Latest

The Evolution of Bass Ramps

GWB35BKF Finger Ramp

There’s no doubt that for the last eight decades the Electric Bass Guitar has been the musical instrument with the most rapid evolution. It has evolved in many ways including, musically, functionally and technologically.

Within those technological aspects, over the last 27 years we’ve seen the appearance and evolution of a very simple device for the electric bass, the bass ramp. We’ve analyzed that evolution and made an attempt to establish just how it happened and who have been the players responsible for bringing this to the forefront.

The ‘Bass Ramp’, in general terms is a flat surface generally made out of wood that goes below the strings, which prevents the right hand fingers (left hand fingers for those playing left handed) from digging in too hard, providing the player a similar sensation to the feel they get when they play over the bass pickups, but spread over a much larger surface.

We have interviewed the five main bassists responsible for the evolution, who happen to be some of the finest bass players in the world. Included are Gary Grainger, Gary Willis, Igor Saavedra, Matt Garrison and Damian Erskine. Their invaluable collaboration with BMM allowed us to get all the information we needed to really dig deep and offer a serious analysis on this simple device.

After putting all the puzzle pieces in order, it seemed very clear to us that two bass ramp styles made a real difference, becoming the most recognizable and differentiated ramps that we now see everywhere, and are being installed in more basses every year. Depending on the different types, some of these ramps have slightly different names, mostly defined by their creators.

These two different bass ramps evolved sequentially and were created out of necessity by the five players. With all the information collected, we could also establish that the origin of a bass ramp was the bass pickups themselves, which gave the players that special ‘comfort feeling’; later they tried to replicate this feeling in a more specialized and dedicated way.

These are the two main bass ramp types that changed bass history, as well as the inventors behind them…

The Glued Ramp Located Beside or In Between the Pickups

This is the Genesis of the bass ramp and the title says it all. It’s a piece of wood that matches the shape of the pickups, that can either go between the neck and the neck pickup, between the neck pickup and the bridge pickup, between the bridge pickup and the bridge, or all of the options just mentioned at the same time. It generally goes attached with double-sided tape or just glued on.

We could establish that probably the first player to follow this path was Gary Willis. He started by putting together two bridge pickups in 1981 and then decided to find a bass with separated pickups and install a piece of wood in between them, probably around the beginning of 1986. We noticed that in videos prior to 1985, Willis appears playing with a Fender shaped bass with no ramp on it yet. We found a video of him playing with the Wayne Shorter Quartet on Sunday, July 13, 1996 at the North Sea Jazz Festival, where he’s playing a Tobias Bass loaded with what we think should be the very first bass ramp to be seen live; this famous ramp is known now by any dedicated bass player as, “The Willis Ramp”.

On the same path and probably coming with the same idea, without necessarily having seen Gary Willis ramp (as video was not as prominent as it is today), we assume that Gary Grainger started to use the same piece of wood in between two Soapbar Pickups around the second half of 1986 or beginning of 1987, based on the information he shared with us. We found a video of him playing live with the John Scofield Quartet in July 1986 at the Umbria Jazz Festival, where he can still be seen playing with his famous Musicman, where no ramp is attached. The first video recording that we could find where he can be seen using a bass ramp, loading his 5-string Ken Smith, was on a 1992 DCI Dennis Chambers instructional video, but as we mentioned before, he told us that he started to experiment with his first bass ramps around 1986 – 1987.

Finally, we include Matthew Garrison on this path, a highly distinguished and dedicated bass ramp user, who was the first to bring the concept to Fodera. Matt told us that he started to use this type of ramp right after trying the Gary Willis Signature Bass, loaded with the Willis Ramp at the 1994 NAMM Show.

The Adjustable Height Ramp That Contains the Pickups

Like any invention in the history of humanity it was clear that the first ramps had a lot of space to evolve. Also, in this case the title says it all; a ramp that has screws on the four corners, so as to adjust the height and at the same time contain the pickups inside so the player can play beside or over them if he wants, still keeping the same ramp feel.

South American Bassist Igor Saavedra came up with an idea almost 20 years ago, an adjustable height bass ramp that contained the pickups, instead of being placed on their sides, glued to the body of the bass. He came up with the idea after having a conversation with Gary Willis in Chile back in 1992. Igor shared, “The first prototypes were done by himself back in 1995, but the first official ‘MicRamp’, was commissioned by Luthier Alfonso Iturra in late 1998 and finished in 1999, loading a 6-string bass that he was handcrafting for me.” Igor can be seen everywhere playing with his MicRamp in many videos and footage from 1999 and up.

Happening during the same timeframe in the United States, Damian Erskine developed a very similar bass ramp, which he called the, “Rampbar” and was made for him by the great Luthier, Pete Skjold around 2010.

All of the above was extracted from the actual interviews that we did with these five well-known bassists and we have now the pleasure to leave you with the actual interviews, so you can get the story first hand. We hope you enjoy their stories as much as we did.

1) What was the exact year you did your first ramp and the reasons that lead you to do it?

It was somewhere around 1981 and it wasn’t actually a ramp yet. I had these DiMarzio pickups and I put two of them side-by-side in the rear pickup position. They had threaded pole pieces that you could raise or lower so when I raised the middle ones the sharp threads were cutting my fingers. So I got a hole-puncher and added layers of tape to protect my fingers and also was able to shape the surface so that it had equal string to pickup spacing. So it had kind of a contour – a ramp – if you will. The contour gave it a very consistent feel for my three finger technique.

I wasn’t thrilled with the side-by-side pickup sound so on my next bass I attached a contoured piece of wood next to the pickup so I could have that same sensation of a consistent playing surface under my three fingers.

2) Inventions in history are always based on a previous invention, where did your idea came from?

You can sort of tell that it wasn’t based on anything previous, I was just originally trying to prevent losing skin!

3) With your first ramp… did you do it yourself or ask a Luthier?

I always did them myself and I’ve probably made over 200 for people throughout the years. When I finally started having companies build basses for me then it became part of the design.

4) Have you made any improvements to it throughout the years?

When Ibanez released the first version back in 1999, we weren’t sure about the ramp’s acceptance so we made it removable. It was attached with double sided tape so it was adjustable but if someone didn’t want it, it could be removed. As time passed and ramps became more accepted, we put screws to make it adjustable.

5) What are the technical benefits you got from your ramp, did it change the way you play?

The technical benefits are numerous. First, it eliminates digging in too hard and hearing that ugly sound of the string banging against the fingerboard. Second, it allows you to get warmer tones from playing further away from the bridge while still giving that consistent feel. Third, of course, is that it makes the perfect thumb rest. Fourth, since it reinforces the concept of playing lighter (you compensate by turning up) it will allow more fundamental and air throughout the duration of a note, instead of thinning out right away after the attack from playing too hard. Finally, if used and set up properly, it will allow you to discover a broader range of dynamics while getting a better tone.

The first version just gave a sense of security to my three fingers, since that was all it would accommodate. But as I gradually extended it, eventually eliminating the front pickup and reaching all the way to the neck, I discovered how the benefits of playing closer to the neck for certain tones. So yes, if a ramp is adjusted properly it should change the way you play.

6) Have you any legal patents on your invention?

It’s not patented. And it doesn’t make sense to patent it unless I wanted to become a patent troll and just punish people for using it. It wouldn’t make a profit since you can’t really define its dimensions because of all the different pickup configurations out there. Plus before it’s installed, the pickup height and action has to be set. So it kind of has to be fabricated bass-by-bass.

7) What are your thoughts when you see your ramp being used by so many bassists nowadays?

It’s great to see. I can’t take exclusive credit for inventing it since I’ve heard of other people developing it independent of me, but I’m glad to see players developing an awareness of dynamics and touch and using the ramp to help with that.

Visit online at garywillis.com

1) What was the exact year you did your first ramp and the reasons that lead you to do it?

It was around the same time I started playing with John Scofield… so that would be about 1986, 87.

2) Inventions in history are always based on a previous invention, where did your idea came from?

The first bass I had and learned how to play was a Fender Precision with a Humbucking pick-up on it. Later, I bought a Music Man Sting Ray, which also had the big pick-up on it.

When I picked up other bases, I did not like how it felt when I played finger style….then….I realized that I was using the big Humbucking pick-up on the basses as a way of stopping my fingers from going too far down in the strings when I played. So, I had a piece of wood placed where I like to play with my fingers on my other basses and that made it feel right to me.

At that point, I bought a Ken Smith five and I had the block of wood glued to the bass. It felt great. Then, I started working with Paul Reed Smith on building a bass for me. The bass turned out to be amazing, so now I have a signature bass line with PRS and we offer the 4 and 5 string basses with or with-out the ramp.

3) With your first ramp… did you do it yourself or ask a Luthier?

I had “John Warden” (Guitar & Bass builder and repair man) cut and place the ramps on for me at that time. Now PRS does it for my basses.

4) Have you made any improvements to it throughout the years?

The only improvement that I made was to have little trenches dug out on the ramps to allow the strings to vibrate on my basses.

5) What are the technical benefits you got from your ramp, did it change the way you play?

It allows me to play with a lighter touch which I think helps me avoid some hand tension problems that comes sometimes when we play.

6) Have you any legal patents on your invention?

No, I have no patents on the ramp.

7) What are your thoughts when you see your ramp being used by so many bassists nowadays?

I think it is great to see so many players that think the same way that I do……cool.

Find online: prsguitars.com/artists/profile/gary_grainger

1) What was the exact year you did your first ramp and the reasons that lead you to do it?

I was lucky to meet Gary Willis on his visit to Chile with Tribal Tech back in 1992. I lent him my amplifier for the concert, and that allowed me to be in the theater for the sound check. I was intrigued by that piece of wood his bass had, so I asked him everything I could about it. He was very kind to explain to me all of the details and the benefits, and when I grabbed the bass I just loved the sensation. I almost immediately asked him if it could be height adjustable and if there were pickups underneath the ramp. He told me that it wasn’t height adjustable and that there were not any pickups underneath, adding that he was quite comfortable with the way his ramp was but encouraged me to investigate more if I felt it necessary. In fact I felt it very necessary and kept thinking about that idea until 1995 when I did my first prototype and a few more between 1995 and 1998. My first official MicRamp, which was the name I gave it, was inserted as a structural component of a 6-string bass that I commissioned to do with the well-known Luthier and former sponsor Alfonso Iturra. He started to build that in late 1998 and finished it in 1999.

2) Inventions in history are always based on a previous invention, where did your idea came from?

There’s no doubt about it for me… my MicRamp is a direct descendant of the Willis Ramp. It exists because of it and also because of Gary Willis’ encouragement to go for it. I thank him for being so kind with me back in those years when I was just starting to play bass, because I’m pretty sure I must have overwhelmed him with so many questions that day.

3) With your first ramp… did you do it yourself or ask a Luthier?

The first ones I did them myself, and eventually commissioned Alfonso Iturra, as a master Luthier, I knew the ramp was going to be really well made, which it was.

4) Have you made any improvements to it throughout the years?

Oh sure… there were 3 prototype versions between 1995 and 1998, then two more versions made by Alfonso Iturra for a 6-string and my first 8-string bass Octavius 1.0. The 6.0 Version was made by the great Chilean Luthier Claudio González, loading my Octavius 2.0, which is my most famous bass untill now. My actual official ramp was made by Oscar Prat loading my new PRAT Signature Bass and is the 7.0 version, which in fact is absolutely outstanding. It is good to point out that one of the characteristics that define the MicRamp is that the screws (Allen) are inserted from behind the bass body, and always have, so they are not noticeable from the front. Also the MicRamp has always been loaded with springs around those screws, for keeping the height stable.

5) What are the technical benefits you got from your ramp, did it change the way you play?

There are plenty. First of all the height adjustment allows you to follow any change you want to make on the bass (action) or in your playing (grip & touch), so being in that comfort zone, your playing will be as soft as you want it to be. Also the grip on the strings will be super-steady with the inherent dynamics and stability benefits, along with a relaxed hand position to rest over the ramp that will be able to achieve much more cleanness and speed if needed. Second, having the pickups inserted on the ramp allows you to play right over where the sound is being captured, and due to the fact that the MicRamp is larger than the pickups you can also play in between and on the sides of the pickups if you want. Third, having an absolutely flat surface with no screws coming from the front brings you a lot of “Peace of Mind,” so no matter where you are playing you will never scratch your fingertips with the head of a screw or the edge of their hole. Fourth, sound is not affected at all. Fifth, it just looks so beautiful without the screws in the front.

6) Have you any legal patents on your invention?

No, and do not have any intention. My idea belongs now to the world’s bass community and I don’t even imagine myself wasting my time in lawyers and crazy paperwork for something like that. I know I was the first to come up with the idea and that’s enough for me and the bass community supports that fact. I’m aware that many years later there have been a couple of great bassists that came to the same conclusion without necessarily knowing about my MicRamp and that’s absolutely fair.

7) What are your thoughts when you see your ramp being used by so many bassists nowadays?

It feels really great… it’s a sensation of giving and sharing something that has come out of your life and your experiences, something very similar to when I teach, but just applied on a different context. Each time I see a bass loaded with a MicRamp I feel that a little piece of me is living on it… the screws of those ramps are usually inserted from the front though, so if you want to go the “Original Style” ask your Luthier to insert them from the rear, it just looks much better IMHO (smile).

Visit online at bajoigorsaavedra.cl

1) What was the exact year you did your first ramp and the reasons that lead you to do it?

1994. I had played Gary Willis’s signature bass during that years NAMM and knew immediately it would help me develop the four-finger technique I was just developing at the time. Everything just fell into place after I had Fodera install the ramp on my signature model. They were a little puzzled at the request since no one had ever asked for a ramp to be installed on one of their basses, but shortly thereafter it all made sense to all of us.

2) Inventions in history are always based on a previous invention, where did your idea came from?

I didn’t invent anything in this department. Apparently Gary Grainger had a ramp installed on his bass prior to Gary Willis as Grainger points out, so perhaps he’s the very first bass player to have navigated this new territory. He would be a great artist to talk to regarding this topic. However I only encountered the use of a ramp for the first time on Gary Willis’s bass.

3) With your first ramp… did you do it yourself or ask a Luthier?

I asked the gang at Fodera.

4) Have you made any improvements to it throughout the years?

Sure. We tried different woods, different positioning, different options in terms of being able to take it off if necessary. Also we tried different ways of adjusting the individual levels of the four corners of the ramp.

5) What are the technical benefits you got from your ramp, did it change the way you play?

Absolutely changed my playing forever. I could all of the sudden accomplish certain technical ideas that were just too tricky without the ramp. I’m still finding new uses for the ramp. The only downside is of course to really do what I do technically I can only do it with a ramp installed. Of course I can take care of my bass playing basics without, however my language is fully built around the use of a ramp.

6) What are your thoughts when you see ramps being used by so many bassists nowadays?

I think it’s magnificent how such a simple piece of technology makes sense to so many bass players around the world. It’s not just a series of people imitating an action for the sake of imitation. There are true benefits to the concept and it’s amazing how wide spread it is. We must all give thanks to Gary Grainger and Gary Willis as the true innovators regarding this idea.

Visit online at garrisonjazz.com

1) What was the year you did your first ramp and the reasons that lead you to do it?

I believe that I installed my first ramp on my Modulus 6 string back in 1999 or so. I was always one to play over the pickups and I was intrigued by the idea of broadening my ‘comfort zone’ in between the bridge and the neck. My current ramp style was developed in conjunction with Pete Skjold somewhere around 2010 or 2011. The ramp I have on my Skjold basses is a hybrid. We’ve combined the pickup moulds with the ramp so we have, essentially, two soap-bar pickups incorporated into an oversized pickup mould (which matches the contour of the fretboard perfectly).

2) Inventions in history are always based on a previous invention, where did your idea came from?

Although I can’t remember where I first saw or heard of the idea for any kind of ramp, it was likely by checking out Gary Willis. I was always one to tinker with everything though. I had an obsessive need to personalize my gear (not visually, but functionally). I loved evaluating HOW I played and then trying to make the instrument better assist me in any way.

3) With your first ramp… did you do it yourself or ask a Luthier?

When building my first wooden ramps, I actually just scoured the waste pile of a furniture maker until I found something that looked nice and was something close to the right size. I then made some cuts, sanded it down and used double sided tape to attach it. I was lucky in as much as the Modulus had both flat pickups and a flat fingerboard, so I didn’t have to worry about radiusing the ramp at all. I had to have a Luthier install some later ramps on basses that had radiused finger boards. I also had to start making sure that I always had pickups that matched the radius of my neck. It drove me crazy for about a year when I had a bass with a radiused board, radiused ramp and flat pickups! Had to get those switched out… kicked my ocd into hyper drive! Lol

Now, my Skjold ramps can only be made by Pete Skjold. Also, the pickups are custom wound so he’s really the guy who does most everything (beyond basic setup and tweaking) on my basses.

4) Have you made any improvements to it throughout the years?

Well, by now Pete Skjold and I have come up with our own pickup moulds that incorporate the ramp. Most people assume that it is just a cover but the pickups are wired directly into that large mold creating one smooth giant looking pickup that serves as the ramp. We explored this because we wanted one smooth surface with no edges but weren’t so much into the idea of just plopping a cover over the pickups. I couldn’t be happier with the results!

5) What are the technical benefits you got from your ramp, did it change the way you play?

Initially I liked ramps because they kept me from digging in too hard. It forced me to play a little lighter as well as evening out my right hand technique. Now, I actually set the pickup/ramp a bit lower than I used to because I like to have more dynamic range available to me with my right hand, but it still feels like home. I like feeling something under my fingers when I play. I have also been using my thumb (not slapping, though… just finger style) quite a bit over the past few years and the ramp has really helped me to maintain control over my strikes, keeping them even across my 3 plucking fingers.

6) Have you any legal patents on your invention?

No, although Pete Skjold may have some on certain aspects of his design (not really sure, though!).

7) What are your thoughts when you see ramps being used by so many bassists nowadays?

I’m all for innovation. It helps to facilitate a certain style of playing. I always hope that all players explore the instrument fully and decide what their voice and preferred tactile experience really is on the instrument before they just do what X or Y player is doing. Everything I’ve tweaked on my basses (chambering, my Duo-Strap with Gruv Gear, ramp style pickup) has come about through the exploration of my style and my voice. I think it’s important to fully explore your instrument, your musical voice and then work to bring the two together in harmony.

Visit online at damianerskine.com

Gear

New Joe Dart Bass From Sterling By Music Man

Sterling by Music Man introduces the Joe Dart Artist Series Bass (“Joe Dart”), named after and designed in collaboration with the celebrated Vulfpeck bassist.

Above photo credit: JORDAN THIBEAUX

This highly-anticipated model marks the debut of the Dart bass in the Sterling by Music Man lineup, paying homage to the Ernie Ball Music Man original that all funk players know and love. The bass embodies many of the original model’s distinctive features, from its iconic minimalist design to the passive electronics.

The design process prioritized reliability, playability, and accessibility at the forefront. Constructed from the timeless Sterling body, the Dart features a slightly smaller neck profile, offering a clean tone within a comfortable package. The body is crafted from soft maple wood for clarity and warmth while the natural finish emphasizes the simple yet unique look.

Engineered for straightforward performance, this passive bass features a ceramic humbucking bridge pickup and a single ‘toaster’ knob for volume control. Reliable with a classic tone, it’s perfect for playing in the pocket. The Dart is strung with the all-new Ernie Ball Stainless Steel Flatwound Electric Bass Strings for the smoothest feel and a mellow sound.

The Sterling by Music Man Joe Dart Bass is a special “Timed Edition” release, exclusively available for order on the Sterling by Music Man website for just one month. Each bass is made to order, with the window closing on May 31st and shipping starting in November. A dedicated countdown timer will indicate the remaining time for purchase on the product page. Additionally, the back of the headstock will be marked with a “2024 Crop” stamp to commemorate the harvest year for this special, one-of-a-kind release.

The Joe Dart Bass is priced at $399.99 (MAP) and can be ordered globally at https://sterlingbymusicman.com/products/joe-dart.

To learn more about Joe Dart, visit the official Vulfpeck artist site here https://www.vulfpeck.com/.

Cover

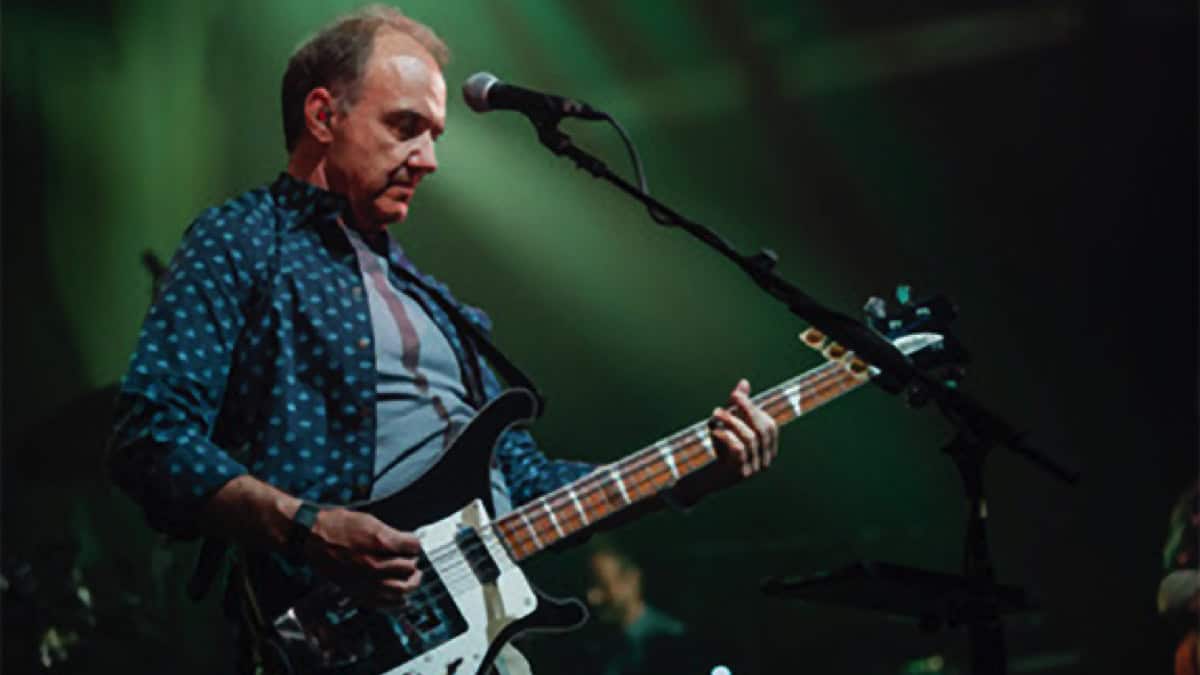

Guy Pratt, Not Your Average Guy – May 2024 Issue

Guy Pratt, Not Your Average Guy – May 2024 Issue

For me, the bass is like this poor dutiful, loyal kind of wife. I go off and have my affairs and run about town, then I always come crawling back to her… Guy Pratt

By David C. Gross and Tom Semioli

Photo Courtesy – Cover Photo, Paul Mac Manus | Promo, Tarquin Gotch

Most rock and pop devotees know the individual names, likenesses, and other “intimate” details of their beloved ensembles.

Everyone has/had their favorite Beatle… darling Rolling Stone… preferred Led Zeppelin, their chosen who’s in the Who – etcetera.

And even in those instances, the enigmatic lead singer and swaggering lead guitarist garner the most consideration in the public eye. Aspiring drummers, keyboardists, and bassists will naturally gravitate to their said instrumentalists. Civilians could care less.

In the case of the singular artist, it’s all about the headliner, and quite frankly, that’s just how the nature of rock celebrity works. It’s the name on the ticket that counts.

On rare occasions, the second banana gets peeled: Mick Ronson spidering beside David Bowie, Steve Stevens rebel yelling in the service of Billy Idol, Scotty Moore twangin’ with Elvis Presley, and Steve Vai shredding alongside David Lee Roth, to cite a select small number. “Very few are chosen and even fewer still are called…” to quote Warren Zevon who piled his craft with guitarist Waddy Wachtel in tow.

Rarer still are the sideman/session bass players who somehow catch the slightest edge of any spotlight. Motown legend James Jamerson Jr. was not recognized until long after his passing by way of the 2002 Paul Justman documentary Standing In The Shadows of Motown which was a surprising box-office success and consequently spurred on similar films such as The Wrecking Crew (2008) Muscle Shoals (2013). Even then, these studio cats’ time in the sunset as soon as the film credits rolled.

Other bassists in the strictly accompaniment arena catch a notable wave by the nature of their unique contributions to international hit songs – witness Pino Palladino with Paul Young (“Every Time You Go Away”). Studio ace Will Lee (for whom David C. Gross oft subbed), gesticulating in proximity to charismatic bandleader Paul Shaffer, was visible to millions in his four decades with Late Night with David Letterman, and The Late Show with David Letterman. Rarified air indeed.

Which brings us to Guy Allen Pratt. Born in 1962 in a place called Lambeth London, Pratt came to the instrument in the funky 1970s when bass, thanks to improvements in audio and recording technology, could actually be heard on the radio and on hi-fi record players of the day. Rather than prattle on about Pratt’s formative years, we highly recommend his hysterical autobiography My Bass and Other Animals (2007) Orion books.

David and I love talking to our record collection on Notes From An Artist. Guy not only talks to his record recollection on his podcast Rockonteurs with co-host Gary Kemp of Spandau Ballet fame but he’s played with them! You (lovable) bastard!

Guy’s credits on stage and/or in the studio span David Gilmour, Roger Waters-less Pink Floyd, Roxy Music, Bryan Ferry, Madonna, Michael Jackson, Tom Jones, Iggy Pop, Icehouse (of which he was a band member), Kristy MacColl, Robert Palmer, Gary Moore, Debbie Harry, Johnny Marr, Robbie Robertson, Peter Cetera, Tears for Fears, David Coverdale- Jimmy Page, All Saints, The Orb, and Nick Mason’s Saucerful of Secrets, among others. Impressed, you should be!

If you’re a listener to Notes From An Artist and Rockonteurs – and you should be – you will immediately recognize the simpatico synergy between the two shows. David and I don’t have the piles of platinum discs that Guy and Gary have earned over the years, but we’ve been there and done that – the tours, sessions, the travel, the good deals, the mostly bad deals…

Hence our interview with Guy was not the typical linear podcast that one normally experiences with the obligatory introduction, tastefully imbedded product plug and follow-up, anecdotes, and farewell until we meet again.

Nope. Not even close. From the get-go, our discussion was enjoyably out of control. Akin to caged animals let free in the wilderness, the three of us came out chomping at the bit – with unbridled enthusiasm, one-upmanship, blotto bravado, and many joyful verbal collisions (“taking the piss” if you will).

Much like the popular Jerry Seinfeld TV series Comedians In Cars Getting Coffee – note that Guy also performs stand-up (or sit-down) comedy – we were chuffed to talk shop and then some sans the usual (and necessary) constraints of the radio/podcast format.

You have been warned. Here are excerpts from our free for all!

NFAA TOM: Let me introduce our audience member to Guy …

Pratt abruptly interrupts the prolog when he spots David’s custom Ken Bebensee six-string bass replete with a pinkish hue complimented by neon pink DR strings behind Gross at the onset of our Zoom chat.

GP: Whoa, what is that? It looks like some sort of psychedelic Ampeg bass!

NFAA DAVID: No! This is my six-string bass designed by a guy named Ken Bebensee with obligatory pink strings. You know, it takes a tough man to wear pink!

NFAA TOM: Non-binary strings?

GP: I don’t know that it does! Pink was a big 1950s color. Black and pink in particular. It was a big punk thing too. The Clash wore black and pink. Elvis wore black and pink.

NFAA TOM: Good observation Guy.

NFAA DAVID: The strings are great on stage because they glow under the lights which is very cool…

NFAA TOM: …much like the bass player.

GP: Tom..that’s a bass behind you as well (Pratt eyes Tom’s 1981 Steinberger XL – placed strategically to compliment David’s instrument)

NFAA TOM: Yes I set this out for our Johnny Marr interview …I know he’s a big fan of Steinberger instruments.

NFAA DAVID: It used to have a headstock…

GP: Johnny is definitely not a fan of those basses..

NFAA TOM: Yes I knew that factoid from reading your book My Bass and Other Animals. I’m using irony here…

GP: That’s why I bought ‘Betsy’ (“Betsy” is Guy’s nom de plume for his 1964 Fender Jazz Bass once owned by John Entwistle. Pratt purchased this instrument at the behest of The Smiths guitarist whose penchant for traditional instruments is well known. Marr felt the modish graphite Steinberger – which Pratt preferred – was not suitable for his post-Smiths aesthetic.)

NFAA TOM: You started Rockonteurs podcast with Gary Kemp during Covid lockdown, circa 2020, yes?

GP: This is the funny thing, we started it before Covid. The idea came to us being on the tour bus with the Saucers (Nick Mason’s Saucerful of Secrets band). I needed to while away the hours on our first European tour. In those days the buses still had DVD players. I brought along a box set of The Old Grey Whistle Test (a popular British television show which aired from 1971 -2018 featuring performances and interviews of music artists hosted by Bob Harris).

With Nick, I watched hours of 1970s rock TV. And Nick would be sharing all sorts of great personal stories about the people who were on the show. I had the idea of doing a show asking the people who were there – the artists. Before we could broadcast it we figured we’d get ten episodes together.

Gary and I went through our address books and we managed to get ten mates who agreed to be on the show. Back then, you had to go to a studio in London, you had to have a whole set up and everything like that. But then lockdown happened and suddenly the world went Zoom! You could have shit audio, and most important is that you could speak to anyone anywhere at any time. So we started before, but it was the lockdown that made us. How long have you guys been going?

NFAA TOM: David and I started off as The Bass Guitar Channel during lockdown three years ago (2020), and then we thought why the hell are we just talking to bass players?

NFAA DAVID: Boring old farts!

GP: Right!

NFAA TOM: We were mutual fans of each other’s websites – David has the Bass Guitar Channel, and I host the website and video series Know Your Bass Player. Of course, even under the banner of Notes From An Artist – we do favor bassists. Our guests include Bill Wyman who has been on the show twice, we’ve had Ron Carter on a few times. Rudy Sarzo (Ozzy Osbourne, Whitesnake, Quite Riot), Gerry McAvoy from Rory Gallagher, Benny Rietveld from Santana and Miles Davis, Jim Fielder from Blood Sweat & Tears, Harvey Brooks (Bob Dylan, Miles Davis)…

We’ve actually shared quite a few guests with Rockonteurs – Richard Thompson, Ian Anderson (Jethro Tull), Colin Blunstone (The Zombies), Steve Hackett (Genesis). David and I consider ourselves the American Rockonteurs – or Mockonteurs!

NFAA DAVID: You’ve played with Johnny Marr, David Coverdale, Nick Mason…

NFAA TOM: Many times, when David and I listen to podcasts hosted by non-musicians, we feel this angst, frustration, and even homicidal rage because the interviewers haven’t lived the life of a musician…I feel that we do which are peer-to-peer interviews, are very special.

NFAA DAVID: It’s very niche, but it can appeal to a broader audience.

GP: Yeah, yeah, yeah! It all depends on how you do it. Gary and I love to geek out. But this is the thing that I learned from years of doing my stand-up show, and that is you can’t appeal to just bass players. Half the guys have brought their missus. And they don’t want to be there. So you’ve got to do it in a way that makes sense for people who don’t really know or even care.

NFAA DAVID: One thing we learned very early on – it was the first time we had Ron Carter as a guest – we did not bring up Miles Davis. And you can understand that. He’s going strong in his 80s and five years of his life were with Miles. He’s done so many other things besides Miles…

GP: That’s hip, that’s cool! That’s seventy-five years’ worth!

NFAA DAVID: …so forty minutes into the interview… in his head, he must be going ‘no Miles? No Miles?’ We ended up getting Miles stories that no one had gotten before. Same thing with Bill Wyman. We didn’t mention the Rolling Stones once!

NFAA TOM: We read in your book how you made your bones as a bass player. Bernard Edwards noted, “That kid has a vibe!” Robert Palmer called you “the kid with the riffs!”

GP: Make that the kid with the ‘riff’ I just had one riff!

NFAA TOM: We’ve had some of your peers on the show such as bassists Lee Sklar (James Taylor, Jackson Brown, “The Section”), and Rudy Sarzo, and they never intended to be studio musicians – they preferred being in bands. What about you?

GP: It wasn’t really a proper profession. You got into rock and roll and you were in a band. It didn’t really exist. There were names you saw on Steely Dan records as part of some sort of unattainable Olympus. I wanted to play with people whose music I loved. And if I could help them make music, that would be even better.

I think I had it too easy for too long. Then I got to the wrong side of thirty and thought ‘What’s my manifesto?’ I’ve gone on and ticked off other boxes.

For me, the bass is like this poor dutiful loyal kind of wife, while I go off and have my affairs and run about town and then always come crawling back to her…

NFAA: Guy, you came to prominence in the 1980s – the decade dominated by electric bass!

GP: It was the best decade to be a bass player! Absolutely! In the world I was in – which was the current cool music of its time – everything from Bryan Ferry to Scritti Politti or whatever in British music – it was no longer about guitar. Guitar was small. Guitar played polite minor 7th chords – unless you were Johnny Marr. In fact – guitar was Johnny Marr!

It wasn’t David Gilmour or Jimmy Page. It was all about slapping. And also the bass seemed to be really responding well to technology. With instruments such as the Steinberger…

NFAA TOM: Your contemporaries were Pino Palladino, Paul Denman from Sadem, Norman Watt-Roy, Darryl Jones…Neil Jason

GP: Don’t forget Tony Levin!

NFAA TOM: Yes, you shared many a gig with Levin.

NFAA TOM: Talk about the influence of Mark King of Level 42 with his slap style on British players.

GP: Oh God yeah, he was a hero. There is footage on YouTube of my first production rehearsals with Pink Floyd when I first started playing with them in 1987. I have no idea how someone could sneak around with a camera back then – they were so huge. We were in a 747 airplane maintenance hanger at Toronto Airport – and you can hear Gary Wallace and me playing ‘Love Games.’ That’s what we did.

NFAA TOM: And you had to hold the bass high on the body – like a bow tie!

GP: Holding the bass that was a ‘New Romantic’ thing – which was done just to be as un-rock and roll as you could be. Literally holding the instrument under your chin…

When I look at that first Floyd tour – my bass is positioned a little higher than it is now.

NFAA TOM: Ergonomically – playing the bass too high is a problem – because you could tip over! Plus it’s a strain on your shoulders and upper arm. As we age, we develop pot bellies, so we need to lower the bass.

GP: It was quite funny with David (Gilmour) because he is much more svelte now… I would sneak to have a go on David’s guitar – I’d put it on and it would be down to my knees!

NFAA DAVID: On the topic of bass positioning – what I learned Billy Sheehan was to sit down with your instrument in your lap– get comfortable, then stand up and take a simple piece of leather and measure – and that’s your position!

GP: Brilliant! That’s way too grown-up and sensible!

NFAA DAVID: I could never understand Dee Dee Ramone playing with his bass near his ankles!

GP: But it looked fantastic! At the end of the day, are we musicians, or are we playing rock and roll?

NFAA TOM: There is actually an ergonomic reason why he did that. When you position your bass in the middle of your body – as most players do – you are using your forearm muscles. To play rapid eighth or sixteenth notes you need to use your wrist. Hence if you position the bass low beneath the hip – you work your wrist muscles.

GP: You’re absolutely right! Remember when the Boss Chorus came along and made everyone think they could play fretless? I am absolutely guilty of that! (Makes the sound of a chorus pedal) Rrrrrrrrr. Rrrrrrrr. Rrrrrr. Is that an E or an F? Who knows there’s a lot of chorus on it!

NFAA DAVID: It does not matter!

David C. Gross shows off his modified Tony Franklin fretless Fender bass aptly dubbed “The Franklin – Stein.” Gross had the instrument finished distressed, swapped out the Fender pick-ups for Lindy Fralin P-J configuration pups, and also replaced the Tony Franklin signature back plate. David notes that he shuts down the J bridge pick-up when playing the instrument. Gross notes that since he posted this bass on social media, Tony Franklin – a constant presence on Instagram and Facebook – has not spoken to him!

GP: I’m personally baffled by Precision fretless basses. To me, the Jazz seems to be the obvious fretless model because it needs a ‘bite’ with a pickup near the bridge. The person who would disagree with me is David Gilmour – who is a very fine fretless player. I think he used a Charvel fretless on ‘Hey You’ (Pink Floyd The Wall 1979).

NFAA DAVID: With me, it’s more comparable to my six-string as I prefer a big neck. Particularly a P neck with a C shape is the right one for me. Tony certainly got the neck right!

GP: For the Saucerful tours I play basses I’m not familiar with! The one thing I do with that band is try to be authentic. There’s no point in trying to copy those parts – in a lot of instances you can’t even hear them since they were mixed low on the original records most of the time. From ’67 to ’70 Roger played a Rickenbacker then in ’70 he switched to the Fender Precision. So I play Rickenbackers and Precisions which are not my first choice.

With the Precision I know it’s not the instrument – it’s me! Precisions are fabulous but it’s like certain Italian knitwear – I love it on other people!

As for the Rickenbacker – I just can’t really play it. But they make me play great for this gig because I kind of need to have one hand tied behind my back. And I have to play with a pick – so there’s no danger of me getting funky anywhere!

NFAA DAVID: I remember when Magical Mystery Tour (The Beatles, 1967) first came out. Those photos of Paul with a Rickenbacker looked great!

GP: Yes, it is a fantastic-looking instrument… but I never understood why it became a ‘prog rock’ bass with Chris Squire. Because it’s not a hi-fi-sounding instrument.

Getting back to Precisions – I think it all comes down to ‘What was the first bass you picked up!’ The first bass I played was a jazz-style instrument…

Pratt proceeds to jump out of his skin and show off the instrument that began his life’s journey ‘My dad gave it to me …it’s a Grant Japanese model– it was sunburst – I can never figure out why the black color followed the contour of the neck – then when I shaved it down I discovered it was plywood!’

GP: It’s that jazz profile which is all I’ve ever wanted… Then when I got Betsy – that his the most perfect profile neck I’ve ever come across.

NFAA TOM: And that’s the profile on your signature Betsy Bass available at The Bass Centre

Pratt hoists a Bass Center Betsy in his favorite hue – burgundy mist.

GP: It’s the best-selling bass they’ve ever had! I used this Bass Centre bass at a cancer charity gig the other week (November 2023) with Andy Taylor and Robert Plant. So how’s this for a ‘box tick’ – I’m one of the few people, apart from John Paul Jones to have played “Black Dog” with Jimmy Page, and Robert Plant!

NFAA TOM: The big I am! Let’s talk about Betsy – you added a Badass bridge…

GP: The Badass is an option… I use the cheap one! The secret to that bass is the EMG pickups. People don’t usually put EMG pickups into an old bass…it has the lovely, settled, resonant wood. Stick active EMGs into an old bass and…boom! It’s fantastic!

NFAA TOM: David, you can compliment the burgundy mist Betsy bass with your signature neon pink strings!

Pratt proudly displays the original Betsy bass guitar once owned by John Entwistle of The Who.

GP: Here’s the old girl!

NFAA TOM: Is that the “My Generation” bass?

GP: No, John never played this bass. Owning a bass that belonged to John Entwistle is like owning a pair of shoes that belonged to Imelda Marcos!

NFAA DAVID: John owned a very conceivable bass in several colors.

GP: The rumor I heard was that Fender made three full sets of Burgundy Mist guitars in 1964. And John owned the full set- a Precision, Jazz, Telecaster, Stratocaster, Jazz Master – he had everything. Which was priceless, but he had to sell them all in a hurry. So I purchased this bass through the legendary guitar tech Alan Rogan.

The conversation drifts on to the punk era which Pratt experienced as an impressionable teenager.

NFAA TOM: We didn’t get the Sex Pistols until late in their career and then of course, the band broke up in the USA following a show in Texas. That band must have had an impact on a young Guy Pratt.

GP: Oh totally! If you discovered rock and roll at that point like I did, it made an impact. But the stuff I loved were the bands that survived. I loved The Who – Pete stayed totally cool throughout punk – no one was going to touch Pete! Twelve years before punk, Pete was smashing guitars on stage. No one was ever going to do anything as punk rock as that!

I liked Bruce Springsteen who became great friends with Joe Strummer. There was this thing that there were five bands – they were these people who were rich and over thirty years old, which we couldn’t relate to as teenagers.

What was so brilliant about punk – and it’s the reason why the 1980s were so brilliant – was the ‘do it yourself’ aspect of punk. In England at the time the attitude was if you don’t like a band – start your own band. If you don’t like what is in the newspapers – start your own newspaper!

When The Buzzcocks heard about the Sex Pistols they booked them to play at the Lesser Free Trade Hall in Manchester. They played and there were about fourteen people at the show. And those fourteen people were Morrissey, Johnny Marr, Mick Hucknell, Tony Wilson, Steven Morris, Ian Curtis…basically the 1980s!

NFAA DAVID: I’m surprised that The Damned never broke in this country. They were another “fake” punk band that was brilliant.

GP: I know what you mean. They were like The Monkees of punk. And I say that as someone who adored The Monkees when I was a kid.

NFAA TOM: Talking about your history of session work… when we are in the studio oft times we are required to either read a lead sheet or a written out note-for-note chart. According to your book, Madonna asked up to create a bassline that made your (anatomy deleted) hard!

GP: She was terrifying!

NFAA TOM: In your book, you detail how you forgot that you played the iconic bassline to “Like A Prayer” which bolstered your career.

GP: Right! I had a vague recollection of that session. It’s weird because I remember all the other stuff. I was bloody scared! I know I’ve played with Pink Floyd at this point, and other major artists but I still have this terrible imposter syndrome. I’m basically a West London punk rocker, I shouldn’t really be doing any of this!

NFAA TOM: But you’re “the kid with the riffs!

GP: That’s “riff” again – singular! I only had one! I used it up a long time ago.

It was a band session, and the players were amazing; Jonathan Moffat (drums), Bruce Gaitsch (guitar)¸ Jai Winding (keyboards), Patrick Leonard (keyboards), Bill Bottrell (engineer) – incredible.

And Madonna was so good – she was so ‘on it.’ She sang a guide vocal. She’d give me notes – and they were proper notes. They weren’t like ‘Can you make it more purple?’ She gave me understandable musical things that she wanted me to do. Or not do.

“Like a Prayer” was just me, her, Pat and Bill. I don’t know why I was there. I was thinking because they have the synth on it – that’s all they’d need. There might not have been a plan to put a bass on it. I was in there to simply double some of the verse stuff. I was playing every fourth note or something.

At the end, it was one of those ‘let go nuts’ takes. ‘We’ve got the take we need, let’s just do one more for fun.’ I don’t remember it because I wasn’t taking it seriously. As if I could do that!

Sometime later she invited me down to the mix – I’d come back to California to do the Toy Matinee album and I went down to the studio and she said (in Pratt’s impeccable Madonna Ciccone voice appropriation) ‘Come and sit next to me!’

There was this last really loud play through and I was absolutely stunned. It is an amazing song. The hooks, the arrangement, everything! On that track, there is always something to keep you interested. On that song, you’re always thinking … What now, what now?’

Then the bass thing happened at the end. ‘That sounds like me but it obviously isn’t…’ because that’s way above my pay grade! Pino gets to do that! Tony Levin gets to do that. Mark King gets to do that.

Guy Pratt does not get to do that! Which is why I said to Madonna ‘That is the greatest record you’ve ever made… who played bass on it?’

(Pratt in Madonna mode) ‘You, dummy!!!!!’

NFAA DAVID: I think your Michael Jackson story is more bizarre.

GP: The funniest thing about that story is when I got the call to do it. It was a period of my life that was so insane. I’d done the Toy Matinee record, and I had to leave before the end of making it to fly back to Europe to do a Pink Floyd tour – we went to Moscow and did that amazing gig in Venice. Then I had to fly straight back to Los Angeles to start the Robbie Robertson album (1987). While I was doing Robbie’s album – I did other songs for Madonna such as “Hanky Panky.” One day in the studio I get a call from engineer Bill Bottrell.

“Hey Guy, what are you doing?” I responded ‘Well, I’m working with Robbie.’ Bottrell: “I want you to work on this Michael Jackson song…” I said ‘Okay.’ “Can you be here by six?” Pratt: ‘We don’t usually finish until 6… I’ll have to ask permission!’

So I went to Robbie ‘Listen, is there any chance I can go early tonight?’ Robertson: “Oh why?” Pratt: ‘I’ve been asked to do a Michael Jackson session!’ And Robbie blurted out “What am I supposed to say to that!”

Pratt to Bottrell: ‘Why me Bill?”

Bottrell: “Michael heard ‘Like A Prayer’ and he wants that!”

So I thought ‘Great, he obviously wants full balls-out Octave pedal madness!

I turned up at the studio and Michael had supposedly just left. And they play the track (Pratt sings) ‘What about sunlight…’ And I think to myself ‘Really!? What the hell am I supposed to do with this?’

Luckily Steve Ferrone came in. However was in the worst possible key – Ab! With an Octave pedal that is not good. As a rule, you don’t go below D. In fact, D is the optimum key. Now with modern technology, you can do anything, though I don’t like any of the new Octave pedals unless I’m doing a sub-swell.

For me, it was the Boss OC-2. Boss was actually talking about doing a Guy Pratt edition of the pedal.

NFAA DAVID: Take that Pino!

GP: Yeah! Look I nicked it from him – I make no bones about it. “Tear Your Playhouse Down” and “Give Blood” are the best examples of Pino with the OC -2.

NFAA TOM: When I first heard those tracks, I had no idea they were pedals.

GP: Right because at the time there was no internet. When I first heard “Tear Your Playhouse Down,” I thought ‘it sounds like a synth but it obviously isn’t… but how did I find out it was an Octave pedal? Who do I ask? I didn’t know Pino!’

Do I go up to people and (yell) ‘Tell me tell me’ and leave a trail of bodies all over London? But I did find out…

NFAA TOM: Guy as you are an album artist primarily, we ask all of our guests who work in that format the question “Is the album format still relevant in the age of streaming music?” What say you?

GP: No they are not. Albums were the length they were because Deutsche Grammophon worked out that it was the length of one movement of a symphony. Since that was the format, that’s what record players were made to. So we got used to the album format. Which then became this completely invented format where track listing was everything. From track one on side one, to track one on side two…what is the last track on side two?

Basically, it became a play in two acts. Then the compact disc came along, and that concept was gone. There is no end of side one…there is no end of side two…

Any sort of restriction that is imposed upon you – especially as an artist, is a good thing. That’s why plays are like plays, and films are like films.

It’s good to have these invented laws. Now, there is kind of no point! If you want an album to be 400 songs, it can. That’s why I find it interesting – that amongst a lot of the kids – their preferred format is the EP. Four songs. It’s not the tradition of ‘extended play.’ It’s four songs.

Back in the day, EPs were when artists argued about what was going to be the B side!

NFAA TOM: Or make an extra dollar off additional songs…

GP: Right.

NFAA TOM: Interesting that you mention the term “restriction” because David and I interviewed legendary bassist Jerry Jemmott and asked him that had Jaco Pastorius lived would he have moved on to the extended range bass – five-string, six-string. David and I were convinced that Jaco would have added more strings, yet Jemmott maintains that it is the restrictions of the four-string that made Jaco great.

GP: I don’t think Jaco would have played a six-string.

NFAA DAVID: When you play an extended range – five or six – and I know you’ve tried that – your left hand tends to move horizontally rather vertically.

GP: Yes, that’s what Jack Bruce said – and he preferred five-string. But when you think about it the top note on a Jazz bass…

NFAA DAVID: An Eb!

GP: Yes and it’s a note I actually use in a chord at the end of the song “Saucerful of Secrets” with Nick Mason. The point being, that note, why would you need anything higher than that on a bass guitar?

NFAA DAVID: Well, the idea to me was never doing the ‘diarrhea of the hands’ soloing. My brother-in-law was Ian MacDonald – and when he left Foreigner, we started a band. He bought me a Chapman Stick.

GP: Ah I was about to bring those up!

NFAA DAVID: I wanted to go low, not higher.

GP: Yes, I get that. But with Jaco’s facility, I don’t think he would have gone there. I don’t think Hendrix would have gone beyond the Fender Stratocaster. Look at David Gilmour. No one has done more to expand the horizons of what a guitar can sound like, but it’s still the black Strat.

To me, Jaco’s sound is still so space-aged, modern, and high-tech, and it was just him – what else was he going to do? He already had the future in his fingers!

NFAA DAVID: When it comes to Jaco – yes he was a great player, but it all comes down to his compositions. He was a brilliant composer. Just like Charles Mingus. A great bassist, no doubt. But when you think about Mingus, you think about his compositions.

“Three Views of a Secret,” “Portrait of Tracy,” who, outside of Percy Jones, would have thought of it?

NFAA TOM: According to Anthony Jackson, with whom David studied…the true bass guitar is a six-string. As we discussed this with another Anthony Jackson disciple, your colleague Dave Swift (Later…with Jools Holland). If you place the electric bass next to an electric guitar and an upright bass, clearly the electric bass is a member of the guitar family. Leo Fender, who focused on the marketing aspect of his business, made the bass four strings to appeal to upright players who were weary of hauling the cumbersome doghouse!

GP: I had a Fender six-string bass, but I thought of it more as a baritone guitar. Wasn’t it interesting in The Beatles Get Back film that they had one laying around the studio and that’s what John Lennon picks up to play bass tracks.

NFAA DAVID: Jack Bruce was playing a Fender six-string with Cream! How did he do it?

GP: Right! So let’s go back to the Chapman Stick – which was everywhere in the 1980s. Alphonso Johnson, Tony Levin…and I was thinking ‘Oh my God I’m going to have to learn this thing…’ So I nearly bought one. And I thought I just did those four years in my bedroom; I don’t know if I could go back and do them again. Because that’s what it would take. Then I realized – especially Tony – that he’s only playing two strings on it!

NFAA DAVID: That’s absolutely right! You know what made me decide to get rid of the Stick…aside from how many years it would take to master it? I didn’t want to stand up with the Goddamn thing stuck in my pants!

GP: Exactly! Years back Tony Levin told me that he transcribed Stravinsky’s “Firebird” for the Stick. And I thought ‘We’ll I was never gonna do that!’

NFAA TOM: What’s on Guy Pratt’s bucket list?

GP: The boxes keep getting ticked! There’s only one person I would really like to play with. But… it’s a total Catch-22.

I would love, love, love to do something with Peter Gabriel. But if I do something with Peter Gabriel, that means Tony Levin isn’t doing it – and I always wanted to be kind of… Tony Levin! So I guess I don’t want to play with Peter Gabriel…

More Bass Player interviews are available in an upcoming book: Good Question! Notes From An Artist Interviews… by David C. Gross & Tom Semioli www.NotesFromAnArtist.com

Bass Player Health

Preparing for Performance with Dr. Randy Kertz

Preparing for Performance…

This month we discuss how to prepare for a performance and easy strategies that go a long way.

Dr. Randall Kertz is the author of The Bassist’s Complete Guide to Injury Management, Prevention and Better Health. Click here to get your copy today!

View More Bass Health Articles

Gear Reviews

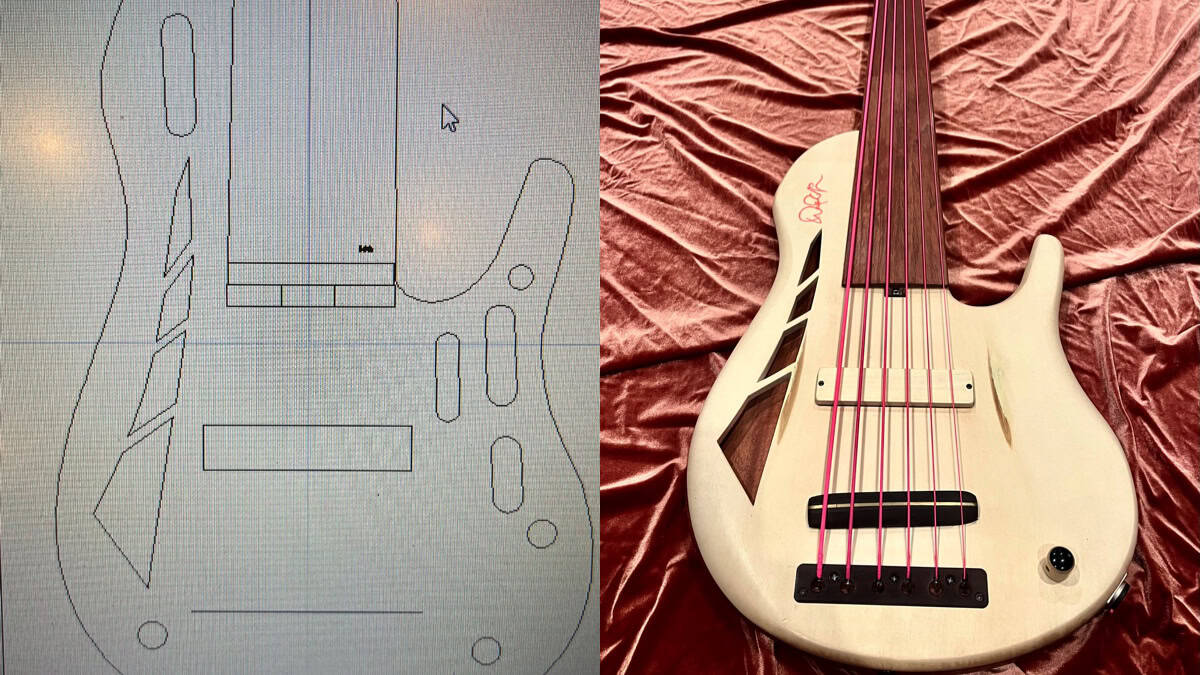

The Frank Brocklehurst 6-String Fretless Bass Build

A few months ago, my Ken Bebensee 6-string fretted bass needed some TLC. You know, the one rocking those Pink Neon strings! I scoured my Connecticut neighborhood for a top-notch luthier and got pointed to Frank Brocklehurst, F Brock Music. He swung by my place, scooped up the bass, and boom, returned it the next day, good as new. Not only that, he showed up with a custom 5-string fretted bass that blew me away. I couldn’t resist asking if he could whip up a 6-string fretless for me.

Alright, let’s break down the process here. We’ve got our raw materials: Mahogany, Maple, and Holly. Fun fact – the Mahogany and Maple have been chilling in the wood vault for a solid 13 years. Frank is serious about his wood; they buy it, stash it away, and keep an eye on it to make sure it’s stable.

First up, they’re tackling the Mahogany. Frank glues it together, then lets it sit for a few days to let everything settle and the glue to fully dry. After that, it’s onto the thickness planer and sander to get it nice and flat for the CNC machine. The CNC machine’s the real star here – it’s gonna carve out the body chambers and volume control cavity like a pro.

While the Mahogany’s doing its thing, Frank goes onto the neck core. Three pieces of quartersawn maple are coming together for this bad boy. Quartersawn means the grain’s going vertical. He is also sneaking in some graphite rods under the fingerboard for stability and to avoid any dead spots. The truss rod is going to be two-way adjustable, and the CNC machine’s doing its magic to make sure everything’s just right.

Now, onto the design phase. Frank uses CAD software to plan out the body shape, neck pocket, chambering, and those cool f-holes. I had this idea for trapezoid F-holes, just to do something different. The CAD software also helps us map out the neck shape, graphite channels, and truss-rod channel with pinpoint accuracy.

Once everything’s planned out, it’s CNC time again. Frank cuts out the body outline, neck pocket, and the trapezoid F-holes. Then it’s a mix of hand sanding and power tools to get that neck just how we like it. Oh, and those f holes? We’re going for trapezoids of different sizes – gotta keep things interesting.

Next step: gluing that neck into the pocket with some old-school hide glue. It’s got great tonal transfer and can be taken apart later if needed. Then it’s onto hand-carving that neck-body transition.

For the custom-made bridge, Frank uses brass for definition and Ebony for tonal transfer and that warm, woody sound.

BTW, for tunes, Frank went with Hipshot Ultralights with a D Tuner on the low B. This way I can drop to a low A which is a wonderful tone particularly if you are doing any demolition around your house!

Now it’s time for the side dots. Typically, on most basses, these dots sit right in the middle of the frets. But with this bass, they’re placed around the 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, 9th, and 12th frets.

Frank’s got his pickup hookup. Since the pickup he was building wasn’t ready, he popped in a Nordstrand blade to give it a whirl.

It sounded good, but I was itching for that single-coil vibe! And speaking of pickups, Frank showed me the Holly cover he was cutting to match, along with all the pink wire – talk about attention to detail!

A couple of things, while it is important for me to go passive, it is equally important for me to just go with a volume knob. Tone knobs are really just low-pass filters and the less in the way of a pure sound for me, the better.

Finally, it’s string time! As usual, I went for the DR Pink Neon strings. Hey, I even have matching pink Cons…Both low tops and high!

Once we’ve got everything tuned up and settled, we’ll give it a day or two and then tweak that truss rod as needed. And voila, we’ve got ourselves a custom-made bass ready to rock and roll.

I want to thank Frank Brocklehurst for creating this 6 string beast for me.

Latest

This Week’s Top 10 Basses on Instagram

Check out our top 10 favorite basses on Instagram this week…

Click to follow Bass Musician on Instagram @bassmusicianmag

FEATURED @adamovicbasses @loritabassworks @hiltonguitars @colibriguitars @sterlingbymusicman @anacondabasses @dmarkguitars @fantabass.it @alpherinstruments @vb_custom_travel_guitars