews. To listen to this one go to: notesfromanartist.buzzsprout.com

While there, you will find many others that will be of interest.

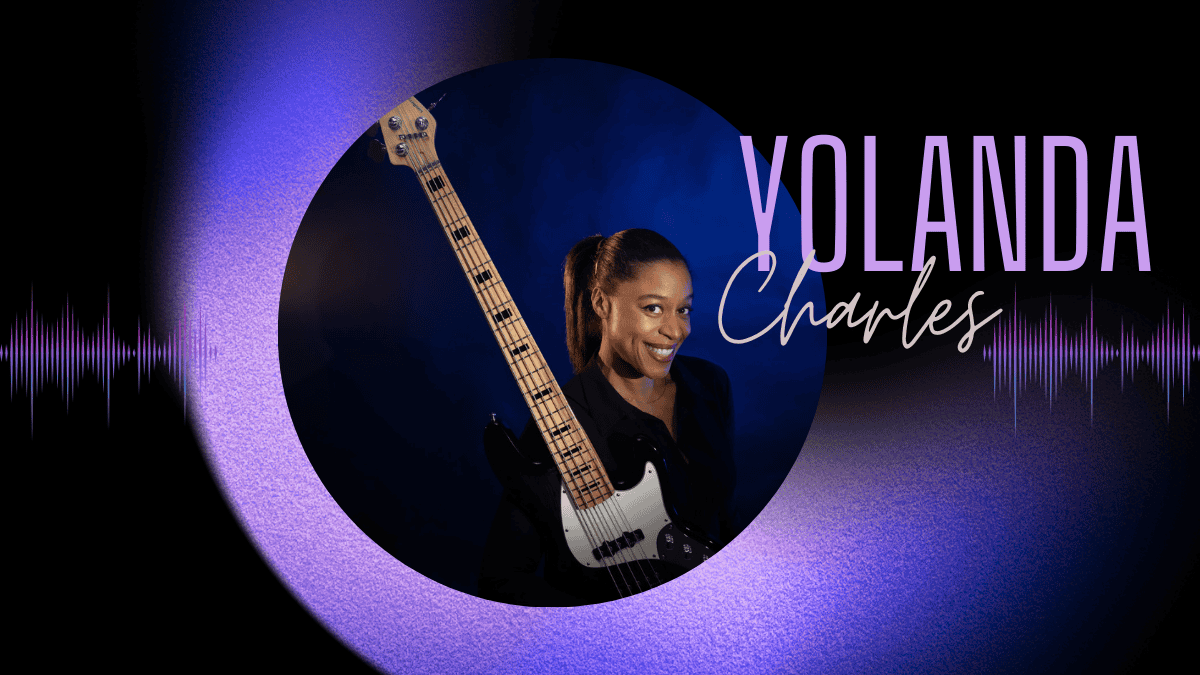

Cover

Yolanda Charles, MBE – July 2024

By David C. Gross & Tom Semioli

“I’ve never heard of Yolanda Charles…who is she?”

Such was the retort I received from my Notes From An Artist co-host and dear friend David C. Gross upon my suggestion that we invite Yolanda Charles, one of my favorite players, on our podcast – radio show. Two bass players with a seven-year age gap can sometimes forge a world of difference, which our listeners detect from time to time from our on-air banter.

Cover Photo Courtesy, Giuliano E at Graphik Vision

I have learned much from my partnership with my elder David – who looks, thinks, dresses, and acts much younger than I do- such as; the hidden merits of the six-string bass, why Mile Davis’ Bitches Brew is indeed monumental on levels I was not aware of, and the best entrees at Mamoun’s Falafel on the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

Oftentimes I educate my homie on the players who came to prominence in the 1990s – the decade wherein Brit Pop was my writer’s beat. I received my review copy of Paul Weller’s Live Wood album in late ’94 or thereabouts. First move every bass player makes when receiving said product is to check the bass credits! I didn’t recognize the name. A compendium of performances in support of the Mod Father’s then latest Wild Wood album, I’d never heard of Yolanda Charles either. I became a fan after the first listen – the combination of rock and roll and soul never fails to captivate this writer.

Yolanda is that rarest of players who fortifies her bandleader and simultaneously makes you aware of the instrument regardless of the supportive role. Dig Ms. Charles cutting through the beautiful bombast of Robbie Williams’ Live at Knebworth (2003). Her work with Squeeze on The Knowledge (2017) rendered a new coat of (ph)funky paint on the pop purveyances of Messrs. Chris Difford and Glen Tilbrook. Nice work if you can get it, and she does.

My choice Yolanda deep tracks/albums make for a fine playlist: Aztec Camera “Sun” (Frestonia), Deep MO Funk in the Third Quarter, Marcella Detroit “Boy” (Feeler), Mick Jagger & Dave Stewart “Old Habits Die Hard” (Alfie soundtrack), Mamayo The Game, Workshy “Finding The Feeling” (Coast), B.B. King & Friends with Roger Daltrey “Never Make Your Move Too Soon” (B.B. King & Friends 80), Misty Oldland “A Fair Affair”(Supernatural), Project pH “No ID,” “It’s Not a New Thing,” and “Hey Now,” to cite a select few. Get to work!

So, who is Yolanda Charles?

She’s a bassist, composer, bandleader (Yolanda Charles’ Project pH, pH Instra-Mentals), band member (Jimmy Summerville, Hans Zimmer…), educator/mentor (East London Artist & Music, Institute of Contemporary Music Performance, Royal Northern College of Music, Trinity Laban Music Conservatory), entrepreneur, musical collaborator, poetess, novice gardener, and recording and performing artist. Impressed? In 2020 Yolanda Charles was awarded the MBE – Member of the Most Excellent Order of The British Empire for her services as a musician in the United Kingdom. Bass Guitar Magazine crowned Yolanda as the “High Priestess of Funk.”

Here are select excerpts from our conversation which can be heard in its entirety on Notes From An Artist podcast available on Apple, Amazon, BuzzSprout, Spotify, and wherever podcasts are podded!

TS: David, we have royalty in our presence, tell us how you came to be recognized with an MBE.

YC: I love it, it’s great. I accepted the award – you’re asked first if you would like the award, and some people do turn it down because of the political connotations. At the time, I was confused as to why I was being given the award, because I thought those sorts of notices are given for public deeds and charities – and I’m not known for any of those things. I have had quiet activities that no one would know about that help local communities…and someone thought that I should receive an MBE! I guess they did a search on me, to see what my presence is like online – to see if there are any associations or incriminations… and I came up clean man! (laughter)

TS: Your solo project works under the moniker of pH – as in ‘pH’ which is the measure of acidity in water. Explain the origins…

YC: The name is representative of balance. There are lots of ways you can view it. I was looking to spell ‘funk’ but I wanted to avoid the ‘f-u-n-k’ spelling. And I like people to wonder what the ‘PH’ stands for. It also gives me material to find titles for my songs. For example, we have a track called ‘Acid Test’ and stuff like that.

DCG: Back in 1961 George Russell had a tune and an album titled Stratusphunk – and he used the ‘ph’ spelling.

TS: Let’s talk about Project pH – a jazz, funk, soul, fusion collective which includes Nick Linnik (guitar), Hamish Balfour (keyboards), Nicholas Py (drums/percussion); and vocalists Paris Ruel, Adeola Shyllon, and Carmen Olivia, among others. You’ve supported more than a few notable bandleaders – tell us about your approach.

YC: Creatively, I write a lot of the material. I explain to the band how I want it to go and I welcome their input. I don’t usually bring in a finished piece of music because I think if you’re going to work with a band its important to have their voice in the sound.

Sometimes we have a little bit of a tussle over chord changes – but we don’t fight over the basslines!

DCG: The chord change doesn’t change until the bass player makes it so!

YC: That’s right! (laughter) Recently I wrote a ballad on the bass, when I compose that way, I write the bass and the top line and I give them space for a bit of color. It’s fun to hear their ears take them, sometimes it’s not always where mine are and I like that. I get a fresh angle on something I thought I knew really well.

I think my reputation is a bit of a ‘whip-cracker.’ I’ve worked in the pop world, and everything in that realm is restricted. Sometimes you have musical directors that are listening to every little bass fill. And often they don’t want to do anything apart from what is on the record. If you play one extra note you’ll get a stern look, and if the keyboard player slightly changes the harmony – put the 6th in or even worse does an extension, a 9th or 13th they get fired.

I’m more lenient than that, we’re freer because pH is jazz-flavored. I make the band work on various sections of a composition until I’m happy. Sometimes I like the music to be really tight, other times I want the ebb and flow – so I use my body and my bass to conduct.

DCG: In a way, the bass player should be the band leader and the musical director – we are connecting the rhythm and the harmony.

YC: Absolutely. The role of the bass player in a band is the connection between harmony and rhythm. There is also something about the character of a bass player. Some of it is funny, like in ribbing someone or ‘taking the piss’ as we say in England. In a real sense, I think your character attracts you to the qualities of the instrument.

Or maybe, your character takes on the qualities of the instrument. Maybe all those guitar hero ego monsters – if they exist – get turned into that by the nature of the instrument! Who knows which comes first?

TS: When you were working for Paul Weller, he gave you ‘advice’ on how to position your bass – how did you adjust to the adjustment?

YC: I held the bass way up here (Yolanda positions her instrument beneath her neck, bow-tie fashion) because it’s easier to slap. When you drop the instrument down, you have to alter your technique.

I had to agree to be in Paul ‘The Modfather’s space with my 1980s tastes because he was definitely more of a 1960s guy. Luckily, I didn’t have to slap on the job – imagine doing that on a Paul Weller gig! (laughter)

TS: I would love to do that!

DCG: And you’d get fired!

YC: Check me out, I was 22. I was a kid. It was quite intimidating. I think I would handle how to hold my bass and position the instrument differently today!

DCG: On that topic, Billy Sheehan said to me, and it made more sense than anything; when you are sitting down and practicing, why would you change that because when you stand up – you have to physically reevaluate all of what you learned sitting down. Sit in position, get a piece of leather, cut it and that’s all you need.

TS: You use different muscles when you change positions.

YC: Yes. I also recommend my students to use a guitar footstool. Get the bass in the space that is right for you, sit with your knees akimbo, put the bass where it should be if you were standing, then stand up, and see where the bass should be on your body…

It’s a very personal thing. Getting back to Paul, that’s the thing about session work – it involves letting go of certain aspects of your character and personality. You have to allow yourself to be molded into the thing they want you to be. That goes for being a musician – stylistically. Even looks to a certain extent.

I had complaints from one female artist I worked for. From her management, not from her, that the most flattering colors that I wore … were banned! (laughter)

(Yolanda imitates artists management) ‘Er, could you just wear a sackcloth, please? And perhaps a bin back over your head?’ (hysterical laughter)

That’s why I advise my students ‘are you sure you want to be a session musician? Have you got the character for it?’ You have to be a team player and respect that you’re not the boss, it is a hierarchal situation. It is not a level playing field. You are hired help.

You have to kind of do things that people ask of friends. But you are also being paid a salary. And it’s really confusing. And you can get it wrong, and you can get fired because you overstepped.

You have to understand the politics of this stuff. Also, are you an argumentative type of person? Do you push back because you were told something by someone who does not have the best personal skills in the world and who might be making a demand of you in an unfriendly voice or using language you don’t like.

You sign a contract and the contract does not have a clause that reads ‘if they don’t speak to me nicely, I can leave…’

TS: The era of specialization on one instrument is over – how do you guide your students?

YC: They know. It’s funny, I made my first record in 2002, and I did it college industry style then. I created a website, and my own record label, but I did it with a few of the tools we have now. And I understood at that point I needed to have those skills. If you just make a record – you’ll be like all the musicians who think they’ve made a record because it never leaves the hard drive, or they press it and it’s in boxes for years and years.

I was determined to not have that happen to me. I kept the costs down by using friends’ studios, we produced ourselves… I was able to pay my musicians because I was touring with other artists. I pressed a thousand copies and I used the disc as a business card – like the way people use the web now.

Yes, it is entertainment for others and a way to make money by selling them at gigs, but for a musician, and other creatives, it is the way we tell people who we are, and what we do, and let them know that we are available.

Some people see social media as showing off, or being a narcissist, but it’s to let people know we are here, that we exist, and that we are available.

If you look at the artists I’ve worked with in my career, they are all in the kind of pop-rock territory. If I just stayed in funk and soul, I would have had a narrower career.

I was in a session with Dave Stewart, and he said, ‘so who is Yolanda?’ And I said ‘What do you mean?’ I told him I made a record and he asked me to bring it in. And I would never do that, some people are always hustling. A few days later he told me that he’d listened to it and he gave me a bunch of pointers. We were just talking as musicians.

When I first handed it to him, he said ‘Oh, so you’re not just a bass player…’ And I didn’t really understand what that meant at the time. He perceived it as me being an all-around musician as opposed to an instrumentalist purely. He saw that I could arrange, write, record and I could organize. Later, he hired me as a musical director for his band. It was because I had proof that I could do all these things. That qualified me, as well as the fact that we got along in the studio.

Making records is important if you want to put yourself out there – you can’t expect people to know who you are unless you tell them. How you tell them about yourself isn’t bragging. The gig with Dave Stewart led directly to me being in Hans Zimmer’s band. To me it’s kind of like chance and luck, however the opportunities for chance and luck only arrive if you create the conditions.

DCG: And now you can just give them a thumb drive!

YC: Yes, or you can simply send a link and they can see everything you do. People waste their time on social media showing, ‘This is what I had for breakfast… these are my new shoes…’ Don’t bother with that stuff, you don’t know who is looking. And most times they’re not looking at where you bought your shoes, they are looking at what you write, what do you sound like, what are your lyrics, what is your creative space?

TS: How do you mentor for success?

YC: People ask me for advice in the form of ‘Can you help me.’ My first response is ‘What do you want? What do you want to achieve? What are you actually looking for?’ And very few can answer that question straight away. Is it ‘you’ with a top-paying gig? Is it ‘you’ with a certain amount of recognition? Or sales? Or followers? Is it about making the best record you could have made? Look at where the compromise has to happen.

Maybe the best music you can make does not equate with a huge following. You have to hone it down to what is your actual core. You can’t have it all. If you want to make a great record, what does that entail?

If you really like atonal music – okay. But I’ve got something to tell you about that. Large followings do not come from artists who create atonal music! If you really want to make a record that’s a bit out there – okay! But you have to let go of some other ideas you have at what success looks like.

True success might mean you make records that don’t sell a lot. But you’ve identified what your actual real ambition is. And once that is acknowledged, once that is said out loud, strangely what happens is that kind of peace settles in. ‘Oh, I get it! I know what I want now!’

With that approach, it’s easier to not be envious of a kid who can play five chords and has ten million followers. You don’t have to bother with that because this thing you’ve created fully focuses your attention. So, what’s going on ‘out there’ does not really matter anymore.

A big part of happiness is really knowing what you want.

For all things Yolanda Charles, check out https://g4dz.com/

Bass Videos

Will Turpin, Celebrating Collective Souls 30th Anniversary – June 2024

Will Turpin, Celebrating Collective Souls 30th Anniversary – June 2024…

I am sure many of you will remember my chat with Will Turpin in 2018 when he released his solo album Serengeti Drivers.

We had a chance to get together again as his band, Collective Soul, is celebrating their 30th anniversary and releasing their new album “Here to Eternity”.

Join me as we get caught up on the new album and all of Collective Soul’s projects, the details about his very own Real To Reel Studios, how Will gets his sound, and all the cool plans and projects going on soon.

Here is Will Turpin!

Photos: Cover, Derek Alldritt | Video Photos, Derek Alldritt, Lee Clower, Brian Collins

Featured Videos

Follw Online

FB@ Real2Reelstudios

FB@collectivesoul

IG @ Willturpin

IG @collectivesoul

Cover

Guy Pratt, Not Your Average Guy – May 2024 Issue

Guy Pratt, Not Your Average Guy – May 2024 Issue

For me, the bass is like this poor dutiful, loyal kind of wife. I go off and have my affairs and run about town, then I always come crawling back to her… Guy Pratt

By David C. Gross and Tom Semioli

Photo Courtesy – Cover Photo, Paul Mac Manus | Promo, Tarquin Gotch

Most rock and pop devotees know the individual names, likenesses, and other “intimate” details of their beloved ensembles.

Everyone has/had their favorite Beatle… darling Rolling Stone… preferred Led Zeppelin, their chosen who’s in the Who – etcetera.

And even in those instances, the enigmatic lead singer and swaggering lead guitarist garner the most consideration in the public eye. Aspiring drummers, keyboardists, and bassists will naturally gravitate to their said instrumentalists. Civilians could care less.

In the case of the singular artist, it’s all about the headliner, and quite frankly, that’s just how the nature of rock celebrity works. It’s the name on the ticket that counts.

On rare occasions, the second banana gets peeled: Mick Ronson spidering beside David Bowie, Steve Stevens rebel yelling in the service of Billy Idol, Scotty Moore twangin’ with Elvis Presley, and Steve Vai shredding alongside David Lee Roth, to cite a select small number. “Very few are chosen and even fewer still are called…” to quote Warren Zevon who piled his craft with guitarist Waddy Wachtel in tow.

Rarer still are the sideman/session bass players who somehow catch the slightest edge of any spotlight. Motown legend James Jamerson Jr. was not recognized until long after his passing by way of the 2002 Paul Justman documentary Standing In The Shadows of Motown which was a surprising box-office success and consequently spurred on similar films such as The Wrecking Crew (2008) Muscle Shoals (2013). Even then, these studio cats’ time in the sunset as soon as the film credits rolled.

Other bassists in the strictly accompaniment arena catch a notable wave by the nature of their unique contributions to international hit songs – witness Pino Palladino with Paul Young (“Every Time You Go Away”). Studio ace Will Lee (for whom David C. Gross oft subbed), gesticulating in proximity to charismatic bandleader Paul Shaffer, was visible to millions in his four decades with Late Night with David Letterman, and The Late Show with David Letterman. Rarified air indeed.

Which brings us to Guy Allen Pratt. Born in 1962 in a place called Lambeth London, Pratt came to the instrument in the funky 1970s when bass, thanks to improvements in audio and recording technology, could actually be heard on the radio and on hi-fi record players of the day. Rather than prattle on about Pratt’s formative years, we highly recommend his hysterical autobiography My Bass and Other Animals (2007) Orion books.

David and I love talking to our record collection on Notes From An Artist. Guy not only talks to his record recollection on his podcast Rockonteurs with co-host Gary Kemp of Spandau Ballet fame but he’s played with them! You (lovable) bastard!

Guy’s credits on stage and/or in the studio span David Gilmour, Roger Waters-less Pink Floyd, Roxy Music, Bryan Ferry, Madonna, Michael Jackson, Tom Jones, Iggy Pop, Icehouse (of which he was a band member), Kristy MacColl, Robert Palmer, Gary Moore, Debbie Harry, Johnny Marr, Robbie Robertson, Peter Cetera, Tears for Fears, David Coverdale- Jimmy Page, All Saints, The Orb, and Nick Mason’s Saucerful of Secrets, among others. Impressed, you should be!

If you’re a listener to Notes From An Artist and Rockonteurs – and you should be – you will immediately recognize the simpatico synergy between the two shows. David and I don’t have the piles of platinum discs that Guy and Gary have earned over the years, but we’ve been there and done that – the tours, sessions, the travel, the good deals, the mostly bad deals…

Hence our interview with Guy was not the typical linear podcast that one normally experiences with the obligatory introduction, tastefully imbedded product plug and follow-up, anecdotes, and farewell until we meet again.

Nope. Not even close. From the get-go, our discussion was enjoyably out of control. Akin to caged animals let free in the wilderness, the three of us came out chomping at the bit – with unbridled enthusiasm, one-upmanship, blotto bravado, and many joyful verbal collisions (“taking the piss” if you will).

Much like the popular Jerry Seinfeld TV series Comedians In Cars Getting Coffee – note that Guy also performs stand-up (or sit-down) comedy – we were chuffed to talk shop and then some sans the usual (and necessary) constraints of the radio/podcast format.

You have been warned. Here are excerpts from our free for all!

NFAA TOM: Let me introduce our audience member to Guy …

Pratt abruptly interrupts the prolog when he spots David’s custom Ken Bebensee six-string bass replete with a pinkish hue complimented by neon pink DR strings behind Gross at the onset of our Zoom chat.

GP: Whoa, what is that? It looks like some sort of psychedelic Ampeg bass!

NFAA DAVID: No! This is my six-string bass designed by a guy named Ken Bebensee with obligatory pink strings. You know, it takes a tough man to wear pink!

NFAA TOM: Non-binary strings?

GP: I don’t know that it does! Pink was a big 1950s color. Black and pink in particular. It was a big punk thing too. The Clash wore black and pink. Elvis wore black and pink.

NFAA TOM: Good observation Guy.

NFAA DAVID: The strings are great on stage because they glow under the lights which is very cool…

NFAA TOM: …much like the bass player.

GP: Tom..that’s a bass behind you as well (Pratt eyes Tom’s 1981 Steinberger XL – placed strategically to compliment David’s instrument)

NFAA TOM: Yes I set this out for our Johnny Marr interview …I know he’s a big fan of Steinberger instruments.

NFAA DAVID: It used to have a headstock…

GP: Johnny is definitely not a fan of those basses..

NFAA TOM: Yes I knew that factoid from reading your book My Bass and Other Animals. I’m using irony here…

GP: That’s why I bought ‘Betsy’ (“Betsy” is Guy’s nom de plume for his 1964 Fender Jazz Bass once owned by John Entwistle. Pratt purchased this instrument at the behest of The Smiths guitarist whose penchant for traditional instruments is well known. Marr felt the modish graphite Steinberger – which Pratt preferred – was not suitable for his post-Smiths aesthetic.)

NFAA TOM: You started Rockonteurs podcast with Gary Kemp during Covid lockdown, circa 2020, yes?

GP: This is the funny thing, we started it before Covid. The idea came to us being on the tour bus with the Saucers (Nick Mason’s Saucerful of Secrets band). I needed to while away the hours on our first European tour. In those days the buses still had DVD players. I brought along a box set of The Old Grey Whistle Test (a popular British television show which aired from 1971 -2018 featuring performances and interviews of music artists hosted by Bob Harris).

With Nick, I watched hours of 1970s rock TV. And Nick would be sharing all sorts of great personal stories about the people who were on the show. I had the idea of doing a show asking the people who were there – the artists. Before we could broadcast it we figured we’d get ten episodes together.

Gary and I went through our address books and we managed to get ten mates who agreed to be on the show. Back then, you had to go to a studio in London, you had to have a whole set up and everything like that. But then lockdown happened and suddenly the world went Zoom! You could have shit audio, and most important is that you could speak to anyone anywhere at any time. So we started before, but it was the lockdown that made us. How long have you guys been going?

NFAA TOM: David and I started off as The Bass Guitar Channel during lockdown three years ago (2020), and then we thought why the hell are we just talking to bass players?

NFAA DAVID: Boring old farts!

GP: Right!

NFAA TOM: We were mutual fans of each other’s websites – David has the Bass Guitar Channel, and I host the website and video series Know Your Bass Player. Of course, even under the banner of Notes From An Artist – we do favor bassists. Our guests include Bill Wyman who has been on the show twice, we’ve had Ron Carter on a few times. Rudy Sarzo (Ozzy Osbourne, Whitesnake, Quite Riot), Gerry McAvoy from Rory Gallagher, Benny Rietveld from Santana and Miles Davis, Jim Fielder from Blood Sweat & Tears, Harvey Brooks (Bob Dylan, Miles Davis)…

We’ve actually shared quite a few guests with Rockonteurs – Richard Thompson, Ian Anderson (Jethro Tull), Colin Blunstone (The Zombies), Steve Hackett (Genesis). David and I consider ourselves the American Rockonteurs – or Mockonteurs!

NFAA DAVID: You’ve played with Johnny Marr, David Coverdale, Nick Mason…

NFAA TOM: Many times, when David and I listen to podcasts hosted by non-musicians, we feel this angst, frustration, and even homicidal rage because the interviewers haven’t lived the life of a musician…I feel that we do which are peer-to-peer interviews, are very special.

NFAA DAVID: It’s very niche, but it can appeal to a broader audience.

GP: Yeah, yeah, yeah! It all depends on how you do it. Gary and I love to geek out. But this is the thing that I learned from years of doing my stand-up show, and that is you can’t appeal to just bass players. Half the guys have brought their missus. And they don’t want to be there. So you’ve got to do it in a way that makes sense for people who don’t really know or even care.

NFAA DAVID: One thing we learned very early on – it was the first time we had Ron Carter as a guest – we did not bring up Miles Davis. And you can understand that. He’s going strong in his 80s and five years of his life were with Miles. He’s done so many other things besides Miles…

GP: That’s hip, that’s cool! That’s seventy-five years’ worth!

NFAA DAVID: …so forty minutes into the interview… in his head, he must be going ‘no Miles? No Miles?’ We ended up getting Miles stories that no one had gotten before. Same thing with Bill Wyman. We didn’t mention the Rolling Stones once!

NFAA TOM: We read in your book how you made your bones as a bass player. Bernard Edwards noted, “That kid has a vibe!” Robert Palmer called you “the kid with the riffs!”

GP: Make that the kid with the ‘riff’ I just had one riff!

NFAA TOM: We’ve had some of your peers on the show such as bassists Lee Sklar (James Taylor, Jackson Brown, “The Section”), and Rudy Sarzo, and they never intended to be studio musicians – they preferred being in bands. What about you?

GP: It wasn’t really a proper profession. You got into rock and roll and you were in a band. It didn’t really exist. There were names you saw on Steely Dan records as part of some sort of unattainable Olympus. I wanted to play with people whose music I loved. And if I could help them make music, that would be even better.

I think I had it too easy for too long. Then I got to the wrong side of thirty and thought ‘What’s my manifesto?’ I’ve gone on and ticked off other boxes.

For me, the bass is like this poor dutiful loyal kind of wife, while I go off and have my affairs and run about town and then always come crawling back to her…

NFAA: Guy, you came to prominence in the 1980s – the decade dominated by electric bass!

GP: It was the best decade to be a bass player! Absolutely! In the world I was in – which was the current cool music of its time – everything from Bryan Ferry to Scritti Politti or whatever in British music – it was no longer about guitar. Guitar was small. Guitar played polite minor 7th chords – unless you were Johnny Marr. In fact – guitar was Johnny Marr!

It wasn’t David Gilmour or Jimmy Page. It was all about slapping. And also the bass seemed to be really responding well to technology. With instruments such as the Steinberger…

NFAA TOM: Your contemporaries were Pino Palladino, Paul Denman from Sadem, Norman Watt-Roy, Darryl Jones…Neil Jason

GP: Don’t forget Tony Levin!

NFAA TOM: Yes, you shared many a gig with Levin.

NFAA TOM: Talk about the influence of Mark King of Level 42 with his slap style on British players.

GP: Oh God yeah, he was a hero. There is footage on YouTube of my first production rehearsals with Pink Floyd when I first started playing with them in 1987. I have no idea how someone could sneak around with a camera back then – they were so huge. We were in a 747 airplane maintenance hanger at Toronto Airport – and you can hear Gary Wallace and me playing ‘Love Games.’ That’s what we did.

NFAA TOM: And you had to hold the bass high on the body – like a bow tie!

GP: Holding the bass that was a ‘New Romantic’ thing – which was done just to be as un-rock and roll as you could be. Literally holding the instrument under your chin…

When I look at that first Floyd tour – my bass is positioned a little higher than it is now.

NFAA TOM: Ergonomically – playing the bass too high is a problem – because you could tip over! Plus it’s a strain on your shoulders and upper arm. As we age, we develop pot bellies, so we need to lower the bass.

GP: It was quite funny with David (Gilmour) because he is much more svelte now… I would sneak to have a go on David’s guitar – I’d put it on and it would be down to my knees!

NFAA DAVID: On the topic of bass positioning – what I learned Billy Sheehan was to sit down with your instrument in your lap– get comfortable, then stand up and take a simple piece of leather and measure – and that’s your position!

GP: Brilliant! That’s way too grown-up and sensible!

NFAA DAVID: I could never understand Dee Dee Ramone playing with his bass near his ankles!

GP: But it looked fantastic! At the end of the day, are we musicians, or are we playing rock and roll?

NFAA TOM: There is actually an ergonomic reason why he did that. When you position your bass in the middle of your body – as most players do – you are using your forearm muscles. To play rapid eighth or sixteenth notes you need to use your wrist. Hence if you position the bass low beneath the hip – you work your wrist muscles.

GP: You’re absolutely right! Remember when the Boss Chorus came along and made everyone think they could play fretless? I am absolutely guilty of that! (Makes the sound of a chorus pedal) Rrrrrrrrr. Rrrrrrrr. Rrrrrr. Is that an E or an F? Who knows there’s a lot of chorus on it!

NFAA DAVID: It does not matter!

David C. Gross shows off his modified Tony Franklin fretless Fender bass aptly dubbed “The Franklin – Stein.” Gross had the instrument finished distressed, swapped out the Fender pick-ups for Lindy Fralin P-J configuration pups, and also replaced the Tony Franklin signature back plate. David notes that he shuts down the J bridge pick-up when playing the instrument. Gross notes that since he posted this bass on social media, Tony Franklin – a constant presence on Instagram and Facebook – has not spoken to him!

GP: I’m personally baffled by Precision fretless basses. To me, the Jazz seems to be the obvious fretless model because it needs a ‘bite’ with a pickup near the bridge. The person who would disagree with me is David Gilmour – who is a very fine fretless player. I think he used a Charvel fretless on ‘Hey You’ (Pink Floyd The Wall 1979).

NFAA DAVID: With me, it’s more comparable to my six-string as I prefer a big neck. Particularly a P neck with a C shape is the right one for me. Tony certainly got the neck right!

GP: For the Saucerful tours I play basses I’m not familiar with! The one thing I do with that band is try to be authentic. There’s no point in trying to copy those parts – in a lot of instances you can’t even hear them since they were mixed low on the original records most of the time. From ’67 to ’70 Roger played a Rickenbacker then in ’70 he switched to the Fender Precision. So I play Rickenbackers and Precisions which are not my first choice.

With the Precision I know it’s not the instrument – it’s me! Precisions are fabulous but it’s like certain Italian knitwear – I love it on other people!

As for the Rickenbacker – I just can’t really play it. But they make me play great for this gig because I kind of need to have one hand tied behind my back. And I have to play with a pick – so there’s no danger of me getting funky anywhere!

NFAA DAVID: I remember when Magical Mystery Tour (The Beatles, 1967) first came out. Those photos of Paul with a Rickenbacker looked great!

GP: Yes, it is a fantastic-looking instrument… but I never understood why it became a ‘prog rock’ bass with Chris Squire. Because it’s not a hi-fi-sounding instrument.

Getting back to Precisions – I think it all comes down to ‘What was the first bass you picked up!’ The first bass I played was a jazz-style instrument…

Pratt proceeds to jump out of his skin and show off the instrument that began his life’s journey ‘My dad gave it to me …it’s a Grant Japanese model– it was sunburst – I can never figure out why the black color followed the contour of the neck – then when I shaved it down I discovered it was plywood!’

GP: It’s that jazz profile which is all I’ve ever wanted… Then when I got Betsy – that his the most perfect profile neck I’ve ever come across.

NFAA TOM: And that’s the profile on your signature Betsy Bass available at The Bass Centre

Pratt hoists a Bass Center Betsy in his favorite hue – burgundy mist.